Does the Timing of the Trump Indictments Matter?

The timing of the Trump indictments raises legitimate concerns—but the cases are important as well

With every election cycle, political watchers talk about what makes this election more fascinating than any other. Normally, this is mostly hyperbole, but 2024 actually might be one of the most intriguing contests in our lifetimes: After all, the frontrunner for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination has been indicted four times. Nothing like this has ever remotely happened in American history.

Whatever one thinks of Donald Trump or his current predicament, being involved in such a tangle is not an ideal situation. To his detractors, there’s nothing particularly odd about these indictments from a legal standpoint: They say Trump is simply facing the consequences of his possibly criminal actions. But for Trump’s staunchest supporters, there is no question that the timing of these cases is nefarious. The “establishment”—the Deep State, Democrats, the media or some combination of these—has devised a cunning plan to indict and attempt to convict Trump as he seeks the country’s highest office once again. Still, there are those who may just be suspicious—why, for instance, are the cases against Trump moving forward only now, several years after most of the alleged crimes occurred?

I should say upfront that I am not a Donald Trump supporter. I opposed his presidential runs, and as someone who lived in the New York City metro area for several years, I was never a fan of his pre-presidential years. However, as a political scientist, I strive to look at Trump’s current situation with the eye of a clinician. While it would be arrogant of me to claim objectivity when I examine Trump’s business or political careers, I do think this lends me some credence when I say that I can certainly understand why many Americans would be suspicious of the timing of the current legal criminal cases filed against him.

In Politics, Timing Is Everything

Timing in politics is extremely important—and in the United States, it’s particularly unique. For example, look at one of the most brilliant aspects of the American political system: the separation of powers. The Founders gave each branch different powers, but it’s equally important how they set officeholders on different political clocks. Senators have six-year terms, House members have two-year terms and presidents come in between with four-year terms. Thus, each official looks at the political world with a different sense of time—though all share a preoccupation with when their next election is.

Why is this important in thinking about Trump’s current legal situation? The presidential election is coming, and on a rigid schedule: We will have one in November 2024 no matter what. But lawyers and prosecutors don’t work on a political clock. Of course, attorneys are not hermits unaware of when elections take place. But on a daily basis, they have to think about investigating alleged crimes, gathering evidence, interviewing witnesses and seeking indictments. Politics simply isn’t at the top of their list of concerns.

So when it comes to the indictments against Donald Trump, there are two possible explanations for what’s going on, depending on who you ask. Either this entire process is nefarious and gives us a real cause to be skeptical, if not downright hostile, toward the legal efforts to go after Trump—or, on the other hand, this is simply the workings of a legal system that moves to its own clock, one that is maddeningly indifferent to the clock that politicians and political watchers live by.

What we can say with a fair amount of certainty, though, is that no matter the intent, these cases have the effect of keeping Trump in the public eye. Admittedly, being in the public eye is not generally a challenge for Trump; however, these indictments keep him there in a way that enrages many grassroots Republicans and make it more likely that Trump will win the Republican nomination. This makes the challenge for prosecutors even more acute. They must strive—as they usually do—to make sure the process is seen as fair, and this is particularly challenging in these hyper-partisan times. In short, they need to show that they’re really not acting on a political clock, because the strongest of Trump’s supporters may have a hard time believing that’s true.

The Indictments, One-by-One

Keeping these differing senses of time in mind, let’s now consider each of the Trump indictments. Before making any conclusions about their timing, it’s vital that we analyze how different they are from one another.

The first involves Trump’s efforts to keep classified documents at Mar-a-Lago after he left the White House. While other presidents and vice-presidents—including Joe Biden and Mike Pence—have also been found to have classified documents after their terms, they have given those materials back to the National Archives instead of responding with defiance. This case is fairly straightforward, and the law seems clear: Trump had no right to keep those documents post-presidency, and the National Archives tried several times to retrieve them before the FBI got involved. There is no evidence that Trump declassified the documents before leaving office, which would have likely been his only possible defense. The original indictment by Special Prosecutor Jack Smith was later bolstered by a superseding indictment that Trump tried to destroy evidence of his efforts to hide documents.

In my mind, this indictment has the most merit and the least suspicious timing. These events occurred in the not-too-distant past—after Trump left office. Furthermore, Smith, who was appointed in November 2022, moved rather expeditiously with the case. In comparison to other similar investigations—say, the Durham report or the Mueller investigation that took years—Smith investigated and filed charges within a year. While each investigation is unique, Smith still moved about as fast as one can reasonably expect.

Two of the cases against Trump fall somewhere between unquestionably legitimate and definitely suspicious. One concerns Trump’s alleged actions to coordinate efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election—the steps he and others may have taken to thwart the counting of electoral votes.

Smith is the special prosecutor for both the documents case and this one, but the timing of this indictment is more suspicious due to the timing of the alleged crimes themselves. While news about classified documents at Mar-a-Lago came to light only in June of this year, Trump’s alleged efforts to challenge the outcome of the 2020 election had been well known for some time. The events of January 6 occurred nearly two years before Smith’s appointment as special prosecutor. So given how long we were aware of Trump’s possible coordination of those efforts, why did it take so long to appoint Smith?

The problem, I believe, lies with Attorney General Merrick Garland. When Garland was appointed, he opened investigations into what happened on January 6, and the Department of Justice has sought and achieved convictions of numerous individuals who stormed the Capitol that day. But all along, there have been questions about whether higher-ups—all the way up to Donald Trump—were directly involved in inciting the riots. There were also investigations of efforts by the Trump team to assemble fake electors in various states in late 2020 who would cast Electoral College ballots for Trump over Biden in states that the latter won. Garland should have realized early on that the normal investigative and prosecutorial procedures of the Department of Justice would not suit the situation. In his defense, one could argue that Garland was seeking to restore the workings of the Justice Department to normal after the controversies of the Trump administration. But it seems obvious now, and obvious for a long while, that a special prosecutor would be necessary.

It’s always hard to know what people are thinking and why they act—or don’t act. But in hindsight, it’s clear that Garland ought to have appointed Smith much earlier. Even an appointment in the summer of 2022 could have brought these cases forward by a few months—and that would have lessened some of the tension the timing now creates.

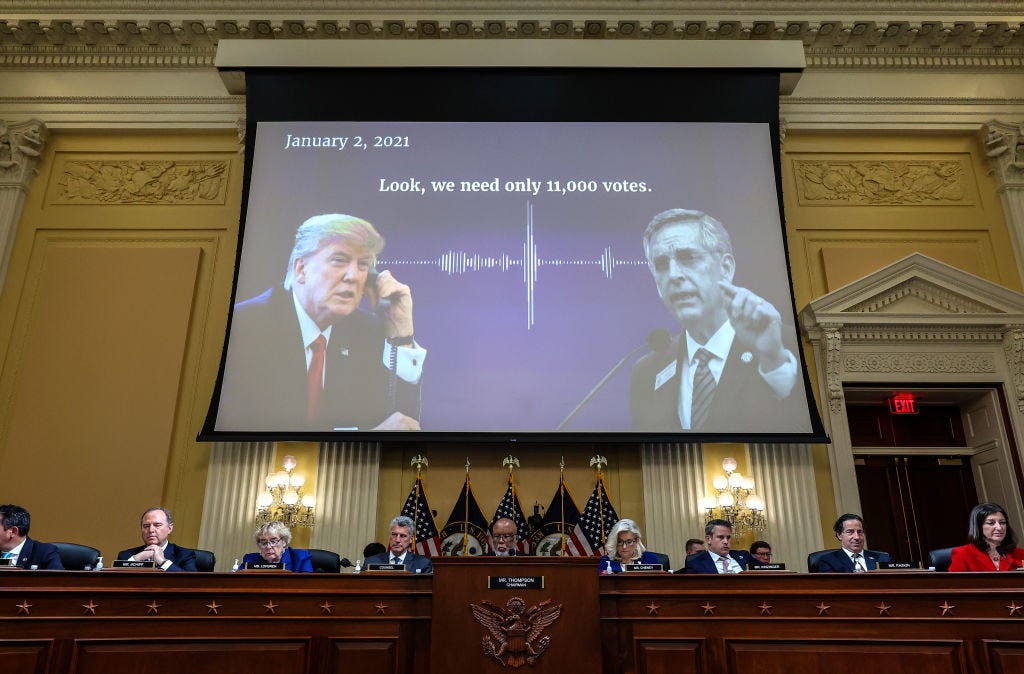

The other of the “in-between” indictments concerns efforts by Trump and others to interfere in the 2020 election in Georgia—including Trump’s infamous call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger in January 2021. In this call, it appears that Trump is urging Raffensperger to simply “find” some more votes, enough to deliver Georgia’s electoral votes to him. The case was complicated, with District Attorney Fani Willis ultimately indicting 19 people. The indictment was not simply about the questionable phone call: Willis charged Trump with a plot that involved many people, lots of pressure on different Georgia officials and the broader fake electors scheme. And the process was a lengthy one: Many witnesses had to be interviewed, and some refused to cooperate, requiring a number of subpoenas to be issued.

A further complicating factor was the use of a special grand jury: In Georgia, a special grand jury is used to investigate possible crimes, but it cannot issue indictments. Georgia’s special grand juries can only issue reports with recommendations. Thus, when that jury finished its work, Willis had to essentially start over with a traditional indictment-granting grand jury.

The use of special grand juries are not required under Georgia law. While a traditional grand jury is used to investigate many alleged crimes, a special grand jury is used to focus on one issue—one that may take extensive time to fully consider—and in Georgia, they’re often used to investigate political corruption. In investigating the former president, Willis likely felt the need to move carefully. Thanks to her effort to be abundantly cautious, the process slowed. And this slowness now raises timing questions.

Now we get to the final indictment, the New York City case—and here, the timing looks more suspect. Brought by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, this case involves the “hush money” that Trump paid porn actress Stormy Daniels. Trump had an alleged sexual encounter with porn actress Daniels in 2006, and as the 2016 presidential election approached, he arranged for his lawyer Michael Cohen to pay her $130,000 to deny the relationship. Because the payment was made to help Trump’s presidential campaign, it possibly violated campaign finance law.

Trump is accused of falsifying business records regarding the payment and how it was accounted for tax and campaign purposes. When a person is charged with falsifying business records, there is usually a second charge concerning a crime that the records seek to hide. But to date, no second criminal charge has been issued. If Trump has indeed falsified records, however, the public ought to be informed why he has done so—and what he might be covering up.

Even to someone highly critical of Trump, this case looks quite suspicious. It involves actions from many years ago, so why was this not prosecuted much earlier? Furthermore, at least initially, the Manhattan district attorney did not bring charges. The investigation was begun under former Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance in 2019—and it was only after the election of current DA Alvin Bragg that charges were brought. The fact that Vance did not bring charges, and Bragg did so only after one of his prosecutors quit in part because charges were not brought right away, raises legitimate questions.

The Importance of Trial Transparency

There is simply no way for the Trump era to end neatly. While those opposed to Trump may wish for some grand event that removes him from the political scene in dramatic and complete fashion, that’s probably an unrealistic hope. Instead, these indictments are more likely to play out like a long war, with countless skirmishes rather than outright victory. Given Trump’s large and loyal following, his acolytes will regard any legal actions against him as at the very least suspicious, and at the worst, ample evidence of the corruption of our political and legal systems. Indeed, a conviction could make Trump a kind of martyr and could also lead to violence.

Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be prosecuted. Many of the crimes of which he is accused are quite serious. If he is proven guilty of any of them, there is simply no way to ignore that. A conviction—or multiple convictions—could embolden Trump to go even further in attempts to undermine our constitutional republic. But much will come down to just how persuasive the cases are. The trials will certainly be telling.

Many people have already made up their minds regarding Trump’s guilt or innocence, with this decision really springing from one’s dislike or support for the former president. Therefore, it’s particularly important that we make it easier for all Americans to decide for themselves whether the indictments are legitimate or not. That’s why I think it would be good for the nation to televise the trials. There are good arguments for not televising trials—they give participants the opportunity to showboat, for one. But these will be unique in that they involve the former president of the United States—and one who seeks to return to the office.

In recent days, Smith has requested no cameras in the court. Smith may have a number of reasons not to want cameras—the norm is not to have cameras, he may wish to avoid Trump grandstanding and he may genuinely agree with the original arguments against cameras. Smith is quite a legal traditionalist, and he may want this trial to seem as normal and unremarkable as possible. However, the events of January 6 were unprecedented in American history, and as important as norms are, the momentousness of these events demands that the American public see what’s going on for themselves.

It is important to remember, though, that trying and potentially convicting Trump will not be a clean, overnight solution to the problems that beset the times. For all the structural brilliance of the political system the Founders created, our politics needs to have some level of trust as a foundation. Building trust in our political system will take time. As with a rocky personal relationship, that process will be a particularly slow one, since that trust has been broken. We are far from even starting that process. There is no guarantee we will ever get back to the high levels of trust in government we used to see in public opinion polls.

Indeed, trust in our political institutions and in our politicians is at record lows. This long predates the current political era, stretching back to Vietnam and Watergate. But the current era has pushed those levels of trust even lower. And tribal partisanship makes the task of restoring faith in government even harder. But the answer is not to ignore the events, because they cannot be swept under the rug. We need, as a nation, to face this, as difficult as it promises to be.

However, as a nation, we have faced even more dire circumstances before—even after the Civil War, the country was made whole again. We certainly can find a collective faith in each other and our government, and I think the Trump trials can be part of that process. To be sure, the timing of at least some of the indictments against him has contributed to the lack of trust in government—there is no denying it. But in the interest of fairness, transparency and true justice, we should all welcome a chance to see with our own eyes the cases against Trump—both their strengths and their weaknesses.