Conservatives and Public Health: A Warm Welcome Into a Cold Climate

By Robert Graboyes

In a recent Politico op-ed, “Why Public Health Experts Aren’t Reaching Conservatives on COVID,” University of Chicago professor Harold Pollack insightfully describes how public health’s ideological monoculture impedes the field’s capacity to communicate with conservatives. He proposes a provocative solution for schools of public health: “affirmative action for conservatives, starting now.” Though well-intentioned, his proposal is untenable, because there’s no reason to believe that the bulk of his colleagues would welcome or even tolerate the diversity of thought that Pollack seeks.

Pollack, a self-described “emphatic liberal Democrat,” warns that COVID-19 vaccination efforts are lagging in part because “the people spreading the message about the Covid vaccine”—that is, public health professionals—“don’t look or sound much like the people who need to heed this message.” If so, their rhetorical inadequacies are a lethal failing.

Pollack sees few conservatives in his classes and offers, “If someone applies to our school who was (say) president of University of Texas Students for Life—I want her in my classroom. I want progressive students to present, defend, refine and improve their arguments knowing that a peer who disagrees with them is right there, ready to engage.”

(By the way, it seems clear that the “conservative” students missing from Pollack’s classes must include libertarians, classical liberals and other not-exactly-conservatives—that is, anyone who might vigorously challenge progressive classmates.)

He recognizes the challenge that awaits his targets. In today’s classes, they will experience “palpable absolutism and lazy groupthink among progressives.” In applying for jobs, they will experience discrimination, even if the quality of their work is equal to that of their left-leaning classmates. Years of study and mountains of tuition may buy only a gig as sparring partner for progressive classmates, followed by cold shoulders in a hostile employment market.

Why, then, would any conservative student accept Pollack’s well-meaning invitation?

What We’ve Got Here Is Failure to Communicate

Pollack writes, “Surveys show that the Americans dug in against the vaccine skew decidedly conservative.” Indeed, there is a loud chorus of anti-vaccine sentiment on the right—especially among more strident media and social media voices. But there are other vaccine-hesitant population segments, and the data do not conclusively demonstrate that Republicans are the most hesitant demographic (though they may well be so).

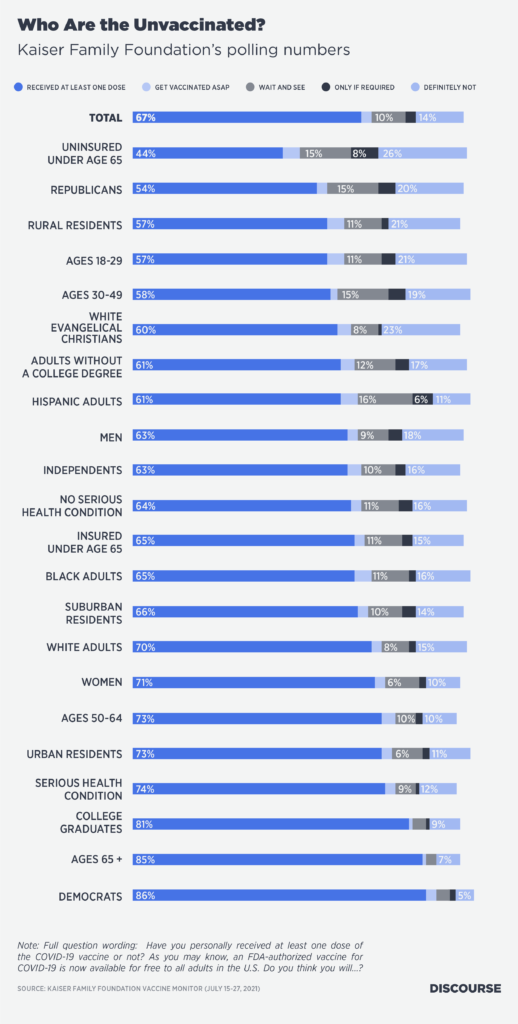

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) polls Americans about vaccination rates and about attitudes among the unvaccinated. Its most recent polling (shown in the accompanying figure) indicates considerable vaccine hesitancy among Republicans, though the polling failures of recent years lead me to suspect that KFF’s numbers may exaggerate the differences between Republicans and other groups, including younger people (18-49), rural residents, Hispanic Americans and African Americans.

Taking KFF’s numbers at face value, in July, 54% of Republicans had received at least one vaccine dose, versus 57% for rural residents and those ages 18-29 and 58% for those ages 30-49. Not much difference among those groupings. Slightly higher vaccination rates are found for Hispanic American adults at 61%, political independents at 63% and African American adults at 65%.

According to KFF’s methodology, however, all these groups are in the same ballpark, statistically. For Republicans, African Americans and Hispanic Americans, for example, the statistical margin of error is a sizable 7 percentage points in either direction. So, statistically, Republicans could really be at 61% and African American adults at 58%. And even those numbers assume that KFF’s pollster was working from a sample that is representative of the general population (or adjusted to simulate a representative sample). But that assumption is dicey. A 2019 Pew Research Center report warned of inherent sampling errors and biases in telephone polls such as the one KFF used. (Many pollsters, including Pew, have shifted away from telephone polls for these reasons.)

But present-day American polling in general has a chronic, critical problem: A sizable percentage of conservatives either refuse to respond to pollsters or mask their beliefs when they do. After the November 2020 elections, Charles Blahous and I explored this phenomenon. The 2020 preelection polls indicated a “blue wave,” with Joe Biden easily beating Donald Trump and Democrats making strong gains in the House and Senate. Instead, Biden squeaked by, Democrats gained their precarious grip on the Senate only after Georgia’s January runoffs, and Republicans gained 15 House seats.

My guess is that the Republicans willing to express their opinions to KFF’s pollsters are likely to be those most adamantly anti-vaccination. If that’s correct, the vaccination gap between Republicans and some of these other groups may actually range from small to nonexistent. Moreover, “Republicans” is not the same as the amalgam of conservatives plus libertarians plus other nonprogressives apparently absent from Pollack’s classes; among this wider group, vaccination rates may be even higher.

Casual observation and opinion polling suggest that conservatives are more vaccine-resistant than other groups—and they probably are. But KFF’s statistics, like other poll results making the rounds, simply aren’t robust enough to make a strong case that public health is enjoying significantly greater success with rural residents, younger Americans, Hispanic adults, African American adults and other groups. Public health professionals don’t “look or sound much like” a sizable chunk of the American public—and that extends well beyond conservatives alone.

A Brief Disclaimer

In judging this essay, it may help readers to know that I’m not one of public health’s “problem cases.” I’m fully vaccinated and wish everyone were. My views don’t fit squarely with those of contemporary progressives, liberals, conservatives or libertarians. If I must bear an ideological label, “classical liberal,” as described by legal scholar Richard Epstein, bothers me least. My ambivalence toward public health academicians doesn’t blind me to the field’s great accomplishments. I have celebrated public health’s eradication of smallpox as one of the 20th century’s most impressive public-sector achievements, along with the Manhattan Project, Project Apollo, Arpanet and the Human Genome Project.

In 2017, as Pollack observes, “House Republicans passed a conspicuously shoddy bill to repeal and replace Obamacare,” which “politically self-immolated once it faced real scrutiny.” I criticized that bill at the time, and Speaker Nancy Pelosi quoted my words favorably in a press conference at the Capitol. In a satirical 2014 Politico essay, I portrayed liberals as making ludicrously utopian promises about healthcare and conservatives as responding with plodding, incoherent word salad. Those dynamics have not abated on Capitol Hill.

No Dissent Please, We’re Public Health

Pollack says, “The palpable lack of conservative students, scholars and thinkers within the main academic institutions that train our public health and social service workforce should be obvious to everyone in the field,” and “many of our students do not have—may never have had—the experience of being openly challenged by conservative peers in our classrooms.”

Perhaps there are good reasons why such challenges seem rare. Alex E. Woodruff, a health science specialist at Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, describes his experience at Boston University:

When I began my graduate degree in public health policy, I expected debate to be valued by my fellow students. Unfortunately, I was wrong. . . . There is a culture on campus of “us versus them” that suppresses healthy discussions in class. I have tried to spark conversations by playing devil’s advocate—arguing pro-business, pro-capitalism, and pro-religious expression. An uncomfortable silence falls over the classroom. This silence is a pillar of groupthink. It is a subtle but powerful influence that discourages students from thinking independently. Missed opportunities for students to explore ideas is the cost of letting this conformity persist.

I don’t doubt that an openly conservative student entering Pollack’s class would receive a warm welcome and fair treatment. But Pollack’s description of his colleagues is deeply unsettling:

I fear that many struggle to distinguish truly unworthy arguments presented by some conservatives—say, prevarication about climate change, or denying the Republican Party’s long history of voter suppression and appeals to white racism—from more worthy and serious arguments presented by conservatives that everyone should learn from and address.

This is a breathtaking indictment of the public health professoriat. The colleagues Pollack describes hear an unsavory argument from some conservatives and leap to two conclusions: First, they apparently assume that all conservatives (and libertarians, classical liberals, etc.) must uniformly agree with the argument they’ve heard. Second, they have difficulty comprehending that an individual can be foolish on one topic and wise on others—or the fact that this is true of most of us. The need to “struggle” with such elementary concepts betrays ignorance of or contempt for basic human nature and tenets of tolerance revered since the Enlightenment. Such incognizance raises serious questions about these professors’ capacity for scientific reasoning.

No parcel of America’s political landscape is devoid of contemptible ideas. I taught over 2,000 students who supported candidates all over the political playing field: Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Bernie Sanders, Donald Trump, Ron Paul and more. I assumed every student had positive contributions to make. None ever failed to do so.

Pollack’s words also touch on public health’s long-standing irredentist tendency to seek dominion over fields where public health scholars have ample biases and no particular expertise. Climate change, political parties, voting laws and racism are all worthy topics for discussion and debate. But on these subjects, public health scholars are no better informed than late-night barstool pundits. As they stretch the definition of “public health” to encompass whichever hot-button issues strike their fancy, they shed credibility and powers of persuasion.

In The Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf criticizes the hundreds of public health practitioners who trumpeted a credibility-damaging “ideological double standard on protests” during the COVID-19 pandemic. They simultaneously called for mass political marches for favored causes while roundly condemning nonfavored events as superspreader menaces to public safety. Politicizing public health, Friedersdorf wrote, means that “more Americans will decline to heed any public-health advice or journalism, seeing it as ideological and hypocritical.”

Pollack demonstrates unusual open-mindedness in his field by praising former President Bush:

George W. Bush saved millions of lives around the world through the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)—a program we might well emulate in vaccinating the world against Covid; liberal students would be well-served by appreciating the impact of the Christian conservatives who helped drive the effort.

Bush may indeed have been the most prescient and proactive of recent presidents on the risk of pandemics like COVID-19, and praise for Bush has flowered among some liberals recently. But a student offering such thoughts while Bush was in office would have courted pariah status among professors and classmates in public health.

In 2011, Nobel Prize-winning economist and self-described “liberal and progressive” opinion columnist Paul Krugman opined that “a liberal can talk coherently about what the conservative view is because people like me actually do listen. We don’t think it’s right, but we pay enough attention to see what the other person is trying to get at. The reverse is not true.” In “The Ideological Turing Test,” George Mason University professor and Mercatus Center scholar Bryan Caplan contended that Krugman had things completely backward and offered Krugman a way of testing their respective theses. Speaking of his fellow libertarians, Caplan says, “We learn [Krugman’s] worldview as part of the curriculum. He learns ours in his spare time—if he chooses to spare it.” Unlike Krugman, Pollack knows his field has a problem, and, to his great credit, he’d like to change that.

Public Health’s Checkered History and Habits

As we’ve seen throughout COVID-19, public health professionals can be self-sacrificing godsends. They’ve saved countless lives through contact-tracing and arm-jabbing. It’s impossible to overstate the significance of John Snow’s work on London’s 1854 cholera outbreak. One could populate a menagerie with once-terrifying infectious diseases now largely forgotten thanks to public health’s triumphs. (One of my wife’s treasured childhood memories is a hug from her family’s neighbor, Jonas Salk, after he announced his polio vaccine.)

But public health has always had dark undercurrents—a tendency to engage in draconian social engineering, often poorly informed, cocksure and masked in scientific trappings. Pollack says conservatives are “probably more scarce today [in public health] than any time I can remember.” Perhaps this increasing scarcity reflects an increasingly politicized, insular and intolerant field.

I’m deeply thankful for vaccines and have long worried about declining vaccination rates for diseases such as measles. But public health also willingly participated in multiple atrocious 20th-century abuses. In 1927, the Supreme Court’s decision in Buck v. Bell put the muscle of government behind the pseudoscience of eugenics, resulting in the forced sterilizations of tens of thousands of Americans. In perhaps the most monstrous sentence in Supreme Court history, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, “The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.” Afterward, for decades, public health officials were complicit in rounding up Americans, spuriously branding them as “feebleminded,” imprisoning them in mental institutions and applying surgical knives to destroy their lives. (The story is told hauntingly in a documentary called “The Lynchburg Story.”)

Legal historian Paul Lombardo has documented how, in the interest of “population health,” 20th-century public health was complicit not only in forced sterilizations, but also in bans on interracial marriage, bans on marriage between disabled Americans and deportations of immigrants who failed spurious IQ tests. For forty years, the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control conducted the horrific Tuskegee syphilis study on African American men. The common thread is that public health officials have been willing to exert damaging control over individuals in the name of collective goals and to feign authority in areas where they are mere dilettantes.

As of 2021, the public health sector—which, by Pollack’s description, is incompetent to communicate with half the American population about its core expertise (the spread of infectious disease)—has sought to claim manifest destiny over climate change, property law, racism, wages, voting laws, transportation, terrorism, crime, policing, juvenile justice, higher education, employment, incarceration, financial lending, identity theft, bullying, gentrification, human trafficking, online poker and who knows what else.

Professor Pollack would invite conservatives into his classroom to help his profession better understand a broad swath of the American population. He deserves kudos for recognizing the problem and seeking a remedy. To his credit, he has sternly lectured his colleagues in this area over the years. But he describes a troubled and troubling professoriat, flouting or ignorant of liberal principles. The characteristics he describes are not mere rhetorical shortcomings. They are symptoms of profound anti-intellectual rot.

Sincere thanks to Dr. Pollack. But before asking conservative students to help heal what ails public health, the field first needs to examine itself and ponder deeply the words of Luke 4:23: “Physician, heal thyself.”