Conspiracy Theories in Contemporary Political Discourse

Ben Klutsey and Hugo Drochon discuss the attraction of narratives that provide meaning and certainty

BENJAMIN KLUTSEY: Our guest today is Hugo Drochon. He’s assistant professor in political theory at University of Nottingham in the U.K. He is a political theorist and historian of political thought with interests in Nietzsche’s politics, democratic theory, liberalism, centrism and conspiracy theories, which is what we’re going to talk about today.

A Theory of Conspiracy

KLUTSEY: First question to you, Hugo, is what is the difference between a conspiracy theory and, say, a regular theory in the social sciences that has not yet been proven?

HUGO DROCHON: Yes, a great way to start. Thanks for that question. [laughter] There’s a follow-up question also, which is, can we make a distinction between a conspiracy theory and perhaps a theory of conspiracy? Which is, I think, one of the big challenges today, actually, because there’s quite a bit of confusion when we talk about what do we mean by conspiracy.

If we mean the real hardcore conspiracy theory, actually, it’s probably less of a theory than it is a belief. Normally, the full-on version is, there’s a small group of unknown people who control everything in the world—not just politics, but also economics and even the environment, which is why you get climate-change-hoax conspiracy theories. That’s the hardcore version.

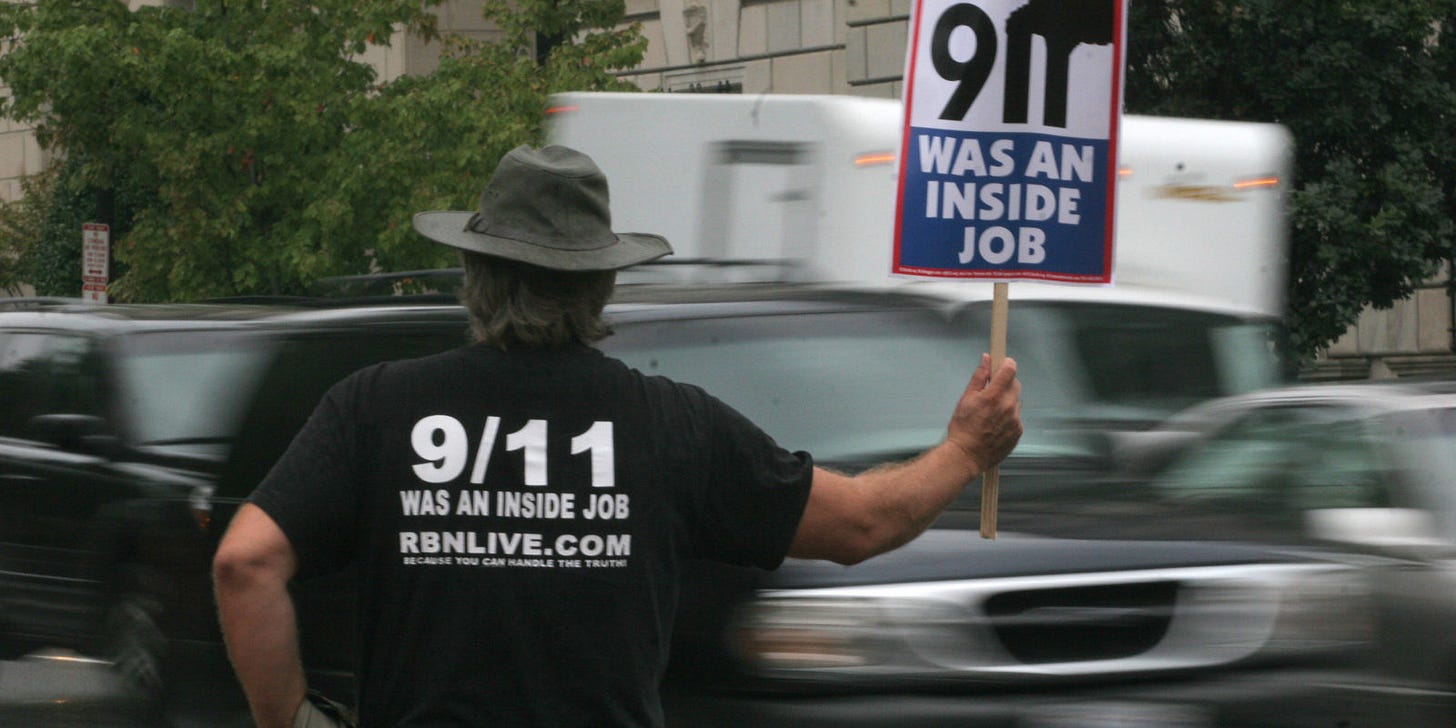

When we talk about conspiracy theories, I think it’s more of a belief because we talk about conspiracy theories having self-sealing capacities. If you’ve ever spoken to a conspiracy theorist, you’ll know exactly what’s meant by that, which is if you try to say to somebody, “9/11, it wasn’t an inside job. It wasn’t the FBI in league with Mossad or I don’t know what. It’s actually al-Qaida flew a plane,” the response you often get is, “Well, you would say that because either you’re in on the plot or you’ve been brainwashed,” et cetera, et cetera.

The self-sealing capacity of the ideas—there’s a core belief, and any new information is never going to challenge the core belief. It’s always going to come and reinforce it, actually. They’re always going to come in with new information and say, “Well, I believe this, and the reason you’re trying to disprove me or tell me otherwise is precisely—that is a proof that I’m right.”

It’s not really—actually, “conspiracy theories” is probably the wrong word, is what it’s become. There’s an interesting thing because conspiracy theories at the beginning of the 20th century . . . It’s only when there’s questions of JFK, Watergate, that conspiracy theories take on this slightly pejorative sense that it has today. Before, it was more of a word of art. It was just like, “Oh, I think something happened. I think it was a plot,” as opposed to it was something else.

To go back to my original point, which is, I think we still have to have that space where we could say, “Oh, there was a conspiracy, or there was a coup.” We saw there was a coup in Mali recently. Well, that’s a coup. That was a conspiracy. There’s a category of analysis that we’ve had all the way back, at least from Machiavelli. I say, yes, conspiracies that exist, and we need to be able to theorize that but to separate that from the conspiracy—at least the hardcore conspiracy theory, which is to say, “No, there’s a small group of people who control everything, not just specific events but the whole thing.”

KLUTSEY: How do you draw the distinction between a healthy skepticism of the official story and falling into conspiracy thinking?

DROCHON: Yes, it’s a great question also within a democratic context, because in democracies we need critical publics. We need them to be critical, but not taken by conspiracy theories—because conspiracy theories, it presents itself as being critical but already knows the answer, and no amount of information is going to change what they believe.

I think that’s the fundamental distinction, is that certain people might put forward a hypothesis: “Oh, I think this is a conspiracy.” There’s people talking about, “Oh, was there a conspiracy between Trump and the Russians?” People said maybe there’s something going on there. The critical even cynic might say, “Okay, maybe there’s a conspiracy going on.” Then perhaps, seeing all the facts, would say, “Actually, no, it wasn’t a conspiracy. There was things of influence, or maybe there was an alignment of interest, but it’s not a conspiracy.” Conspiracy theorist would say, any new information will never challenge that fundamental belief.

I think that’s the openness—there’s a question of, without getting too philosophical about it, but epistemology of knowledge. One group says, “Okay, well, this is how we go about knowledge: We check certain things. Or I have this hypothesis; we check it out in terms of the facts that we might have,” which is always limited. We never know the full story, of course. Within that we get a sense, “Oh, maybe this is wrong, maybe this is right.” The conspiracy theorist won’t have that. They will always be right, and no new information. I think that’s one of the ways to distinguish the two.

Democracies vs. Authoritarian Regimes

KLUTSEY: Interesting. You mentioned the democratic context. I want to come back to that. Is there a rise of conspiracy thinking? I was wondering whether you see more conspiracy theories within democracies than in other regimes or not.

DROCHON: Yes, great question again. We’ve started doing a bit—a lot of this research is based on surveys we’ve been doing with YouGov, a polling company, since 2015. It’s true that, first of all, the quantitative data was really focused on U.S. Where we came in to say, “Well, we have all this data on the U.S. What does it look like in Europe?” Actually, there’s not much difference between the U.S. and Europe, which some people say, “U.S. is really—there’s a specific phenomenon. There’s ‘X-Files’ and all this kind of stuff. It’s really the land of conspiracy theories.”

No, because you look at Europe, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, you go back to that stuff, David Icke, if there’s any U.K. listeners—David Icke, who thinks that lizards rule us. It’s there too, and it’s similar. However—it’s similar, and it’s probably slightly more prevalent than we would normally take it to be. It’s not just minority support for the surveys that we have.

If you ask a number of different conspiracy theories—9/11, moon landings were faked, Holocaust denial, these types of things—around 50% of respondents will answer yes to one of those questions. They won’t answer yes to all of them, but they’ll answer yes to one of them. The cabal question, the key hardcore conspiracy theories that I started off with, that varies between 15% to 20% within U.S. and in Europe.

Sorry, this is a very long way to answer your question. We were like, “Okay, but this is a relatively Western context; what does it look like outside of the West?” And we’ve started doing a bit of polling outside of that. In authoritarian regimes, these types of beliefs are much more held than they are—if it’s around 50% in U.S., Europe, it gets up to something like 70% I think in Nigeria, for instance. We did Turkey also, which was higher. It is higher.

There’s a really interesting question, though, within that, which is that if it’s a majority belief, is it still a conspiracy theory? What is it? For instance, if you look at a lot of the polling that’s done in the Middle East, especially in terms of 9/11, there’s 70% to 80% within the Middle East who thinks it is an inside job. Why? Well, look at the consequences of that on the Middle Eastern world, the invasion of Iraq, et cetera.

Obviously, there’s a strong link, often, with belief in conspiracy theories and feeling threatened by something outside. You get much higher in the Middle East. If that’s the case, if it’s a majority belief, what is its relationship with being a conspiracy theory, yes or no? Don’t ask me, because I don’t have the answer to it yet. It’s something we’re trying to explore as we go forward.

KLUTSEY: In terms of rankings, what’s the most prominent conspiracy theory across the board?

DROCHON: It slightly depends where you ask the question, like in the Muslim world, 9/11. I think actually the one . . . and JFK is still very prominent in the U.S. It’s gone back down a bit, but there’s still close to 50% of the population that will say yes to that. The core one, though, still going back—because then you get quite low ones. Like Holocaust denial, we get like 2%. It can be quite low. “Climate change,” for instance, “is a hoax” has gone down actually over the last while. In the U.S., I think it was something close to 30%; it’s gone down to something like 15%.

The one that stays continually there, and that’s why I think we’ve put so much focus on it, is that cabal one, the one about the small group of people controlling everything. That’s always 15%-20%. Sometimes it goes up to 30%. That one seems to be more universally the one. And that’s why we use it as a bit of a baseline because it’s one you can find everywhere. It goes up and down slightly, but it’s always prominently there, which is why we put so much emphasis on it.

The Cabal Theory

KLUTSEY: The cabal theory is that there is a small group of people who control everything?

DROCHON: An unknown small group of people who control everything—and not just politics, but also economics, the weather. They’re the ones who can say, “Oh, there’s going to be a typhoon here,” whatever it might be, which is why it’s linked to climate change conspiracy theories.

KLUTSEY: Where does that come from?

DROCHON: One of the classic examples of that is the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the idea that there’s this Jewish conspiracy; they meet in this Budapest cemetery every couple of years to decide if everybody’s done what they’re meant to do.

The thing with conspiracy theories is that it’s probably something like an anthropological constant. If you think about it, even at an individual level, there’s always moments where we’re feeling a bit more vulnerable, probably a bit more paranoid. I don’t know. Have you lost a job? Your girlfriend or your boyfriend’s left you, and you tend to project intentions on other people. Or not getting promoted, it’s because they’re out to get me, et cetera. I think we all have a bit of that in any case.

If you extend that to a group level, think about it. “Oh, we have a group,” back when we were still living under rocks and everything, and you are part of a group, and you see this other group arriving. You’re like, “Well, are they going to be nice? Are they here to kill us? What are they going to do?” You tend to project agency onto them.

I think that’s probably part of our psychological makeup. If you just extend that a tiny bit, you can get, “Well, it’s not just, ‘These are the groups who might be threatening,’ but actually, the whole world is organized along a certain way.” People are attracted to that. I think it’s often because they themselves feel they’re a bit at a loss within the world. They’re trying to find something that can explain how the world is organized, which, again, is something we all reach for.

I think that’s why religion plays such an important role in many people’s lives. And religion tells you one of those stories, which is there’s good forces, there are evil forces, this is how you should behave in the world.

Conspiracy theories give you that too, which is, “Okay, well, there’s these bad guys who are there, and they control everything. But we’re not really sure who they are. It’s hard to figure out who they are, but that’s why you’re not getting ahead in life as much as you want.” People are drawn to that, but I think there’s a slightly empowering element to it.

If conspiracy theories come from a sense of exclusion, then saying, “Oh, well, now I understand the world,” that gives you a sense at least of intellectual empowerment to say, “Well, I understand why things are happening to me now.” That’s a fundamental need that we all have. Conspiracy theories are just a slight extension, perhaps an extreme version of that, but we all have that. I think there is a fundamental human need.

Antisemitism

KLUTSEY: I want to come back to the point you made about religion and seeking meaning and how people latch onto conspiracy theories. But I’m interested in the question of how this ties in with antisemitism as well. Can you elaborate on that?

DROCHON: Yes. Well, I thought you were going to ask me about Nietzsche, actually.

KLUTSEY: We’ll get there. [laughs]

DROCHON: We’re just starting. We’re trying. We figured out how this—as I said, we’ve asked questions about Holocaust denial, which is quite low. But then that doesn’t seem to represent well the kind of society, the type of things that we see in society more generally.

Actually, the relationship between the Holocaust denial question and the cabal question is quite interesting, where Holocaust denial, you only get 2%; it’s very low. But the cabal one is 15%, 18%, whatever it might be. There’s a gap within that. The cabal doesn’t always have to be Jews. Sometimes it is Freemasons or the Jesuits or whatever. You have different versions, but of course, it’s quite easy to put the Jews within that.

Structurally, a lot of antisemitism looks quite similar to conspiracy theories. The Jews are there. There’s this—if you look at QAnon today, the whole thing of pedophilia can go all the way back to Christian blood libel, this idea that Jews were stealing young kids to do their satanic rites. There’s this long trajectory that’s there.

I realize I’m not exactly answering your question. We’re trying to explore that link because it looks like—it’s interesting because what we’re trying—we’ve started this new project on the link between the two, because we’ve noticed that just simply teaching the Holocaust often is not enough to combat antisemitism. Just telling the truth is not enough to combat antisemitism, and that’s something similar to conspiracy theories. If you just tell them, “No, look, 9/11, it was al-Qaida, look, blah, blah, blah,” they’re not going to believe you.

There’s something interesting between the two which we’re trying to develop to get a sense of, “Well, how do you go about, then, trying to address questions of antisemitism?” Structurally, you could see the links between the two, and we’re trying to explore more deeply.

Actually, there’s not that much quantitative work that’s been done in antisemitism so far. A lot of it has been, “Here’s my definition of what antisemitism is, and let’s do some polling data on that.” For the more methodological people, they say, “Well, that’s fine, but we need a validated measure of antisemitism in a way that we’ve managed to develop a validated measure of conspiracy theories.”

Without getting too technical about it, you just do this empirical work to make sure that you’re really measuring conspiracy theories as opposed to anything else. What we’re trying to do right now is try to develop a measure of antisemitism so we can then get a better sense of the role and where it’s coming from in society and why.

Religion and Narratives of Meaning

KLUTSEY: Now we’re on Nietzsche. You’ve noted elsewhere that some of this new type of conspiracy thinking is related to Nietzsche’s idea of the death of God and the loss of a single religious or other narrative to give meaning, purpose and community to people. Could you explain or expand on how you think that narratives of national or religious identity play a role in conspiracy thinking?

DROCHON: Yes. Great. The relationship between religion and conspiracy theories is a super interesting one, and yes. But I think Nietzsche—he wasn’t talking about conspiracy theories, although the ethics of suspicion that we associate with Nietzsche is often then used by a lot of continental philosophers that brings us into conspiratorial thinking.

As you say, I think that conspiracy theories—people are drawn to them because they have difficulty in giving an overall account of their lives. There’s different ways of saying that. As you say, one of them could be the national story, too, of the society when and which you live. The beacon on the hill in the American context. So, this is the story that you want to tell yourself about the French Revolution, whatever it might be.

These are stories, and everybody needs these types of stories, I think, to make sense of the lives that they’re living and what they’re trying to achieve. Conspiracy theories play a role. Religion plays a role in that, and conspiracy theories play a role in it. There’s some analogies, which I mentioned before. Religions sometimes tell you these Manichean stories about good and evil. Conspiracy theories tell you the same thing.

A lot of the work, especially the more historical, cultural-study work that was done in the U.S. at the beginning, was drawing a strong link between communities that were very religious—perhaps the millennialism too, where there’s going to be the judgment day coming. You get some of that still with QAnon. There was supposed to be the storm, was it, where Trump was supposed to lock Hillary Clinton up and liberate all the Americans?

Those communities are indeed often attracted to conspiracy theories because the structural thinking is quite similar, but it doesn’t mean that there’s a direct link between religion. Just because you’re more religious doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to be more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. It depends on what type of form that religion takes. If it’s very black and white, et cetera, then it can be.

I think this was what came out of our work, was people who are attracted to conspiracy theories often feel they’re excluded for whatever reason. And sometimes, if you are religious in a majority-religion country which you share the majority religion of that country, you are actually less likely to be a conspiracy theorist because you’re fully engaged with your society. You don’t feel excluded in any sense. However, depending which community, if you’re atheist in a very religious community, actually maybe there you’re more likely to be a conspiracy theorist, or if you’re in a minority religion compared to the majority.

All these things have to do with a sense, and it’s a personal sense—whether it’s true or not is another matter—a sense of exclusion that draws you to conspiracy theories because then it gives you an account of what’s happening in the world.

Are Conspiracy Theories on the Rise?

KLUTSEY: I would imagine that in times of deep polarization, where people feel that they’re excluded or they feel threatened by the other, are we likely to see a rise in conspiracy theories? Maybe that ties into a question more broadly of, what does the data say about where we are with conspiracy theories? Is it on the rise right now? Is it peaked? Is it on the decline?

DROCHON: Yes. I think there’s two questions there. It’s through that context where there’s uncertainty. An event happens, and we’re not really sure what that’s been. Then it’s often true that conspiracy theories fill the void. In the same way as we discussed earlier, you see this new group that are coming at you. Are they well-intentioned or not? You don’t really know, and you attribute agency to them even though—I think that’s actually one of the big changes in the modern setting, is that we attribute agency to probably abstract institutions as opposed to individual groups of people. That’s quite interesting.

Normally, yes. In times of fear, uncertainty, yes, conspiracy theories rise. That’s true. Having said that, we have done a bit of work, and I know this is slightly controversial. We’ve done a bit of work since, again, the pandemic, where there’s uncertainty. What’s happening? We don’t really know. Also, the lockdown gives you a sense of forced isolation. You feel excluded.

And the other element obviously to throw in there, which does play a role, is social media. People are exchanging on social media, and we know simply the business model of social media is the attention economy. They want to retain your attention, and we know that anything that’s a bit controversial, salacious, sexy, whatever, retains your attention more than a headline of The New York Times. Obviously, conspiracy theories are a bit more salacious and a bit more fun than just the regular news, so it spreads more.

Having said that—and we’ve discussed this before—our studies tend to suggest that even if conspiracy theories are more visible, doesn’t necessarily mean to say that there’s more of them, And that’s a fundamental thing to keep in mind. On the one hand, because conspiracy theories are actually probably being a lot more prominent than we’ve usually accepted them to be. It’s not like these people weren’t there; it’s probably just that we didn’t see them as much.

I think the big thing, the big difference with social media is . . . In the past we have this line in the conspiracy theory group of studies, the “green inkers.” The green inkers were people who wrote letters to the editor of national newspapers, whatever, New York Times, whatever it might be, Washington Post, whatever it might be.

The editors immediately knew—all these letters coming in, but for some reason there were certain groups of people who would write in green ink. They became known as green inkers. And they knew immediately, “Oh, it’s green ink; this is conspiracy theory stuff.” They knew they could vibe it out, but it’s not like those green inkers didn’t exist. It’s just that they never made it through to the letters of the editor because there was guardians or there was a filter process, journalists. But those green inkers are always there.

Now they just go on social media, and they just post all the stuff that they wanted to write otherwise, which they were sending and trying to get out there and get their voice expressed. Now they don’t need a middleman anymore. They can just do it on social media. You see it a lot more; doesn’t mean necessarily that there’s more of it. I think that’s one of the key distinctions. And there’s studies from the beginning of the pandemic to now, where we’re hopefully touching the end of it—hasn’t changed really that much.

There is another question in there which is, what does that mean in terms of—to go back to democracy question, what does that mean in terms of our public discourse? Because it’s always this difficulty that we need a critical public for democracies to work. That’s an essential element. But it has to remain critical, and that—of course it needs to be critical of the official line and whatever we’re getting. But it still needs to be open to refutation, were it to come about, whereas conspiracy theories are critical of the official line but are not open to refutation at all.

I think that’s part of your polarization question, which is if our public discourse is dominated by conspiracy theories on either side, that’s going to be very, very difficult to handle. And social media, I think, has played a role in that. And we need to get back to the situation where it’s more a critical discussion, but one in which there still can be found some common ground. That’s definitely one of the challenges that we have today.

KLUTSEY: I see. I think you’ve written before that during COVID, we’ve seen a rise of conspiracy theories around vaccines. But as people got more information, that has declined, which seems positive. But I’m not sure that it fits with the general sealing theory. (Is that the right term, sealing?) Because people are not saying, “Well, you would say that because . . .” Is that just a situation where it’s different?

DROCHON: That’s a good one, and I think you could compare also U.K. and U.S. Before the pandemic there were similar levels of anti-vax feeling, if you want to call it like that, resistance to vaccination. The U.K., that actually decreased relatively rapidly, one, because the vaccination seemed to be working well. And actually, I think if that’s the piece you’re referring to, it’s like, well, the answer to anti-vax conspiracy theories is not really trying to answer them; it’s just to vaccinate more people.

Because the more people get vaccinated and it’s like, “Oh, actually it doesn’t look that bad. It’s okay.” The difference in this country, for instance, is that it became somewhat a game of political football. Whereas in the U.K., it was a national endeavor, in the U.S. it became this, “Oh, are you vaccinated? Yes or no?” It was a way of showing one’s political color.

You do have conspiracy theories that are sometimes driven by political positions. And the challenge then is to distinguish, is this a conspiracy theory belief as such, or is it something that’s driven by political partisanship, which when the political partisanship moment is gone, it decreases back to the core conspiracy theory moment?

I don’t know if that entirely answers your question, because it’s very hard to rationally engage with conspiracy theories. That’s the theme. And so, I think the ways to think about it, around it, and one of the ways is like, “Okay, we’re not going to address anti-vax conspiracy theories altogether. We’re just going to try to vaccinate as many people as possible and let that take its own role.”

Obviously that has to happen within a certain context where there’s trust and when there’s belief and everybody’s on board. When it’s not on board, then these things become part of a political game, and that’s why people don’t get vaccinated.

Should We Be Worried?

KLUTSEY: Interesting. Now, are you worried about conspiracy theories? Is this a threat that we should be concerned about? Or it’s just part of human skepticism about elites and about ideas and about phenomena, and that we should just let it run its course?

DROCHON: I’m more worried about it now than I was when we started this project, this conspiracy and democracy project in Cambridge, which was in 2013. Before this became much more of a politically salient issue with Brexit and Trump and whatever it might be. I am more worried about it now, but I think there’s two realizations.

One was, with all this history and data that we’re doing, that actually it’s just something that’s always been part of our societies. It’s not something that we’re ever going to get rid of. And I don’t think we should ever get rid of it because if you try to suppress it, it’s going to lead us to type of authoritarian or totalitarian societies we don’t want to live in if we want to live in democracies.

And actually, given our studies that we’re doing now in authoritarian regimes, it’s probably more likely to backfire. Especially if you think, if you live in an authoritarian regime, in many ways that’s normal, because the only way you can do politics in an authoritarian regime is conspiratorially because if you do it in the open, that’s not going to work. So you have to do it in secret; you have to do it in that way. It’s part of our societies.

I think it goes back to the question of making that distinction we spoke about between a critical public and a conspiratorial public, and that is the big question. People say, “Well, social media.” It’s like, okay, but social media is here to stay. We need to figure out a way in which, yes, social media seems to encourage this type of thing. Does it lead to more polarization of societies? Probably, but these are things we need to address. We need to figure out these ways of dealing with them rather than suppressing them altogether, which I don’t think is an answer.

On the one hand, it’s there, and I think it’s a challenge of every society in every moment of time to find a way of trying to deal with this. I think we had a slight . . . People talk about, we’re in a post-truth moment. It’s like, yes, but we’ve had loads of post-truth moments before. Let’s not kid ourselves.

We had this Cold War moment, which, okay, people are saying that’s even debatable, like, “Oh, internally there was this desire for truth.” It’s like, yes, but if you talk about the two blocs, the amount of propaganda and conspiracy theories going either way is huge. It was always there. We just felt, “Okay, we have some kind of control over it.” Then we move to the post-Cold War moment, and we have this great moment where people seem to be aligned.

But it’s always been there. The question is, how do you deal with it? How do you deal with it in a democratic way? I would not at all . . . Christopher Hitchens had this nice line, “Conspiracy theories are the exhaust fumes of democracy.” And this is my interpretation of what he meant by it, which is that, well, to have a critical public, there is always going to be the price to pay. There’s going to be conspiracy theories because you can’t really have one without the other.

But the question is, which one is dominating at a moment in time? Maybe in the last while, conspiracy theories have slightly been dominating our political discourse, and we don’t want that. That is a danger to democracy because it doesn’t accept—it’s irrefutable; it doesn’t accept being refuted. It doesn’t accept being taken down. You can’t have a democracy with two sides who just say, “Well, whatever you say is just not true.” You do need a critical democracy where people can engage critically with one another yet still move forward together, and that’s, I think, our challenge right now.

So many answers, I think, to that. There is a question of political leadership. Obviously, there is a question of regulation of social media, but it’s on those things there is a question about. There is also a broader question about socioeconomic questions because people are often drawn to conspiracy theories. Why? Well, going back to the point about exclusion, why? Well, maybe they’ve lost their job. Maybe these things play into it. You’re feeling vulnerable.

There is a question. There’s a broader societal question here. It’s not just about individuals; there’s a broader structural, societal question. But it’s on those questions—political elites, technology, socioeconomic questions—that we need to be working on to ensure that it’s the critical dimension of public discourse that’s dominating rather than the conspiratorial one. I think that’s the challenge for me. But we’re never going to get rid of it, and we shouldn’t try to get rid of it.

Avoiding Conspiratorial Thinking

KLUTSEY: Now, at the individual level, what advice do you have for someone who may be found in places where they are consuming a lot of conspiracy theory and a lot of information? How can they avoid the traps of conspiratorial thinking?

DROCHON: Right. Good question.

KLUTSEY: Maybe it’s the regular scientific-method approach of how you ask questions and you look at empirical data and so on and so forth. But are there some principles, maybe, approaches to help?

DROCHON: Yes. I think there’s quite a bit of, now, media training about asking, “Okay, when you’re looking at sources, is it a reliable source, yes or no?” You see something, don’t just take it as face value. Check it in because there’s more and more fake sources. Like, “Oh, the BBC is saying something.” Then you realize, no, actually that’s not the BBC website. I think there’s a lot of media literacy, which we probably should be teaching more and more to be able to identify when this is reliable, yes or no.

I think there’s one thing that’s interesting, which is that often, people are drawn to conspiracy theories because they feel they’re being critical. They feel like, “Oh, well, this is—I’m being critical of what’s happening, and I’m being intelligent and great. And I’m being critical, and that’s a good thing. I’m critical.”

And it is a good thing. The question I would say there is, are you being critical, or are you just repeating what lots of other people are saying? Because I think the link between, for instance, individual conspiracy theories about 9/11 or whatever, some we’ve spoken about—they’re very highly correlated, often—that means there’s a very strong link between them and the belief in the cabal, the fundamental one.

Conspiracy theories, “I’m asking these questions, I’m being critical” and whatever, and then you ask them—you go a bit further. And often, actually, you end up getting the same thing, which is like, “Oh, there’s a small group of people who control everything.” I think there’s a question, are you being critical? Or actually, are you just saying what a lot other people are saying? Maybe if you want to be critical, maybe you’re better off being critical of them than of just repeating what a lot of other people are saying.

I think that’s something perhaps to keep in mind. We’re saying all these things that’s being critical of government or critical of vaccination, et cetera, et cetera. Okay, great. First there’s a question of media literacy, but then there’s a question that’s like, “Well, so they’re being critical. Great, but what are they saying is happening instead?” If what is being said that’s happening instead—well, it’s always the same story about the small group of people controlling everything. Well, is that really being that critical? And think about that on the individual level. I would add—this wasn’t your question, but I’m just plugging it in.

KLUTSEY: Yes. Go for it.

Building Trust

DROCHON: There’s still—trust is a big question. One of the things that drives conspiracy theories is a lack of trust in public institutions, government, et cetera, et cetera. There remains a degree—trust all levels between family and friends is still relatively high. Even though at the beginning I was saying, have you ever spoken to somebody who will say, “Oh, 9/11 was an inside job, blah, blah, blah”? If you’re actually a good friend of that person, and if they trust you, there’s still a role that you can play there. It’s not at all guaranteed, but it’s worth a shot on an individual level.

It’s difficult. I have friends who were telling me about their own experiences. And they’ll say, “Well, I’ve actually a brother who is going through a bit of a rough patch because of divorce, and he’s really wandering, and he seems to be falling down the rabbit hole.” I was like, “Well, okay. Talk to him and see how it goes.” He’s like, “I’ve tried speaking to him, and I’ve kept tabs.” “How’s all that going?” It’s like, “Oh, it seems to be going a bit better now.” It’s like, “Well, what’s happened?” It’s like, “Well, he got a new job. He’s got a new girlfriend.” [laughs]

Often it’s that, and that’s hard, but you can understand because we’ve all been there. There’s moments where it’s not really going great. If there are friends that are around you and who can—sometimes it’s good not to—you don’t have to directly address, “I think you’re wrong about 9/11 conspiracy theories.” But talk about other stuff around them. “How you getting along with this? Can I help you with this? Can I help you with that?” Accompany them through that. That’s probably—as a friend or family member or whatever, that’s probably the right thing to do because we do know it does—sadly, conspiracy theories do split up families and friendships.

The reason for that is that people are still looking. We all look for a sense of belonging, and conspiracy theory communities can give you a sense of belonging. One of the challenges, I think, is to give people a sense of belonging, whether it being a conspiracy theory community, but there’s loads of ways you could do that. You could be your friends, your hobbies, sports, whatever it might be. Interests in common.

That accompaniment, rather than trying to rationally engage with your friend, but that accompaniment, “Oh, why don’t you come out to the cinema with me?” kind of thing. That’s probably a more useful way of trying to address it than saying, “Look, here’s the facts on 9/11.” That’s more difficult.

Political Criticism

DROCHON: Sometimes you understand where conspiratorial theories come from because the CIA and the FBI have done bad things, right? They have done bad things. Then, so sometimes people think, “Okay, well, the way for me to be critical is to endorse these forms of conspiracy theories.”

There is a link between the two. It’s not like these institutions have been great all the time. Even the people who work within them will be critical. “We messed up here. We shouldn’t have done—the shah in Iran, for instance, that was not good. We didn’t do that. We didn’t—what we did there was wrong, or some of the stuff that maybe we did in Latin America.”

It’s like, okay. Because this was specifically talking about intelligence agencies, since that was the topic, It’s not like they don’t have uncheckered pasts, like most places across the world. Some people feel, especially because intelligence institutions are secretive. The way some have tried to be critical of them is partially to reproduce conspiracy theories.

That goes back to my opening point, which is, okay, is there a way of finding—of being critical of these things? For saying, “No, this is wrong. We don’t agree. We shouldn’t have done this,” et cetera, et cetera, et cetera—being able to express that without using the grammar of conspiracy theories. Being critical without using the grammar of conspiracy theories, that’s the challenge. I can see where certain people seize upon it because it seems like, “Oh, this is the easy way to do it, or this gives me a language to be able to express these criticisms that I have.”

These are shorthands. It’s like, “Okay, I can use this now to express something.” Even if I don’t believe a small group of people control the world, but it allows me to say, “Well, CIA, FBI, whatever, you guys, you messed up sometimes. Here’s my way of expressing that.”

Again, there’s a question there of language. It’s like, okay, can we develop another form of language which is critical without falling into conspiracy theories? That’s part of the parsing out we’re trying to do empirically, is saying, “Well, are these people saying that because it’s politically motivated, or is it because they really believe in conspiracy theories?” There’s a bit of work that needs to be done there.

That exists. That’s one of the questions we have with, was the election stolen? At the moment, how much of that is a real, true conspiracy belief, and how much of it is politically driven? Which if, then, politically that’s left aside, will it drop back down? We say, half of Republicans believe that. Although our studies tend to suggest consistently around 25% of the U.S. population, whether Democrats or Republicans, tend to believe the election is stolen when they lose. But some of that seems to be much more virulent at the moment. Is there more than that 25% because it’s being politically led or not?

KLUTSEY: How consistent has that 25% been over time? Do we go back maybe 10 years, 20 years, 30 or beyond?

DROCHON: Well, what we’ve had definitely goes back to Al Gore. At that point in time, it looked like 24%, 25% of the Democrats thought the election was stolen. I’m not sure we have the data much more beyond that, but there’s no reason to think it’s much more different. Those stories of elections being stolen go back a long way.

On that point, it brings me back actually to what I was trying to say, is that . . . So, this colleague again was saying, “Well, look, what about—there is gerrymandering. There are these things.” Is gerrymandering a form of election stealing? Well, maybe. How do you express that? Oh, of course, you can say gerrymandering; you can say voter suppression. These things do happen.

Then some people say, “Well, the best way to express that is through a form of election stolen because a form of conspiracy theory.” You could see how the link is there. It’s not coming from nothing. But there is a slight difference to saying, “Okay, well, there’s gerrymandering, and this is something that’s bad, and we should combat that,” to saying like it was actually stolen in a conscious kind of way, in the way the conspiracy theory goes.

Then its potential links with the fact that there’s a small group of people in the world who’ve been orchestrating all of this. Finding that distinction and finding the language within which we can make that distinction, I think will probably help us also to make a distinction between a critical public and a conspiratorial public, which, as I’ve repeated ad nauseam now in this interview, it remains the challenge that we have today.

The Future of Conspiracy Theories

KLUTSEY: Wonderful. Now, finally, are you optimistic about the future? I know you mentioned that you’re concerned, given what you’re seeing now. But is there any sense of optimism about whether the role of conspiracy theories in our democracies will decline over time?

DROCHON: Yes, I am. Maybe that’s just me; I’m just optimistic. I think the fact that we’re having all these discussions actually is the starting point because people are now aware of the role that it plays in our societies. If we had had these discussions—when we started the project, for instance, in 2013, nobody was having these discussions. It was this interesting peccadillo, right? That “Oh, you go to the zoo and you look at conspiracy theories” thing. I don’t mean to be derogatory, but that was often how we looked at it.

We’ve moved massively on from that. Now we’re conscious of the fact that it plays a role in our societies. If you look at, even though it remains a very, very small group, QAnon gets a lot of coverage. There’s a slight vicious circle about that because, obviously, they want more coverage. By giving them more coverage, they’re getting what they want. It remains a very, very minority phenomenon in society, more broadly. But people are conscious of the fact that it’s playing a role. We can talk about it. We get a lot more information about it. We know it’s there.

I think a lot of what happened, if you think about the role conspiracy theories played—they did play in both Brexit and Trump. It caught a lot of people by surprise. That surprise element is slightly gone now, and we’re more conscious about it, which means we’re trying to think about ways to combat it. The war in Ukraine actually is a good example of that because it was quite—U.S. government in particular was quite ready for the fact that there was going to be all this propaganda coming from Russia.

They went, “Okay, well. . . .” They had a plan, and it’s like, “Okay, well, what we’re going to do, is we’re actually going . . .” This is very interesting in itself. “We’re going to release all this intel that we have,” where it’s like, Russia’s going to try to do false flag operations as an excuse to invade Ukraine. They’re going to do all these types of things. People have thought about it and were ready.

That’s the starting point. We talk about it; we’re aware of it. We try to devise strategies of dealing with the more nefarious elements of it in terms of Russian propaganda, for instance. We have these strategies. We’ll think about it. We’ll try to find a new balance because I don’t think the point is to get rid of them altogether.

I don’t think—and I hope I haven’t been guilty of this, but I think a lot of people are attracted to conspiracy theories because they’re fed up with people talking down to them. We have to say, there has to be an element of recognizing that this is a part of our societies. We say, “Oh, sometimes it’s very helpful if there’s diseases or whatever, that we accept that this is part of our societies. That we talk about it in an open way.” That’s very helpful for a lot of people.

I wonder whether the same can be said of conspiracy theories, which is no, this is part of our societies. People are attracted to this for these reasons. Well, maybe we need to think about why they’re attracted and what we can do there and be sympathetic also, because I think we all probably go through it. It doesn’t necessarily go all the way to thinking that there’s a cabal rule, something, although that’s sometimes exciting. We could see the attraction.

We need to be sympathetic and understanding and take it from there, rather than just brushing it under the carpet, which we’ve been guilty of for a long time. Yes, there are reasons to be optimistic. There’s a number of different elements in my response there. Yes, probably too many. There are—just the fact that we’re conscious of it and that we’re talking about it. We’re doing podcasts about it. Would we have done podcasts about it five or six years ago? Maybe not, or would’ve not have been as excited. Now you talk about conspiracy. Everyone wants to talk about conspiracy theories.

Even that is a huge step forward. It means that going forward, we can think about, well, why does it happen? What are the bad elements of it? Because there are bad elements of it. Specifically, we know if you’re a conspiracy theorist, you’re more likely to think violence is the answer to social problems. If you looked at what happened on January 6, we know there was conspiracy theories sort of driving elements of that. There are threats there, but we can talk about them now. We’re conscious of it, which means that we can think about the best way to deal with them.

KLUTSEY: Okay. Well, on that sympathetic and optimistic note, thank you, Hugo, for taking the time to talk to us.

DROCHON: Thank you very much for having me on.