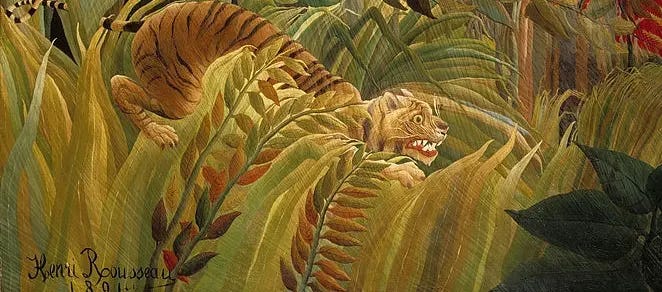

Dangers Stalk the Global Jungle

A new book by David Kilcullen argues that to maintain its military dominance, the US must learn from its strategic competitors and other rivals

Public debates in the United States about national security frequently center on the cost effectiveness of specific weapon systems while deeper questions about strategy often go unexamined. In The Dragons and the Snakes: How the Rest Learned to Fight the West (Oxford University Press, 2020), professor and military analyst David Kilcullen lays out how an array of state and non-state adversaries have evolved to challenge and erode the dominance of the United States and its allies and what, if anything, the West might do in response.

Kilcullen drew the title from James Woolsey’s testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee in the course of his confirmation process to become CIA director under President Bill Clinton in 1993. During those hearings, Woolsey said that the US had slain a “large dragon” in the form of the Soviet Union but faced “a jungle filled with a bewildering variety of poisonous snakes” embodied by criminal cartels, terrorist groups, ethnic militias, and other non-conventional threats.

The “West” of Kilcullen’s book consists of the countries whose military structure and warfighting style emphasizes networks of sensors, integrated communications, and precision weapons to dominate the battlefield. The apotheosis of this “Western way of war” is the Gulf War, where US-led coalition forces decisively defeated the well-equipped army of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1991, ejecting it from Kuwait. A decade later the invasion of Iraq in 2003 also featured fearsome US airpower and land forces. However, the campaign and subsequent insurgency during the occupation of Iraq revealed the limits and weaknesses of the Western approach.

Likening it to the “high tide of the Confederacy” at the Battle of Gettysburg, Kilcullen says the failure of “decapitation” air and missile strikes to kill Saddam and his sons at the opening of the invasion showed that the West’s dominance was ebbing. Moreover, the early battlefield successes during the drive on Baghdad had little to no bearing on what became a brutal and extended counterinsurgency campaign. He writes:

The vulnerability of precision systems to inaccurate intelligence, their dependence on data and connectivity, and their irrelevance against an amorphous, cell-based enemy who blended into the physical and human terrain of a society and culture we barely understood became increasingly obvious as the war dragged on.

Kilcullen says the interval between the Gulf War and the Iraq War saw both state and non-state opponents of the West learning both how not to fight and ultimately how to fight the United States and its allies. The book’s central—and most resonant—theme is that the West is in danger of seeing its dominance, and the world order on which it is based, slip away. The world’s power structure is constantly changing, and Kilcullen delves into how the dragons and snakes evolve through observation and bitter experience to improve their capabilities and craft their strategies.

The book draws from a deep well of firsthand experience. Kilcullen, a retired lieutenant colonel in the Australian Army and currently commissioned as a lieutenant colonel in the Australian Army Reserve, has served in a number of peacekeeping and counterinsurgency missions in East Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East. He has also worked as a civilian counterinsurgency adviser to US and allied governments. This experience informed a number of his previous books, including Blood Year: The Unraveling of Western Counterterrorism (2016) and Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla (2013).

His latest book includes a number of comprehensive case studies showing how various “snakes,” including al-Qaeda and other jihadi groups in Iraq, and Hezbollah in Lebanon, have transformed and adapted. In each case, Kilcullen describes how the crucible of fighting Western forces like Israel’s shaped the organization, tactics, and even equipment of each group.

Terrorist and insurgent groups and militias have to be able to respond quickly to their enemies’ methods if they are to survive, let alone to succeed in achieving their goals. Conceding that this is more of a truism than a revelation, Kilcullen studies how such irregular forces learn and adjust. Such a process is characterized by gradual, conceptual changes during periods of peace or inactivity and “growth spurts” during active operations and combat. Losses taken during combat are the most instructive, he asserts, quoting a saying from his cadet days: “Doctrine is written in blood.”

The key, Kilcullen observes, is to constantly adapt to changing enemies and battlefield conditions. This is intellectually clear but change rarely happens without sufficient motivation. Armed forces that handily win most of their battles with minimal loss may not feel the pressure to improve or innovate. Lose too many battles, of course, and the organization ceases to exist.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspects of the book are the latter sections that show how the “dragons”—major powers Russia and China and select lesser powers, such as Iran and North Korea—have incorporated snake-like transformation into their strategies for confronting the West. Such countries have developed non-conventional means for achieving goals inimical to Western interests through misdirection and pursing activities that are not perceived as militarily threatening. As in the chapters on snakes, Kilcullen documents how these dragons have learned from their own successes and mistakes and through careful analysis of those of the West.

If Kilcullen asserts that the Western way of war is no longer dominant, he does not go so far to say that it is irrelevant. In fact, Russia and especially China are pursuing aggressive military modernization and advanced weapons procurement programs. Kilcullen says this arms buildup is to advance their own interests independent of a direct conflict with the West. Of course, these weapons enable them to challenge the United States and its allies militarily if necessary. In addition, new weapons encourage the United States to develop and deploy expensive weapons of its own in an effort to maintain superiority and thus force the United States to expend resources it might use more effectively elsewhere.

Kilcullen strongly and consistently builds his evolution and adaptation thesis throughout The Dragons and the Snakes. The book includes deep historical context and is extensively footnoted and well indexed. He devotes somewhat less attention to developing prescriptions for what the West might do to stem the tide. He breaks out three potential strategic responses:

Double down: Reject the inevitability of relative Western decline and pay any price to maintain the current world order;

Embrace the suck: Make peace with the loss of Western dominance and manage a suitable retrenchment; or

Go Byzantine: Play for time by developing armed forces and policies that enable a long-term role for the West, if not a preeminent one, in the manner of the eastern Roman Empire.

Kilcullen ultimately sees these strategies as mostly strawmen, using them to examine and reject many of the arguments currently being proffered in national security policy circles. Fortunately, the author is prepared to offer a new military model that essentially boils down to learning from the enemy. While eschewing the brutal methods of totalitarian societies, Kilcullen says the West should start taking pages from the dragons’ playbooks: play for time while countering their efforts to misdirect.

Kilcullen says a sort of Byzantine strategy combined with a willingness to adjust to the enemy’s tactics would be a way forward for the West. The vast investment in counterterrorism and special forces since 9/11 has shown that the West can be as snakelike as it needs to be. As for dealing with the dragons, he suggests maneuvering through guile, even trickery. This would mean a willingness to pretend, as our enemies do. Kilcullen writes:

The imperative for military thinkers in this new environment is to break out of our conceptual comfort zone, consider the consequences of the past quarter century of Western dominance and its effects on our adaptive enemies, and develop viable options that might help our societies evolve and survive for the long twilight struggle ahead.

Certainly, a good first step would be to pay close attention to what Russia, China, and the “baby dragons” are up to and see their disinformation and misdirection efforts for what they are: strategies to defeat us.

Kilcullen’s The Dragons and the Snakes is a timely invitation for the West to get its strategic house in order with some new thinking.