Command of the Seafloor Is the New Naval Challenge

Acts of sabotage against undersea infrastructure are becoming more frequent and costly

As the U.S. Navy struggles to catch up with the People’s Republic of China’s rapid expansion as a growing maritime power, yet another frontier must be added to its responsibility for the ocean’s surface, subsurface and the sky above them. A vast undersea infrastructure, spanning the world in the form of telecommunications cables and resource pipelines, for the most part lies unmonitored and unprotected on the ocean floor. Increasingly, these assets are coming under attack.

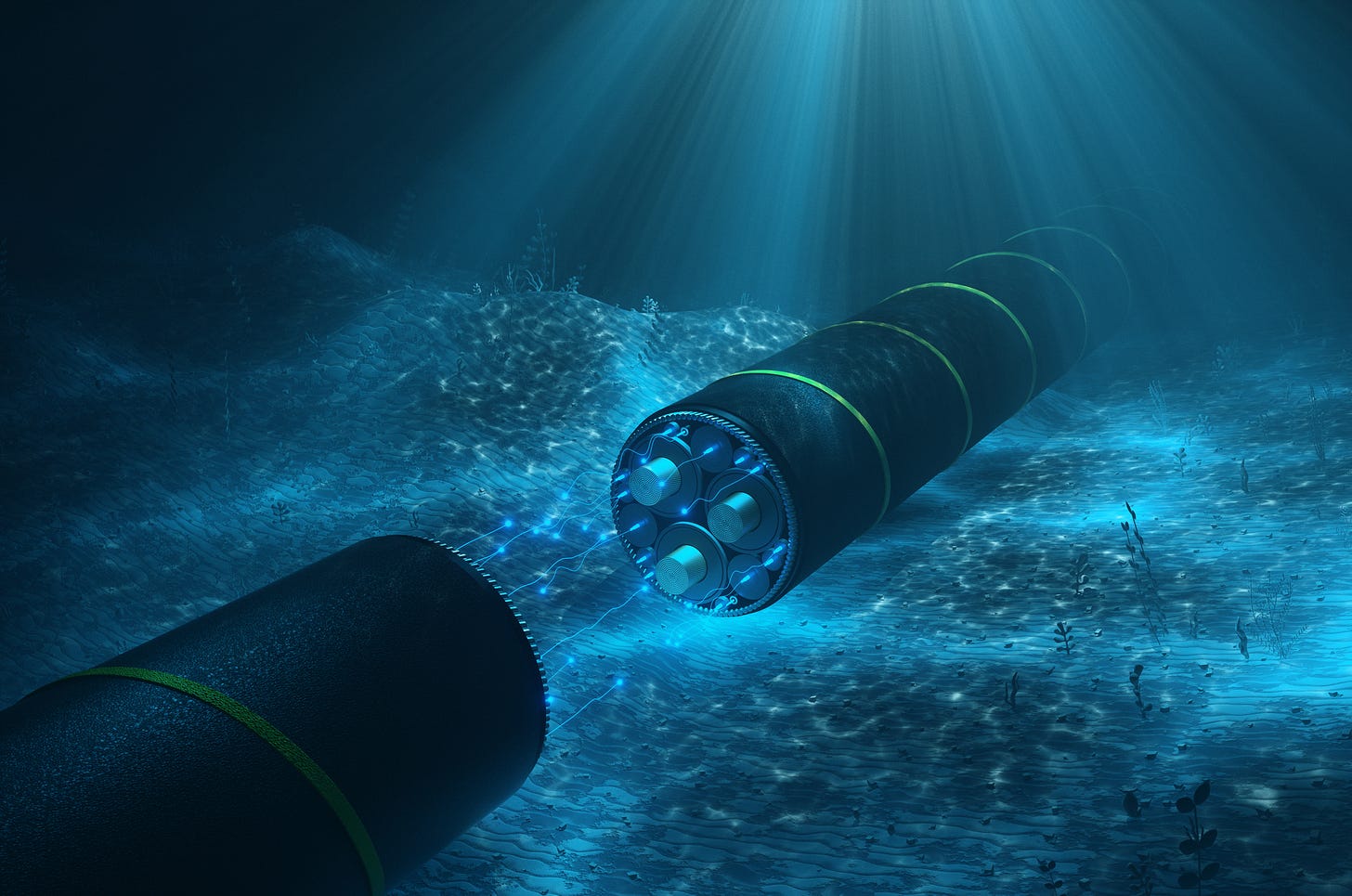

Undersea fiber-optic cables have become the backbone of the global communications network. A report from the U.S. Naval Institute says about 97% of intercontinental communications carrying $10 trillion in transactions daily occur via undersea cables, with satellites picking up the balance. Meanwhile, about 20,000 miles of undersea pipelines carry huge volumes of natural gas and oil.

Just as satellites are no longer protected by virtue of their location in low-Earth orbit, underwater cables and pipelines are no longer safe in the deep. Infrastructure on the floor of relatively shallow seas and coastal waters is within reach of nonspecialist vessels, such as merchant transports dragging anchor chains. And increasingly, swaths of the ocean depths are coming within the range of specialist submarines and surface vessels operating deep-diving manned and unmanned submersibles.

In other words, the means for damaging undersea infrastructure are becoming more widely available. China has reportedly patented an anchor design for cutting cables, potentially turning any vessel of its vast merchant marine into a seafloor predator. Private builders and operators of deep ocean submersibles are proliferating. As undersea cables and pipelines come within reach, political expediency becomes the deciding factor in whether a hostile power will choose to attack them. And recent history has shown that sabotage of undersea infrastructure carries little if any blowback for its perpetrators.

Gray War in the Deep

Samuel Byers, senior national security adviser at the Center for Maritime Strategy, said the importance of undersea assets to commerce, civil life and the military is increasing just as the complexity and expense of reaching those assets is coming down.

“What you once needed a billion-dollar submarine for can now be accomplished with an operation you can put together for a hundred million dollars or so,” Byers said, specifically citing the destruction of the Nord Stream natural gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea in 2022. The pipelines enabled the sale of Russian natural gas to Germany. Investigations point to possible covert action by Ukraine to forestall Russia, but sabotage has not been conclusively proven.

In addition, a number of telecommunications cables have been severed in the Baltic, either accidentally or on purpose. Several Chinese merchant vessels, possibly acting on behalf of Russia, have emerged as suspects. On the other side of the world, Chinese commercial and military ships are also suspected of cutting cables near Taiwan. China says all such incidents are due to either common maritime accidents or the naturally harsh conditions on the sea bottom.

If it is possible to sabotage pipelines and fiber-optic cables in some of the world’s most heavily traveled waters with impunity, then the entirety of the world’s undersea infrastructure is at risk.

“We don’t have clear visibility on particularly critical segments of undersea infrastructure, like junctions or nodes where cables and pipelines come together,” Byers said. “On top of that, there is a level of deniability that is not possible in a lot of other ways that a state could pursue aggression.”

At the outbreak of World War I, Great Britain cut Imperial Germany’s transatlantic undersea cables, restricting the latter’s ability to communicate outside mainland Europe. Germany came to rely on the cables of neutrals, including the United States. Ironically, the infamous Zimmermann Telegram, seeking a German compact with Mexico in the event of war with the U.S., was sent encoded over U.S. cables. British intelligence secretly intercepted and decoded the message and found a roundabout way to alert Washington, thereby (along with other factors) inducing America to join the Allies.

Messing with the enemy’s communications infrastructure has a long and proud tradition. Cable-cutting exploits featured in the Spanish-American War of 1898. A relatively new wrinkle is damaging or even destroying undersea infrastructure without a declaration of war.

Historically, other nations’ property has not been automatically sacrosanct in times of peace. U.S. military and intelligence services engaged in a long campaign of cable-tapping and listening in on Soviet undersea cables throughout the Cold War. However, the purpose of these operations was to gather intelligence without being detected, so the targeted infrastructure remained fully functional. To accomplish this, would-be eavesdroppers had to build or convert submarines carrying specialist diving crews to operate in harsh underwater conditions of extreme depth, dark and cold.

The rewards for tapping a rival’s cable outside wartime were arguably worth the expense and risk of discovery, but sabotaging these cables—or, worse, pipelines carrying strategic resources—during the Cold War would likely have become a major incident. However, the end of the superpower confrontations of the 20th century has made would-be vandals of undersea infrastructure more willing to take the risk. Given the deliberate, legalistic approach to investigations of suspected sabotage, where conclusive proof is hard to come by, the rate of such incidents can only be expected to rise.

Everywhere, All at Once

Deterring saboteurs or catching them in the act is hard because Western navies in particular are already stretched to the point of breaking down with ongoing assignments. In the U.S. Navy, deployments are extended to cover trouble spots such as the Red Sea and flare-ups in the Middle East. Allied ships are not available or not capable of participating to any useful degree. Routine “show the flag” deployments by European allies draw American grumbling that the ships could be more usefully engaged closer to home. European patrols against Houthi attacks in the Red Sea are practically nonexistent.

Even the U.S. Navy, now the world’s second-largest fleet, doesn’t have enough hulls to cover existing responsibilities due to misguided procurement programs and anemic shipbuilding and maintenance capabilities. It is hardly in a position to assert dominance over the seafloor, which is evolving into a new theater of war nearly as remote, vast and technically complex as near-Earth orbit.

The problem, as maritime strategist Byers sees it, is that while the Navy is the most logical service to respond to undersea challenges, it is getting the job without a commensurate increase in funding to accomplish it. This means the Navy must either compromise its other priorities or seek other solutions.

“The scale of the undersea infrastructure problem has leadership demanding that the Navy protect it now,” Byers said. “That’s fine. But what are we going to do less of? Are you going to ask us to do less power projection? Because that’s where our money goes. And right now, there aren’t enough aircraft carriers to provide a constant presence in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Western Pacific. When the political leadership asks for a carrier strike group to support a combat command ashore—like they have done repeatedly over the last year and a half in the Middle East—they get mad if the Navy isn’t able to do that immediately. And now they also want us to be responsible for all this stuff on the bottom of the ocean?”

In short: Which missions is the leadership going to allow to fail in order to protect the seafloor? The answer, of course, is none of them. Byers points out that the Navy has already vastly increased the amount of money it has allocated for building submarines, which are earmarked for supporting carrier battle groups and other sea control missions and can’t be expected to monitor fiber-optic cable junctions.

Submarine acquisition and shipbuilding in general have become national priorities, and money is being made available to achieve them. At the same time, it is the nature of evolving threats that new priorities arise without a commensurate budget increase.

“Naval powers in general have to worry about things like protecting undersea infrastructure and policing fishing fleets,” Byers said, adding that the generally low priority of the threat means it can be done in concert with other activities. However, the threat is changing: “Facing China, you now have their huge merchant fleet, which is turning into a maritime militia, not to forget the malign activities from their fishing fleet.”

Ultimately, all of China’s shipping must be regarded as an adjunct of military operations, which are ongoing in one form or another even in times of nominal peace.

Hoist the Black Flag?

Writing in the Center for Maritime Strategy’s online journal, national security analyst Mike Daum reports that, according to U.S. officials, Chinese vessels are conducting espionage operations on undersea cables to identify vulnerable U.S. military communication links. Furthermore, he says Russia is particularly focused on honing its ability to target critical undersea infrastructure during a crisis.

Daum writes, “The limited capacity of U.S. and allied fleets cannot safeguard the approximately 750,000 miles of undersea cables around the globe. Allocating more ships, whether through the Navy or the Coast Guard, is only a piecemeal approach to addressing the threat. Instead, policymakers should lean into American innovation to meet the challenge.”

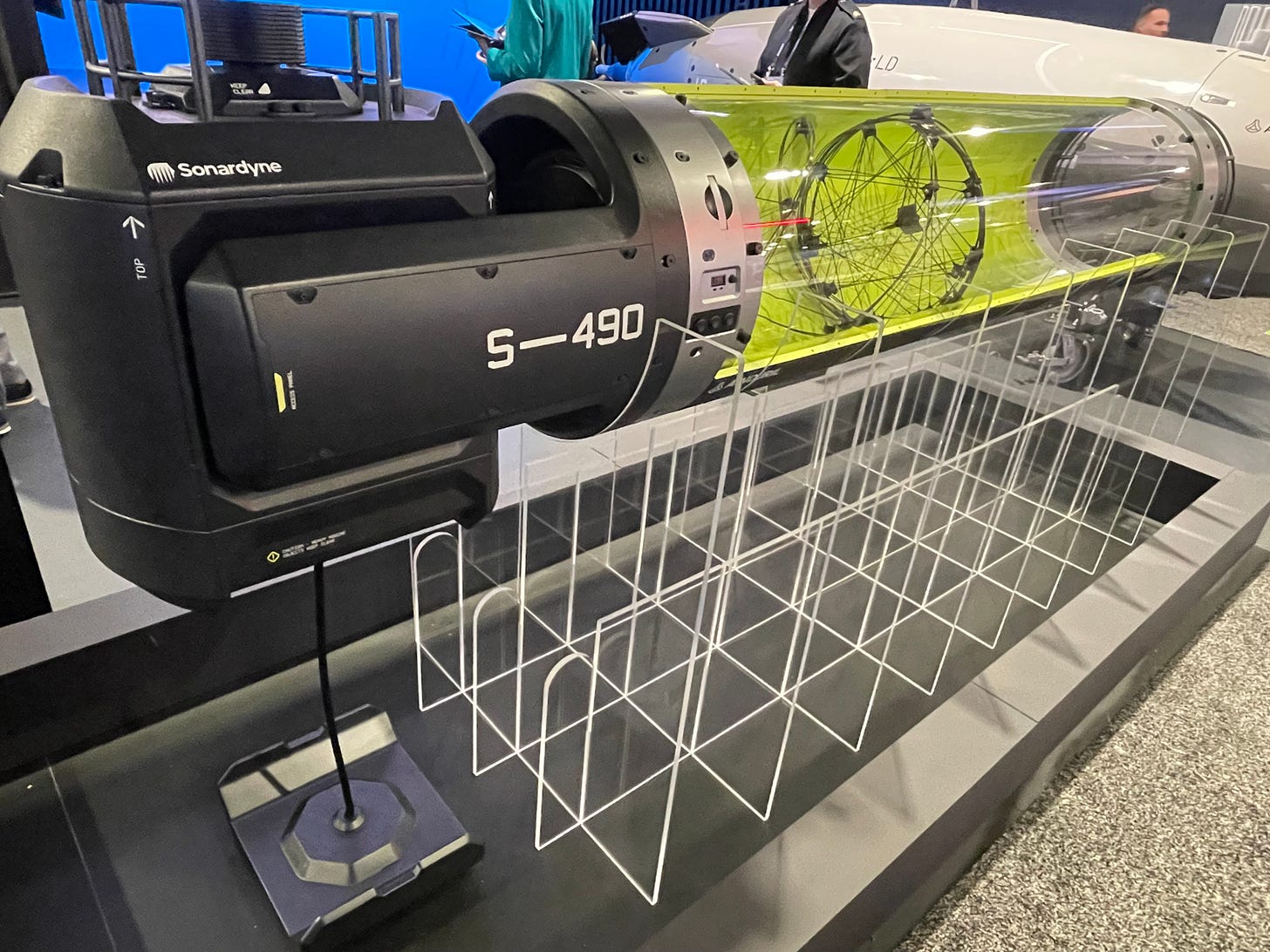

In this age, it should not be surprising that much of the looked-for innovation is in the form of unmanned air, surface and submersible systems that can conduct patrols and persistently monitor infrastructure. At the Sea-Air-Space 2025 naval technology exhibition in Maryland last spring, a number of contractors were showcasing equipment for improving “domain awareness” of the seafloor.

For example, California-based newcomer Anduril Industries showed its Dive-LD and Dive-XL autonomous underwater vehicles, designed for long-endurance patrols of coastal and deep ocean regions, with the XL model being larger and more capable. Both systems have a variety of internal sensors. The Dive-XL is able to deploy the company’s Seabed Sentry sensors, which can provide optical and acoustic monitoring of underwater infrastructure while being unattended for months or even years at a time.

While unmanned systems may help extend coverage of seas where hostile saboteurs are suspected, the oceans are more expansive than any number of systems and sensors can monitor. At best, the U.S. and its allies may be able to focus on choke points where multiple cables or pipelines come together, such as the Malacca Strait near Singapore and the Bab-el-Mandeb between Yemen and Djibouti. However, the watchers can’t be everywhere, and crafty saboteurs will always find an opportunity to inflict damage.

Russia has created a so-called shadow fleet of tankers and cargo vessels to move oil and other resources in a bid to evade sanctions imposed after its invasion of Ukraine in 2022. At least one of these vessels is now suspected of conducting covert cable-cutting operations. The fear is that a desperate Russia may turn to such “hybrid war” techniques as a means of pushing back against Western opposition to its hot war in Ukraine. On top of this threat is the aforementioned possibility that China will use its extensive merchant marine to undertake similar operations, either against Taiwan or in support of its Russian ally.

For this reason, some have floated the idea of bringing back letters of marque and reprisal, authorizing owners of private vessels to essentially hunt pirates and other illegal operators on the high seas. While most nations have eschewed the concept of privateers, the U.S. has never formally relinquished its right to make that designation. In practice, the closest thing to a privateer today is a private security guard aboard a commercial vessel. If hostile nations are surreptitiously using commercial vessels to inflict damage on Western infrastructure, however, then the concept of deputizing an armed naval auxiliary could become more attractive.

Of course, what is amusing as a thought experiment is in the real world fraught with danger, explosive diplomacy and the potential for military escalation. If one of China’s cable-cutting or pipeline-breaching vessels is seized, whether by uniformed forces or privateers, the PRC will likely retaliate with its significant navy.

Perhaps the only effective way to deter sabotage of undersea infrastructure is not to allow it to become normalized in the first place. Consider the internet, another example of international infrastructure that has become vital to the global economy and is regularly used as a conduit for attack by rival countries and affiliated groups. In the cyber domain, the West seems resigned to suffer hacker incursions and data breaches conducted by agents of Russia and China without any obvious repercussions. We hear of the breaches but next to nothing about official responses or retaliation. No amount of cybersecurity seems able to prevent the breaches.

Likewise, it is not possible to guard every stretch of underwater cable or pipeline all the time. This being the case, nations that rely on this infrastructure have to be willing to retaliate in other venues. The offending countries must have other chips on the table that they value. You don’t necessarily have to destroy something in response. Cut a cable, get a 5% tariff. Blow up a pipeline, lose your airline landing rights.

Tit for tat, in a modified form, may be the best way to keep undersea infrastructure safe.