Give Private Currency a Chance

One possible solution for inflation is to allow competition among currencies

By Timothy Effrem and Patrick Horan

For well over a year, the U.S. and many other developed countries have felt the pain of high inflation. Rising prices have not only reduced the dollar’s purchasing power, but they have battered stocks, causing people to scramble for other options to preserve their wealth. Cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin, which had been touted as good inflation hedges and have been legitimate havens for people in extreme inflation environments (e.g., Venezuela and Argentina), have also plummeted over the past few months.

The Fed and other central banks are tightening monetary policy to rein in inflation, but can private entrepreneurs improve upon today’s fiat currencies and volatile cryptocurrencies with new innovations?

While it’s highly unlikely that private currencies will supplant government-issued fiat currencies such as the U.S. dollar anytime soon, due to the latter’s widespread usage by the public, policymakers should embrace competition from cryptocurrencies and other private currencies (existing or hypothetical). In an environment that encourages rather than discourages competition, entrepreneurs can more easily experiment and produce currencies that the public wants. Moreover, private currencies can act as a form of discipline on central banks to keep inflation low lest they lose their currencies’ users to private competitors.

Private Money Can Work

The question of whether private actors can produce better money than governments is not new. From the 18th century to the early 20th century, many countries experimented with “free banking” regimes where private banks would issue their own currencies or bank notes, which were redeemable for gold or silver. During the “Great Inflation” of the 1970s, the Nobel Prize winner Friedrich Hayek proposed that private issuers be allowed to issue their own paper money, arguing that they would be less likely to overproduce their currencies than central banks and thus cause less inflation. Many economists and other observers have cited Hayek’s proposal as a theoretical forerunner to bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

Around the time Hayek was writing about theoretical monetary reforms, Dr. Ralph Borsodi used his own money to launch a real-world private currency experiment in the small town of Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1972. The currency was called “the constant” because it was worth a constant basket of 30 globally traded commodities, including gold, silver, oil, wheat, wool and sugar. Since redeeming constants for all 30 commodities would be impractical, constants could be converted into silver medallions.

Arbitrage International, a nonprofit corporation set up by Borsodi, issued constants in exchange for dollars and then invested those dollars in high-yield government bonds. Two local banks cooperated with Borsodi’s experiment and allowed townspeople to open savings and checking accounts denominated in constants. Around 180 of Exeter’s 8,900 citizens opened such accounts. Some local merchants accepted payment in constants, and the Exeter police even accepted constants as payments for parking violations!

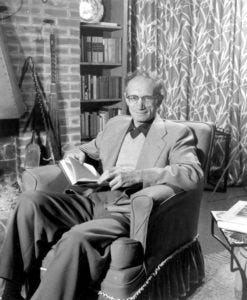

Private currency pioneer: Ralph Borsodi, inventor of the constant. Image Credit: State Archives of Florida/Wikimedia Commons

Because of Borsodi’s fading health, as well as concern from the Securities and Exchange Commission that the endeavor might not have been legal, the constant experiment ended 18 months after its launch. At the project’s conclusion, people redeemed their constants for dollars. True to their name, constants maintained their value against the basket of goods behind them and increased their value against the U.S. dollar, so constant users earned a dollar-denominated profit.

Although the constant project was short-lived, it was successful in the sense that it proved an alternative, inflation-proof currency could exist alongside the U.S. dollar and that consumers found the currency useful. Admittedly, the constant’s use was not widespread, but its relative popularity suggests that perhaps its use could have spread to neighboring areas over time. Moreover, the worldwide spread of bitcoin shows that a private currency can gain trust among users internationally, even when its creator is unknown.

Constants vs. Crypto

Borsodi’s constant has clear parallels with today’s cryptocurrencies. All are examples of privately produced rather than government-issued currencies. That said, cryptocurrencies vary widely in terms of how they are generated and issued. Many people chose to invest in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies because they were interested in earning a large positive rate of return. By contrast, the constant was intended to preserve rather than increase purchasing power.

Cryptocurrencies have helped users escape high inflation in developing countries and avoid surveillance from authoritarian leaders. Yet some have questioned the viability of these currencies because of recent trends in cryptocurrency prices and the collapse of certain stablecoins, cryptocurrencies whose prices are supposed to be pegged to other assets, such as the U.S. dollar.

We do not know if there will be widespread adoption of private currencies like cryptocurrencies. But we do know that markets are constantly evolving, if not always successfully, to satisfy consumers’ preferences. For example, a future entrepreneur may see shortcomings of both existing cryptocurrencies and fiat currencies and attempt to create a modern version of Borsodi’s constant or new digital coins, which could potentially increase in value but be less volatile than existing coins such as bitcoin. If users came to prefer such alternatives for entirely legitimate reasons, those currencies should be allowed to thrive.

Possible Government Actions

Governments can and should establish a framework where private currencies can exist on an even playing field with fiat currencies, so long as their issuers are law-abiding. One might say that governments already do this by allowing the existence of private currencies, but in the world’s two most populous countries, crypto faces great hostility. Since 2009, China has banned, relegalized and rebanned cryptocurrencies more than a dozen times. After previously banning cryptocurrencies, India now allows them but has instituted a prohibitively high 30% tax on crypto transactions.

U.S. crypto policy is far less draconian, but as the Cato Institute’s Nicholas Anthony points out, there is still room for reform. U.S. legal tender laws are ambiguous about whether it is legal to accept cryptocurrencies for payments. Anti-counterfeiting law prohibits coins that have a “resemblance or similitude” to U.S. coins, but it does not clarify what resemblance a digital coin would need to have to be considered counterfeit. Such laws could easily be modified to remove this ambiguity.

Anthony also argues that existing capital gains taxes discourage using cryptocurrencies to buy goods and services. One way to rectify this problem would be to terminate or scale back capital gains taxes on transactions when cryptocurrencies are used to purchase goods and services, but keep such taxes in place when they are sold simply as a means of earning cash.

More generally, when policy is opaque, people are less likely to take risks that may otherwise be profitable for fear of breaking the law. Borsodi’s project ended in part because of regulators cracking down. U.S. policymakers should work to make sure entrepreneurs are confident they understand the regulatory landscape and are not likely to be impeded by bureaucrats after launching their ventures.

Taming the ‘Wild West’

Some critics argue that promoting private currencies is akin to encouraging a “Wild West” environment where people can lose their wealth should the currencies fail. Indeed, some policymakers have compared modern-day private currencies to the bank notes issued by the “wildcat” banks of the mid-19th century. In their view, unscrupulous banks issued their own bank notes, which they falsely claimed were backed by gold or silver, to scam customers. They were able to do so because there was insufficient regulation during this “free banking” era.

As economist George Selgin shows through a closer look at the historical record, this view is largely false. Only a minority of banks were “free” (i.e., allowed to operate without a bank charter), and free banks were still subject to regulations. For example, banks were not allowed to establish multiple branches and needed specific collateral, including government bonds, to issue notes. Most free banks were also not wildcats, and most states with free banking saw no instances of fraud.

Wildcat banking occurred in only five states. Of those, Michigan saw the worst cases, but this had more to do with a poorly designed law that effectively encouraged dishonest bankers, who otherwise would not have survived market discipline, to enter the market. In the other four states, bank failures likely had more to do with external developments than fraud. For example, many Wisconsin free banks failed because of their investment in Southern state government bonds, whose values fell at the onset of the Civil War.

In other words, wildcat banking was the exception, not the rule, and should not be used as an argument against private currencies today. Policymakers should not be complacent about the possibility of fraud, but a regulatory framework that promotes competition and innovation should lead to less fraud because dishonest issuers would not last long in the marketplace; consumers would only turn to private currencies if they found a benefit.

Since private currencies compete with fiat currencies, governments would naturally have a strong incentive to treat such currencies with skepticism and, in the case of more authoritarian countries, antagonism. This is why governments should explicitly state either in law or in regulatory code that private firms are free to issue their own currencies without onerous regulation or taxation as long as they are fully law-abiding.

Moreover, governments can also benefit from private competition. First, taxes on speculative capital gains from the sale of cryptocurrencies are a source of revenue for governments. Additionally, central banks have more incentive to produce a sound monetary policy if there are private alternatives to fiat currency with low to no inflation. While people in the developed world have largely gotten used to low inflation (with the recent surge being an exception), we should not be complacent about the dangers of high inflation.

Although policymakers tend to treat money as a good that only the government can provide, private issuers should at least be given a fighting chance to compete in this space. Only by permitting and encouraging innovation can we see if the private sector is able to offer better money than the government.