Executive Orders Aren’t Always the Best Tool

By Eileen Norcross and Kofi Ampaabeng

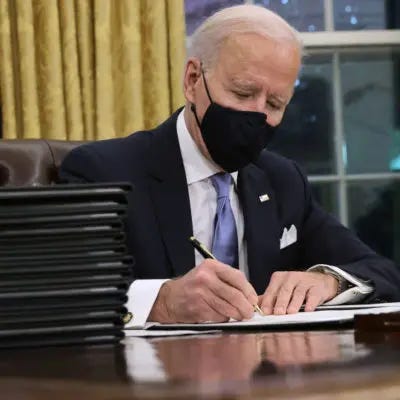

In the first eight days of his presidency, Joe Biden signed more than two dozen executive orders—a record number issued by a president in his first week in office. Covering everything from COVID response to immigration, raising the federal minimum wage, student loan relief and climate change, Biden’s actions immediately undid 30 EOs signed by President Donald Trump. The ink was flowing so fast that The New York Times advised in its editorial pages, “Ease Up on the Executive Actions, Joe.”

Executive orders are not only an effective way to turn the presidential page and send strong signals right out of the gate, they also reward the voter base as supporters see policies quickly implemented or eliminated. “Stroke of the pen. Law of the land. Kinda cool,” quipped Paul Begala, aide to President Bill Clinton, in 1998. Phillip Cooper, in his book By Order of the President: The Use and Abuse of Executive Direct Action, identifies multiple motivations for presidents to issue EOs: war and disaster response (WWI, WWII, 9/11, Hurricane Katrina); international or domestic conflict (Iran sanctions, response to labor strikes); establishment of commissions; advancement of social change against entrenched opposition (President Harry Truman’s desegregation of the military). But while EOs have their place, using them as a workaround to the constitutionally specified legislative process—as has often been done—has led to institutional, political and other problems.

What Is an EO?

Executive orders are issued by presidents to provide guidance and instructions to federal agencies. They are legally binding unless they conflict with statutes or the Constitution. In addition to EOs, presidents may use other channels to unilaterally impose rules on agencies, including executive memoranda and guidance documents.

EOs are tactical—a way around legislative impasses and sometimes a calculated dare aimed at an obstructionist Congress. As documented by several legal scholars, President Barack Obama issued EOs and other presidential directives to advance policy after Democrats lost their majority in Congress and Republicans blocked his legislative initiatives, including immigration reform and funding of the Affordable Care Act. Similarly, President George W. Bush, frustrated with the inaction of Congress, issued several executive orders to achieve his administration’s goals on immigration reform and energy policy.

The Biden administration had issued 32 EOs as of Feb. 24. Of these, a number were not just administrative directives to agencies but were meant to advance policy goals. But are EOs really the best way to advance a policy agenda? They are fleeting—easy to make and easy to undo. They are limited in scope and subject to congressional and court challenge. And they are not necessarily a sure thing in the hands of agency officials: EOs may run into agency roadblocks. Joshua Kennedy, a scholar on presidential power, finds that very few orders result in the promulgation of a rule by an agency. Between 1989 and 2011, out of 4,120 orders issued by presidents, only 371 of them resulted in rules being issued by the respective agencies. Factors such as the ideological views of agency leaders, specificity of the directive and staff competency affect EO implementation.

Furthermore, while they may help to demonstrate executive leadership in advancing a policy agenda, they may also increase partisanship. In addition, they usurp the power of the people’s representatives to be involved in policymaking.

History

The American Presidency Project keeps track of executive orders. With a few exceptions, EOs were rarely used until the early 20th century, with presidents issuing an average of two to three dozen each year after the Civil War. Teddy Roosevelt broke that record by an order of magnitude, issuing a total of 1,081 during his presidency. Woodrow Wilson, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover kept a similar pace, only to be outdone by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s record-breaking 3,721 EOs. It was at the end of FDR’s first term that the government began to track EOs in the Federal Register.

The use of EOs began to level off slowly under Dwight D. Eisenhower (484), dropping to a low of 166 under George H.W. Bush. Trump finished his term with 220 EOs, fewer than Jimmy Carter (320), Ronald Reagan (381), Bill Clinton (364), George W. Bush (291) and Barack Obama (276). But volume only says so much. Content counts. In terms of importance, EOs range from symbolic to significant. With far-reaching impacts on businesses, governments and individuals, they can pack a punch.

Patrick McLaughlin and his co-authors, specialists in policy analytics at the Mercatus Center, examined the use of restrictive or binding language in EOs beginning with George H. W. Bush in 1990 through Obama’s first term. “Restrictive” EOs—words that contain restrictive terms such as “shall” or “must”—tend to appear most often in a president’s first year in office, possibly as a reaction intended to quickly reverse the previous administration’s policies. Some administrations favor EOs with more teeth. Compared with EOs issued by other presidents, those issued by Clinton and Obama contained more binding terms such as “shall” or “must,” creating legal obligations for agencies, not merely suggestions or guidelines.

Do They Stick? Yes and No.

One study by Sharece Thrower, a professor of political science at Vanderbilt University, notes that of the 6,158 orders issued between 1937 and 2015, 25% were subsequently revoked, 8% were superseded and another 18% were amended, with most of those changes happening within the first 10 years of an EO’s introduction.

Not surprisingly, the greater the ideological gap between administrations, the greater the chance that an EO will be revoked, resulting in a game of “presidential ping-pong.” EO reversals are not always what they seem, highlighting what Cooper calls “the inertia principle,” or the tendency for EOs to stick and grow in complexity as they are modified in subsequent administrations.

Cooper notes that Reagan’s use of EOs to establish greater White House oversight over regulatory agencies, and thereby advance regulatory reform, remained largely in place during the Clinton and both Bush administrations. This regulatory philosophy hit an opposing ideological force with the Obama administration, though Obama’s actions hardly constituted dramatic reversals. While he repealed a George W. Bush EO that subjected guidance documents to the same White House vetting process as formal rules, Obama kept in place the Reagan-era regulatory review architecture.

Similarly, the Clinton-era EO 12666, Regulatory Planning and Review—which sought to make the regulatory process more efficient—has endured. Additional Obama-era EOs retained strong executive control over regulatory agencies, with a view toward constraining the rulemaking process and enlisting the input of businesses on the effects of regulations.

In addition to the danger of being revoked, executive orders without strong congressional backing are often at risk of not being implemented as intended by agencies. Scholars such as Andrew Rudalevige from Bowdoin College and Joshua Kennedy from the Georgia Southern University have separately documented that agency compliance with executive orders is usually not guaranteed, especially since independent agencies must answer to Congress, whose policy preferences may be at odds with the content of the executive order. In addition, Kennedy also argues that an agency head whose ideology diverges from the president’s will be less likely to follow through on executive orders and other presidential directives. Therefore, the full extent of an EO might not be realized.

Sending a Message

While the usage of executive orders has remained relatively steady since the 1970s, presidents increasingly tend to draw attention to their EOs with media events (Clinton’s Reinventing Government initiative), speeches (Obama’s “We Can’t Wait” agenda) and social media (Trump’s Preventing Online Censorship).

It is when EOs are used to prod the opposition or critics that they can backfire, magnifying conflicts among the branches of government and generally creating confusion as agencies attempt to apply directives. At best, they show decisiveness and commitment to a policy agenda; at worst, they circumvent debate on polarizing subjects and give the (albeit false) impression of anti-democratic, dictatorial whim.

Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell said that Biden’s initial flurry of EOs would hinder efforts at consensus building. To be sure, Biden is not the first president to send EO volleys across to the Capitol, though he is breaking a record for speed. The so-called Muslim ban issued by Trump (Executive Order 13769, revised as EO 13780 and supported by two other proclamations) remained contentious throughout the Trump presidency. The plethora of legal challenges to EO 13769 set the tone for much of Trump’s tenure.

Members of Congress may complain about the assertive message often sent by EOs, but they generally have not challenged them. In 2014, the House of Representatives led by Speaker John Boehner filed a lawsuit to contest the use of executive action by the Obama administration to use unappropriated funds to pay for healthcare subsidies under the Affordable Care Act. The House initially won favorable rulings, which were stayed upon appeal. With the change in administration in 2017, the House and the Trump administration jointly requested that the court put the case on hold while the parties negotiated a resolution.

The House That EOs Built

What may go unnoticed is that EOs add to the drama of government, putting undue emphasis on the president while undermining the hard work of consensus building, deliberation and decentralized decision-making that the Founders envisaged. EOs have led to the growth of the “new imperial presidency”—the post-Watergate shift in the balance of power in favor of the executive—as argued by Rudalevige. Even more important, Americans’ views have shifted toward a more expansive executive who can solve problems by fiat rather than a consensus approach enjoined by the Constitution.

Dennis Simon and several other scholars document the consequences of the public’s expectations of a president’s performance, including the belief that the chief executive is responsible for the prosperity of Americans and therefore accountable for the performance of the economy. In addition, a growing number of Americans expect the president to formulate the policy agenda for the country and ensure that it is passed into law and implemented. This view of presidential power may be fueled by the unilateral policy actions of presidents over the years. However, the reverse is also likely: presidents, aware of these expectations, decide to act unilaterally through executive orders. Either way, this phenomenon is quite different from what the Founders envisioned, a presidency that is not influenced unduly by popular politics, as noted by Simon.

While presidents might think there are upsides to legislating from the executive office, there are documented downsides. Andrew Reeves, a professor of political science at Washington University, provides evidence to show that the public reacts negatively to unilateral policymaking by the executive. More importantly, the continuous reliance on executive orders to accomplish policy goals has long-term consequences for the republic. Excessive reliance on EOs may increase polarization. (They also may be the result of it.) And the evidence of EOs’ effectiveness in achieving policy goals is decidedly mixed.

Executive orders perform many functions, from sending bold political signals to tweaking administrative processes. They are tempting but also run the risk of being temporary—rulemaking by decree rather than deliberation. It is time for politicians to rediscover the art of deliberative policymaking.