Government Efforts to Negotiate Drug Price Reductions Will Likely Do More Harm Than Good

Medicare’s new authority to essentially force drugmakers to reduce prices will stifle innovation and may end up costing some seniors more for medications

By Douglas Holtz-Eakin

Using the enormous power of the state to reduce drug prices is not a new idea; neither is the inevitable conclusion that ratcheting down the cost of drugs by government diktat is unlikely to provide hoped-for savings. For instance, in January 2004, as the then-director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), I wrote a letter to the majority leader of the U.S. Senate, saying:

At your request, CBO has examined the effect of striking the “noninterference” provision … of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. That section bars the Secretary of Health and Human Services from interfering with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and sponsors of prescription drug plans, or from requiring a particular formulary or price structure for covered Part D drugs.

We estimate that striking that provision would have a negligible effect on federal spending because CBO estimates that substantial savings will be obtained by the private plans and that the Secretary would not be able to negotiate prices that further reduce federal spending to a significant degree. (Emphasis added.)

Nevertheless, the recent news has been full of positive coverage of the Biden administration’s selection of 10 popular drugs for the new “negotiation” regime enacted as part of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The idea is that Medicare will negotiate with the makers of these medications to dramatically reduce the cost the government pays. The new prices for the first batch of drugs will take effect in 2026. Medicare will choose a different 15 drugs for 2027 and again for 2028, and 20 each year after that through 2035. CBO estimates these total savings of $102 billion over 10 years.

As the letter above indicates, in 2004, the CBO said negotiation would do nothing to save federal dollars. Now, negotiation is said to save over $100 billion. This raises three important questions: What changed CBO’s calculus? Will the IRA’s drug price “negotiation” scheme actually save federal dollars? Even if it works, are these provisions a good idea? Let’s think about each question in turn.

Did the CBO simply change its thinking on the effectiveness of the government’s negotiating power vis-a-vis the private sector? No. Since 2004, CBO has repeatedly pointed out that the Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary has no particular negotiating advantage over private drug plans. The plans already have millions of customers as an enticement for drug companies to offer lower prices. What’s more, these plans can use formularies (a list of drugs available under a specific plan) to favor one drug over another—something the HHS secretary cannot do. Simply saying “go negotiate” does not empower the secretary in any way.

That being said, the IRA is not actually about facilitating negotiation in any conventional sense of that word. The law begins by imposing price controls, establishing a “maximum fair price” (MFP) for each of the 10 drugs, which can be no higher than 40%–75% of the average non-federal price (depending on how long it has been on the market) but can be negotiated lower. That is a price control, plain and simple.

Price controls have a long history of failure. The most prominent example is rent control. Where tried, rent controls have undercut the incentives to build more housing and to maintain and upgrade existing housing. Rent controls exacerbate housing shortages and, ironically, place upward pressure on rents, hurting the very people—in this case, renters with low or moderate incomes—they were designed to help.

Even some advocates acknowledge the IRA has the same problem. “The idea that curbs on drug pricing will stifle innovation has long been the pharmaceutical industry’s go-to argument, wrote the KFF’s executive vice president for policy, Larry Levitt, in a recent opinion piece for The New York Times. “At some level, the drugmakers might be right: Lower prices mean lower profits, and that will be less attractive to investors. Drug development is a risky business, and the appeal for investors is the big potential payoff fueled by higher prices.”

Price controls are bad enough policy, but the IRA does not stop there. As Levitt notes: “the I.R.A. includes a substantial inducement to bring drugmakers to the negotiating table: a tax of up to 95 percent of a selected drug’s U.S. sales if a company does not comply with the negotiating process. Alternatively, a company can choose not to have its drugs covered by Medicare and Medicaid, though few if any would give up the business.”

It’s important to note that the “substantial inducement” is a tax equal to 95% of the tax-inclusive price. Unscrambling the tax-on-a-tax, this amounts to 1,900% of the tax-exclusive price, or the amount the manufacturer receives when it sells the drug. Having to pay $19 in taxes for each $1 of revenue would put an end to sales of that drug. It is pure fiction to describe this combination of price controls and ruinous taxation as a negotiation, unless your definition of “negotiation” is that one side holds all the cards and the other is essentially powerless.

Nevertheless, there remains the question: Will it work—that is, will the IRA drug pricing regime lower Medicare spending by roughly $100 billion? The reality is that there is precious little evidence on which to base an estimate, so what estimates do exist are very speculative. Also, as a matter of general practice, CBO recognizes the uncertainty and chooses its projections so that they are just as likely to be too large as they are to be too small. So, there is no reason to expect the savings to roll out exactly as estimated.

There are also forces driving prices in both directions. Yes, price controls immediately reduce the MFP to 40%–75% of the average manufacturer’s price, but this cap just creates an incentive for the manufacturer to raise the price as high as possible before a drug enters the IRA regime. This incentive is reinforced by another IRA provision known as the “inflation tax,” which holds that, once the clock starts ticking on a drug, if the price of a drug rises faster than the general rate of inflation, 100% of the revenue from the excess drug price must be paid to Medicare as a rebate. Combined, these two features provide a strong incentive for manufacturers to launch new drugs at as high a price as possible.

The IRA regime may also deter the entry of generic drugs and biosimilars. It is one thing to plan the production and marketing of a competitor drug if the original is still being marketed at its monopoly price. It is quite another to face the possibility of arriving on the market precisely at the moment the price has been slashed by Medicare to below the break-even level. Fewer drugs would lead to less competition, which in turn would lead to higher prices. And, of course, since the MFP applies only within Medicare, manufacturers may attempt to raise prices in the commercial market to recoup at least part of what has been lost in Medicare.

This leads to the final question: Even if the IRA produces some reduced Medicare spending, is it a good idea? The administration certainly wants you to think so. Its fact sheet emphasized: “Up to nine million Medicare enrollees spent $3.4 billion out of their own pockets in 2022 on the 10 drugs that will initially be subject to negotiation.” That sounds impressive. But upon closer scrutiny, this is just $31.48 per month per enrollee, or about two Starbucks lattes a week.

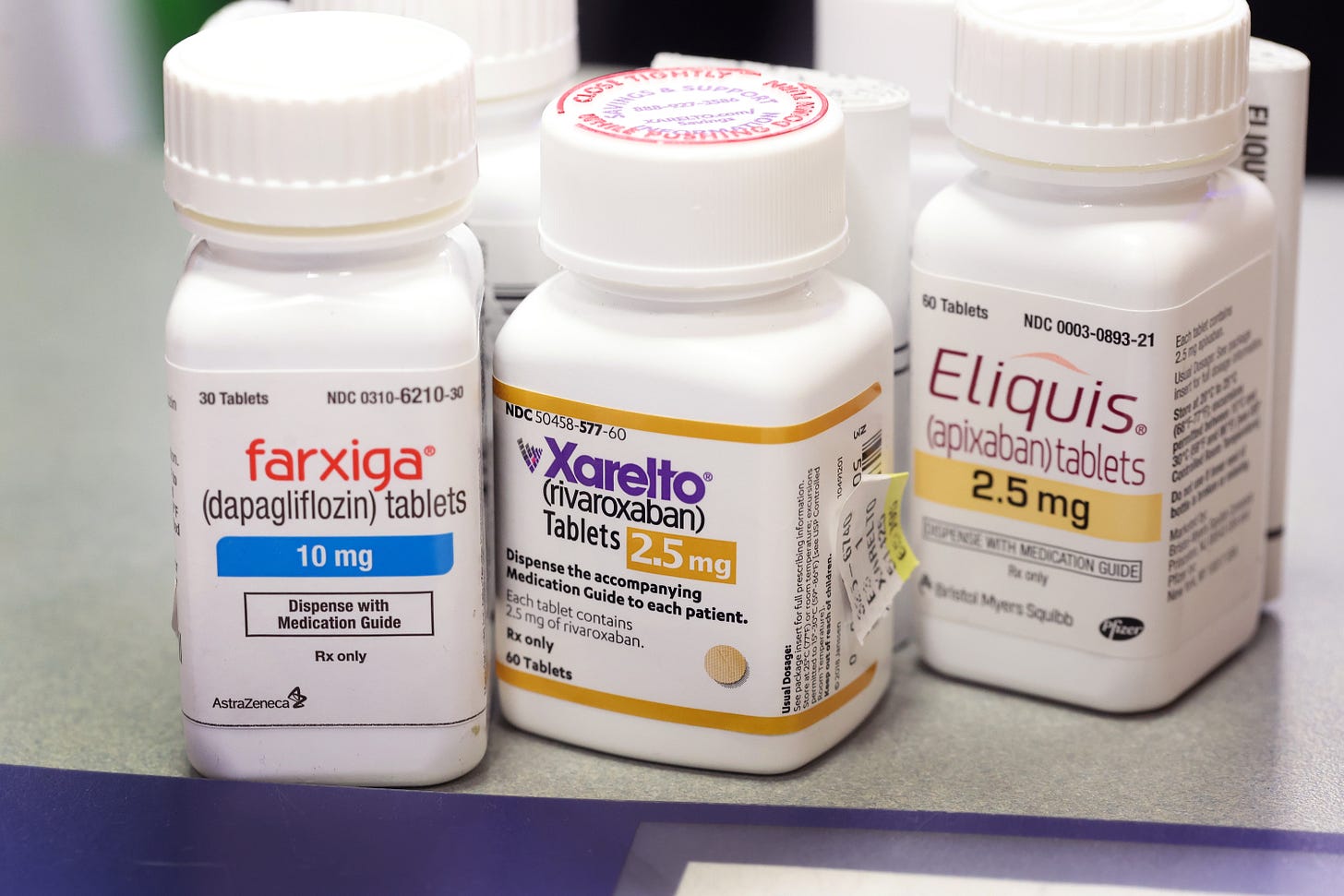

For some seniors, the new law might not save them a dime. Instead, it may mean they end up spending more out of pocket. To see why, consider that on the list of designated drugs is Eliquis, an anticoagulant that treats blood clots. What is even more interesting is that Xarelto, another blood thinner, is on the list, too. These choices seem a little weird: Neither is a particularly expensive drug when measured by cost per dose ($8.50 and $16.40), cost per prescription ($739 and $809), or annual cost per beneficiary ($4,023 and $4,153).

These aren’t the high-priced poster children used to sell the idea of drug negotiation. These are simply moderately priced, widely prescribed modern therapies. They also compete head-to-head for market share among seniors, not just by price but also by paying rebates to private insurance companies for preferred placement on their drug plans’ formularies, where beneficiaries often pay a small co-pay or nothing at all for medications.

What happens as a result of the IRA’s drug price-setting regime? Suppose that the MFP ends up being the same as the old “net price”—the price after manufacturers pay rebates. If so, the plans get this low price automatically and have no particular incentive to continue offering the drug to beneficiaries on a formulary with no co-pay. It could easily be the case that the manufacturers are left unscathed, the plans are made better off, and that the only losers are the beneficiaries who now have greater out-of-pocket costs and, as a result, less access to the therapies.

The IRA is a toxic mix of price controls and extortionary taxation. It may, indeed, save Medicare enough to lower drug plan premiums a bit for each senior. But for some of those same seniors, their out-of-pocket costs may be higher. There will be incentives for drugmakers to raise prices, both inside Medicare as well as in the commercial market. Finally, this new regime may well disincentivize spending on research, leading to less innovation in new drugs and therapies.