Fair Witnesses of the Digital World

Fighting disinformation inevitably turns into producing it

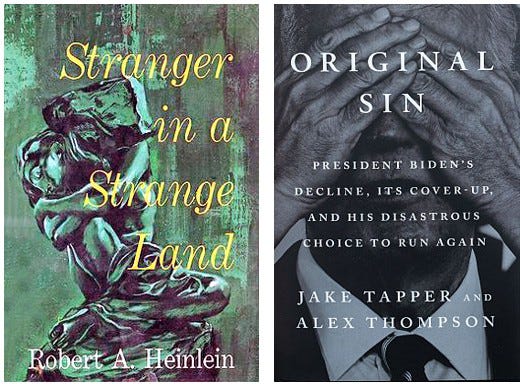

Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s widely discussed new book, “Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again,” has revived the disinformation debate in the U.S. It turned out that the largest and nearly most successful disinformation campaign, thwarted only by Joe Biden’s disastrous presidential debate performance, was conducted in conjunction with the media—those who were supposed to be fighting disinformation. This is hardly surprising: The very concept of disinformation has throughout its history turned all involved into political operatives, and led them to produce disinformation despite claiming the opposite.

Unfair Witnesses of the Internet

In his 1961 sci-fi novel “Stranger in a Strange Land,” Robert A. Heinlein invented the profession of “fair witnesses”—licensed observers that provided objective and precise testimony of events. Called upon for legal disputes and contracts, fair witnesses reported what they observed. When Anne, a fair witness, was asked what color the house on the hilltop was painted, she looked up and said: “It’s white on this side.” She was trained never to assume and could not testify about the color on the sides she could not see. Essentially, fair witnesses like Anne were notaries of truth. Observing reality accurately was only part of their job; the other part was certifying reality as publicly sanctioned and accepted facts.

Heinlein imagined an ideal. In real life, both roles—observing reality and certifying it—have been embodied, though never ideally, by priests, judges, notaries and journalists. The internet, however, has formed a new reality, and new fair witnesses have not taken long to emerge. Disinformation researchers and fact-checkers have stepped in to certify digital reality.

The issue with this latest embodiment of “fair witnesses” was that, from the very beginning, they were recruited for political purposes in the context of political struggle. It’s hard to believe now, but 10 years ago, fake news wasn’t a major concern of the public, and the word “disinformation” wasn’t even commonly known. Hillary Clinton’s shocking loss to Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential race changed everything. To progressive elites, the only acceptable reason to explain Trump’s win was foreign meddling, and so blaming foreign info-ops became a psychological refuge and soon a political strategy.

Digital platforms suddenly found themselves responsible for spreading fake news and divisive information on behalf of the enemy. To avoid regulatory retaliation, they introduced moderation and began contracting third-party expert organizations to sift through online content. There was no other reason for the industry of combating fake news and disinformation to emerge: It was a politically motivated initiative by digital platforms seeking to demonstrate compliance with elites and the bureaucracy.

Because of this, the new industry of content control simply could not recruit experts other than those aligned with progressive elites. In Heinlein’s novel, fair witnesses wore white robes to symbolize purity and impartiality. In our nonfiction story, political circumstances required fact-checkers and disinformation researchers to wear blue.

The Fallouts of Combating Disinformation

The overlapping interests of elites, bureaucracy, digital platforms, old media, academia and nonprofits created ideal conditions for the industry and the profession of “digital reality certification” to grow. The conditions also favored both bureaucratic and regulatory capture. To justify the demand for its services, the industry broadened the scope of its application and the subjects it aimed to regulate. Starting with combating foreign disinformation, it quickly expanded to fighting false information from the domestic alt-right, COVID misinformation and, eventually, any information challenging dominant narratives.

The extensive growth affected not only practice but also theory. The concept of disinformation was soon joined by misinformation, misleading information and eventually malinformation—information that is essentially true but deemed harmful if made available to the public. For example, malinformation could be a post from a person experiencing vaccine side effects, because when shared publicly, such a post could discourage vaccination. Imagine a fair witness who says, “Yes, the house is white on this side, but people had better not know about it, as it might mislead them.”

The privilege of telling people right from wrong, especially when backed by urgent political demands and enormous platforms’ power, is highly seductive. The certification of reality inevitably brings a sense of self-entitlement, all too familiar, for example, to journalists. It is essentially authoritarian—it positions reality certifiers as shepherds over the flocks of people. The gullibility of the public becomes even necessary to justify the authority of guidance and protection.

The Church sought to combat this delusion of authority in its priests, isolating it as a specific sin of “spiritual pride”—the sense of self-righteousness and arrogance that could lead to the misuse of spiritual authority. Traditional journalism also attempted to mitigate this professional risk, developing industry standards centered on objectivity and impartiality. Judges and notaries have their respective professional codes, too. But standards of impartiality are hard to employ when the demand is inherently political.

Fact-Checking vs. Fighting Disinformation

Political engagement, however, affected fact-checking and the combating of disinformation in different ways. Fact-checkers, to their credit, developed professional codes. Yet the issue with fact-checking lies not in the quality of the procedure, but in the choice of what to fact-check. A thought experiment: Which of the following would be fact-checked vigorously—Biden’s statement that vaccines prevent infection, or Trump’s implication that disinfectants kill viruses? The former is false but “socially beneficial,” while the latter is correct but dangerous because people could listen to Trump and inject themselves with disinfectant (assuming that people are stupid, as the “shepherd-flock” dynamic presupposes).

Aside from fact-checking, combating disinformation has its additional pitfalls: It tends to turn into propaganda and censorship. The very concept of disinformation, borrowed from the Soviets, actually deals not with truth or falsehood, but with sanctioned versus unsanctioned narratives. Once accepted, the concept is also very agonistic: It sees the area of regulation as a battlefield, turning opponents into enemies. This framing converts “researchers” into political operatives. It’s inherent to this occupation, and hardly anyone involved has managed to escape it.

Lastly, due to its warfare nature, combating disinformation tends to evolve into producing disinformation. The most massive and effective disinformation campaigns, such as stories involving Hunter Biden’s laptop or President Biden’s mental “sharpness,” did not come from those whom the disinformation research industry fought against, but from those who curated and sponsored this industry. While most researchers and fact-checkers had nothing to do with it, their association with the machinery that facilitated such a massive cover-up has ultimately become a liability.

The Lessons of Fighting Disinformation

Now, the threat of retaliation looms over those who were involved in combating disinformation, and they’re about to find out whether cancel culture is a real thing or just a moral panic. Original cancel culture relied mostly on corporate HR, but what may emerge instead could resemble something more like McCarthyism, with its enforcement power resting not (only) on corporations but also on official authorities and courts.

However, for those eager to start a witch hunt against former disinformation experts, it’s worth remembering that political tides tend to change quickly. Yes, if bureaucrats were involved in censorship, it might constitute a violation of the First Amendment, and there should be respective consequences. But as for disinformation experts, they pay with their reputations. Prosecuting experts does not solve any problems but instead fuels polarization even further. And the stronger the polarization, the more drastic the next shift in political tides.

Having faced both growth and crisis, the industry of checking online speech may have already learned its risks and limits. Fact-checkers are already distancing themselves from anti-disinformation activity, emphasizing the impartiality of their rigorous standards. Like priests, judges, notaries and journalists before them, fact-checkers have a chance to evolve into a profession suited to the new conditions. Perhaps the digital environment, with its emancipated authorship and the ambiguity of truth, can indeed offer a sustainable niche for fact-checking as a media service.

The Issue Remains: How To Deal with Free Speech ‘Falsifying’ Reality?

In the meantime, the internet remains a source of frustration, with its overload of fake news. But it’s the overload itself that likely hurts more than the very existence of fake news. The old era of broadcasting, when Walter Cronkite would say “And that’s the way it is”—and it was that way—is long gone. What frustrates people the most is the need to decide for themselves whom to trust and, especially, the apparent inability of others to figure out whom to trust.

In other words, everyone thinks others are too vulnerable to internet lies and manipulation. This is known as the “third-person effect”: Others fall for stupid ideas and fakes, but not me—I know that the internet is unreliable. But if everyone thinks this way, it means everyone is already aware that the internet is dubious.

The “third-person effect”—the alleged inability of “others” to deal with fake news and manipulation—is often presented as a motive and justification for harsher control of online speech. But it’s already the third decade of social media, and people are well acquainted with the quality of online information. The frustration it causes is more like a fever—something any organism experiences while developing immunity. Painful as it is, it’s a good symptom. Immunity, not the suppression of “wrong speech,” is the key.

So, combating disinformation is a political enterprise. Fact-checking can be a viable business, part of the new ecosystem, once it accepts that it produces content, not truth (something akin to explanatory journalism). But the true solution to the issue of fake news and disinformation is not the suppression of sources. In an environment of free access, suppression only strengthens “wrong speech.” Contrarian views will find a way anyway; when suppressed, they gain greater momentum, as Trump’s return has proven. To eradicate “wrong speech”—an inherently organic feature of new media—one would need to establish total digital control. It’s hard to say if that’s even feasible. But if it is, the result will dwarf the gloomiest cyberpunk anti-utopia—in the interests of “protecting democracy.”

The real solution lies in developing tolerance for the ambiguity of truth—alas, typical of digital culture. The abundance and obscurity of sources, manipulative attempts and fake news are all organic features of this environment—features people must adapt to, just as they did in all previous eras of media change. Attempts to suppress disinformation cause more harm than what’s being suppressed; immunity does not.