Finding Freedom in “Walden”

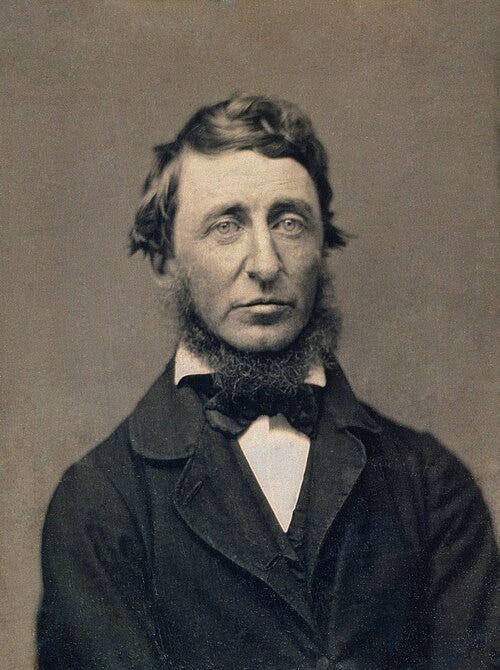

180 years after Henry David Thoreau moved to Walden Pond, we can learn a lot from his ideals, even when he didn’t live them out perfectly

Years ago, I overheard a college classmate joke about wanting to go to Concord, Massachusetts, and visit Walden Pond so she could spit in it.

Her contempt for Henry David Thoreau’s classic book “Walden: Life in the Woods” caught me by surprise, but because I trusted her literary tastes, I decided I could set the book aside, having only skimmed a portion of it in high school. It turns out that she was far from alone in her low opinion of the book. The negative reviews for Walden on Goodreads excoriate Thoreau for being a “squatter,” a “moocher” and a “self-righteous hippie” whose few useful ideas are drowned in an ocean of pretentious sentences. Or as Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker a decade ago, “The real Thoreau was, in the fullest sense of the word, self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control, adamant that he required nothing beyond himself.”

But in 2024 I came across one quote by the man that grabbed my attention: “The cost of a thing is the amount of … life which is required to be exchanged for it.” That insight struck me as very true, and I wondered if Walden held more wisdom than I suspected. So I finally decided to sit down and read Walden… Thoreau-ly.

To be honest, I can understand my college classmate’s joke about desecrating Thoreau’s hallowed waters and the invective in the book’s negative reviews. Thoreau’s smug superiority often made me roll my eyes. And sometimes I had to pause the audiobook to take a break from his over-detailed self-congratulations.

But the author’s shortcomings are less than half the story. I also realized why Thoreau’s writing has stood the test of time and inspired so many people. He moved to Walden Pond just over 180 years ago, on Independence Day in 1845, and his book reads like a personal Declaration of Independence. Written in an age witnessing the dawn of everything from mass industrialization to railroads to the telegraph, you can read Thoreau’s “Walden” as one American’s attempt to break free from the uncompromising march of modernity. It’s a freedom many of us are still searching for today.

And while Thoreau might ultimately have fallen short of the ideals he set forth in 1845, that could be said for many provocative thinkers and writers. I don’t think we need him to rise to all those ideals, though. We read “Walden” today not to admire how Thoreau could survive out in the wilderness or live alone in the woods without losing his mind. We read “Walden” because Thoreau asked questions about how we live and how we should live, questions that resonate nearly two centuries later. Despite nearly two centuries of dramatic social change and technological progress, human nature today is in many ways very much the same as it was when he built his cabin at Walden.

And so, there are still lessons we can take from this very American classic. Here are just a few:

Debt and Freedom

During one fishing trip, Thoreau was caught in a massive thunderstorm. He found shelter in the small home of an Irish immigrant named John Field. The farmer talked about his financial situation, earning $10 for preparing one acre of land for planting, but spending all of that money on rent, tea, coffee and meat. Beneath a leaky roof, Thoreau urged Field to simplify.

“I tried to help him with my experience, telling him … that I lived in a tight, light, and clean house, which hardly cost more than the annual rent of such a ruin as his commonly amounts to,” he wrote. “And how, if he chose, he might in a month or two build himself a palace of his own.”

This anecdote reveals Thoreau at his most insufferable ― like a hitchhiker who lectures the driver who’s picked him up about his car payments. Thoreau detested debt and harshly judged anyone who had accumulated it. He observed that most farmers in his region “have been toiling 20, 30 or 40 years” to pay off their mortgages. He believed “many a man is harassed to death to pay the rent of a larger and more luxurious box” than what is truly needed. He was serious when he used the word “box,” once suggesting that people could take up residence in recycled wooden toolboxes like railroad workers used to store equipment. They might not have a fireplace, but at least they’d be debt-free.

But maybe more people should have listened to him. Americans seem addicted to debt. In 1845, the United States government held about $16 million in debt. Today, adjusted for inflation, that would be about $540 million. The national debt is more than 60,000 times that much today. On top of this, Americans currently have $18 trillion in consumer debt. Sure, that debt has allowed us to buy a lot more stuff, including things we need. But judging from the popularity of decluttering books and documentaries, many of us clearly think we have way too many things we don’t need.

In this respect, Thoreau reminds me of Dave Ramsey, the author and radio host who coaches people on “financial freedom,” who often says that “We buy things we don’t want with money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like.” I’m not advocating the same sort of spartan lifestyle that Thoreau celebrated, but he was onto something. “The only true America”—the only true freedom—“is that country where you are at liberty to pursue such a mode of life as may enable you to do without these.”

Becoming the Tools of Our Tech

Thoreau relished in the ability to live without conveniences that others viewed as necessities. In her New Yorker piece about Thoreau, Schulz called “Walden” “the original cabin porn: a fantasy about rustic life divorced from the reality of living in the woods.” But you also could consider “Walden” the first “stunt memoir,” the genre in which an author takes on an unusual, temporary challenge, whether that’s living by every injunction in the Bible, cooking every recipe in Julia Child’s most famous cookbook, or living without the internet or electricity.

Like the authors of these books, Thoreau did not want to escape technological progress, but its unintended side effects. Specifically, Thoreau argued that technological progress creates as many, or more, onerous obligations as it does benefits. “Men have become the tools of their tools,” he wrote. A farmer became rooted in place, losing the ability to freely wander, and perhaps the ability to freely wonder, too. A homeowner must spend time on maintaining their home, time that could have been spent on something more fulfilling. Inventions “make this low state comfortable and that higher state to be forgotten.”

This seems especially appropriate for many inventions of our time, each with its own drawback. Email makes us slaves to the inbox, where hundreds of messages pile up each day. Social media makes it easier to connect with people across the country than with someone sitting across the table. Smartphones let app developers pester us with notifications that disengage us from the world around us. Given that these distractions often serve the purpose of luring our attention in order to sell us something, they really can make us the tools of our devices.

The side effects of these technologies are more than personal headaches and distractions, though. The sociologist Matthew Facciani, author of a new book about misinformation, recently told me that many of the challenges we face with false information and distrust in institutions stems from disconnection. “We’ve gotten away from connecting with people on a local level in person,” he told me. Perhaps rather than sharing a fact check on social media, we should go bowling with someone who might disagree with us.

Of course, each person can make their own choices about the tradeoffs and set their own boundaries. The same smartphone that delivers notifications to you also allows you to turn notifications off. But “Walden” reminds us to actually do that rather than rush to buy new technology without thinking about it.

“Resistance is Futile”

Another feature that “Walden” and today’s stunt memoirs have in common is the eventual return to normal life. After two years, Thoreau left his cabin by Walden Pond and spent many of his remaining years working in his father’s pencil factory, although he also published his book about life in the woods. It reminds me of those who write books about swearing off social media and then return to social media to post about their books.

You could look at this as hypocrisy, and you would not necessarily be wrong. Thoreau looked down at those who read newspapers for gossip, but he frequently “strolled to the village to hear some of the gossip which is incessantly going on there.” He eventually leaves Walden Pond because he had “several more lives to live and could not spare any more time for that one.” Was he living a double life all along?

But another way of seeing the ending in “Walden” (as well as in the stunt books) is to think of it as the closing chapter of what Joseph Campbell famously called the Hero’s Journey, when a mythical hero returns from the journey with the valuable lessons learned along the way. The hero doesn’t have to be perfect, nor does the entire story need to be true, for us to receive those gifts.

In Thoreau’s case, his falling short of his ideals and his eventual return from the woods teaches us how challenging it is to live simply in a complicated world. You can build a house in the wilderness and even live there, but you can’t stop the world from coming to your door. You can go offline, but you might need to log on again for everyday tasks like paying bills or registering kids for school without waiting in traffic. Even the most devoted luddite may be forced to get a smartphone if landline phones and flip phones are no longer available. As the Borg in Star Trek’s say, “Resistance is futile.”

In Thoreau’s words, “Wherever a man goes, men will pursue and paw him with their dirty institutions, and, if they can, constrain him to belong to their desperate odd-fellow society.” Rather than a hypocrite, perhaps Thoreau was someone who ran from modern vices and eventually gave up. One lesson we learn from him, however, is that \ it is worth trying to escape.

Finding Walden Today

When I decided to dust off this unfinished article and send it to Discourse Magazine, I wondered whether I needed to make a pilgrimage to Walden Pond to bring my experience with this book full circle. I glanced at directions on Google Maps. It’s a 14-hour drive.

But then I remembered what Thoreau wrote about the economics of travel: He could walk 30 miles in less time than it would take to earn the money for a train ticket. Transportation is much more affordable today, relative to wages, but his point still rings true. Often we are “spending of the best part of … life earning money” to enjoy something we could get more simply.

Instead of trekking to Walden, I went for long, moonlit walks in my neighborhood. My wife and I hiked around a millpond in a nearby state park. I packed my phone away for hours on a family outing to a lake. I stayed later than usual at my writing group meeting, munching M&Ms and talking with friends about our writing projects.

It turned out that I didn’t have to travel 900 miles to find Walden; it was only a quick walk or car ride from my house.