Diseases of the Rich

How the culture war ate everything

In recent years, the culture war has been eating the world. It has become the central issue of everything from state education policy to beer marketing. It used to be that a governor of either party who was concerned about his state’s schools would be fulminating about low test scores, high dropout rates, insufficient college admissions—not about which books on gender are readily available in the school library.

It’s not that we never had these culture war issues, or that we never had a gay panic before. But this sort of issue used to be balanced against the old “kitchen table issues” of taxes, inflation, employment and kids’ test scores. Yet those issues are now fading. Voters still list them as top priorities—but political entrepreneurs no longer treat them as the key issues that will tip elections. As one observer at a conference of “nationalist” conservatives reported, gatherings that used to focus on policy issues like tariffs and family subsidies now focus entirely on “grievance politics” like Ron DeSantis’ war with Disney.

But isn’t this something of a luxury? How few problems must we have, if contests over culture and status and how other people make us feel are our central concerns?

The enormous bitterness and the frequently apocalyptic tone of our culture war disguises the fact that it is a luxury of the rich.

Diseases of the Rich

We really are amazingly rich. Some recent figures about the general level of wealth in the United States versus Europe have been making the rounds. Economist Noah Smith surveys the data and sums it up: “The median American earns more income than the median resident of almost any other country on the planet.” Smith continues:

And it’s worth noting that higher average incomes partially cancel out the deleterious effects of higher inequality. A good measure of inequality is the relative poverty rate—the percent of people living at or below half of the median income. In the US, this number is higher than for other rich countries—in 2019 it was 17.8%. That means that someone at around the 18th percentile of income in America in 2019—a working-class person on the edge of being considered poor—lived in a household making $21,400 a year. That’s ... about 84% of the median income of households in the UK.

No, really. Another new analysis of the data looks at the size of the middle class in America relative to European countries and finds that while America appears to have a smaller middle class, this is only because our middle class is defined relative to a much higher standard. According to a recent report from the Pew Research Center:

In most Western European countries studied, applying the US standard shrinks the middle-class share by about 10 percentage points ... [I]n Denmark, the share of adults living in lower-income households increases from 14% to 28% under the US standard. And a slight majority of adults in Italy and Spain (an estimated 53% each) are in lower-income households by US standards.

In short, a good chunk of the European middle class doesn’t even qualify as middle class by American standards. And these are some of the wealthiest and most developed countries relative to the rest of the world. We are richer than the richest.

This is not to say that there are no poor people in the U.S., or that we have no important economic issues to address. The point is to explain why those issues are no longer at the forefront of a lot of our political debate right now.

For a large portion of our population, economic growth and increased wealth no longer seems like a top priority—because they can take it for granted. More to the point, this is the portion of the population that tends to be most culturally and politically influential. The college-educated upper-middle class are the people with the most time and money to devote to political activism, and they are the most likely to spend too much time on social media feeding its partisan echo chambers.

The result? There’s an old Tom Lehrer joke about a doctor who specializes in “diseases of the rich.” Well, today’s politicians also specialize in the complaints of the wealthy.

The Politics of the Semaphore

In the 1960s through the 1980s, our dominant political issues included the War on Poverty (for the left) and the Misery Index (for the right).

On the left, this has since been eclipsed by environmental and culture war issues that are often more symbolic than practical—issues that are less about one’s own well-being or the practical impact on one’s own life than they are about showing that one is on the right team and the “right side of history.”

For the right, the complaints are less about economic issues than cultural or lifestyle issues. The contest between freewheeling modernity and traditional values is the lens through which the right increasingly sees everything. This is why a certain faction on the right backs Russia against Ukraine, because they can only see foreign policy through the lens of our domestic culture war, where Vladimir Putin is seen as an opponent of “wokeness.”

Across the spectrum, these lifestyle issues have risen in prominence as our chief political concerns, pushing out the old “kitchen table” issues. If the agenda of the activist left has become about “virtue signaling,” the agenda of the activist right seems to be about signaling back one’s contempt for the virtues signaled by the left. It’s all the politics of the semaphore.

The View From the Top of the Pyramid

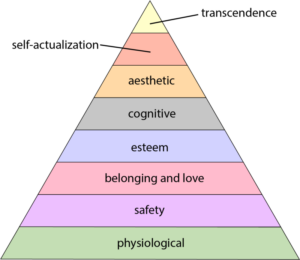

What we are seeing is a large-scale demonstration of Maslow’s Pyramid.

In 1943, American psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed a “hierarchy of needs” to explain human motivation. At the bottom of the pyramid (the shape usually used to illustrate Maslow’s idea) are basic physical needs like food, clothing and shelter. Higher up are “safety and security” needs, like a steady job and healthcare. But once people have secured these basic needs, Maslow argued, they are able to focus on needs that are less urgent and concrete and more psychological and intellectual.

No longer so concerned with keeping our bellies full or a roof over our heads, we are free to obsess over our spiritual lives—and too often, not in a good way. Our political controversies are about whether we’re living a traditional lifestyle or a green lifestyle, or whether our men are masculine enough or we’re too stuck in an outdated “gender binary.” Maslow posited that as we move a step or two up in the pyramid, we shift to a concern with “belonging” and “esteem,” but this can take the unhealthy form of a neurotic obsession with status. It can mean attempting to force recognition of our status on others—and viewing status as a zero-sum game, where if someone else rises in status, you must be going down. Sound familiar?

The Blue Dots of Outrage

What makes these battles over status seem so neurotic and unhealthy is their lack of a sense of proportion. We were once concerned about “one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished,” or we fought over civil rights flagrantly denied to one-tenth of the population. The latest vicious battle is being fought over transgenderism—an issue that directly involves at most a few tenths of a percent of the population.

The point is not that these people’s lives are unimportant or that they don’t deserve protection. Nor would I deny that some overzealous attempts to protect them have taken on ironically puritanical and censorious forms. The point is that, viewed with a sense of perspective, this is a relatively small controversy that could be addressed with carefully calibrated incremental reforms and should not require the overturning of the whole existing social or constitutional order, one way or the other. Drag Queen Story Hour is much too small a phenomenon to be either the end of our civilization or its salvation—yet the amount of energy it commands in our current culture war implies that it is.

This reminds me of another psychology study that caught my attention a while back, which I call the “blue dots of outrage.” Researchers asked people to identify the number of blue dots and purple dots in a series of images, but when they slowly reduced the number of blue dots, people began interpreting purple dots as blue. They attempted to change their interpretation of the world so they could keep on seeing the same number of blue dots. Similarly, the researchers concluded, when there are fewer serious problems in the world, people tend to invent ways to find more of them.

When our basic survival needs are met, we tend to move up Maslow’s Pyramid to address less urgent spiritual needs—but we also tend to interpret those spiritual needs as if they were basic survival needs.

The problem with our current cultural and political obsessions, our diseases of the rich, is not that they are unimportant or that there is no reason to care about them. The problem is that we treat relatively minor complaints about our lifestyle, and all too often our emotional upset at somebody else’s lifestyle, as if they are life-and-death issues.

Painting, Poetry and Drag Queen Story Hour

We’re living through a twisted version of something John Adams predicted in a letter to Abigail Adams: “I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, and naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.” Instead, our forebears mastered agriculture and commerce so we could have the leisure to argue over “woke casting” in the latest J.R.R. Tolkien adaptation. Somehow, this seems less inspiring.

Maybe our focus should be less on the latest flotsam and jetsam of the pop culture war and more on what Adams had in mind: the creation of culture, of “painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary”—and I suppose we could also use some tapestry and porcelain. And we could undertake that job with some appreciation of how fortunate we are to be able to think about it.

At the top of Maslow’s original hierarchy, above petty concerns about social status, are things like “creativity,” “achievement” and the actualization of one’s potential. Perhaps if we ascend our hierarchy of needs a little farther, we will find meaning and a sense of purpose in that.