Clicking Our Way Down Main Street

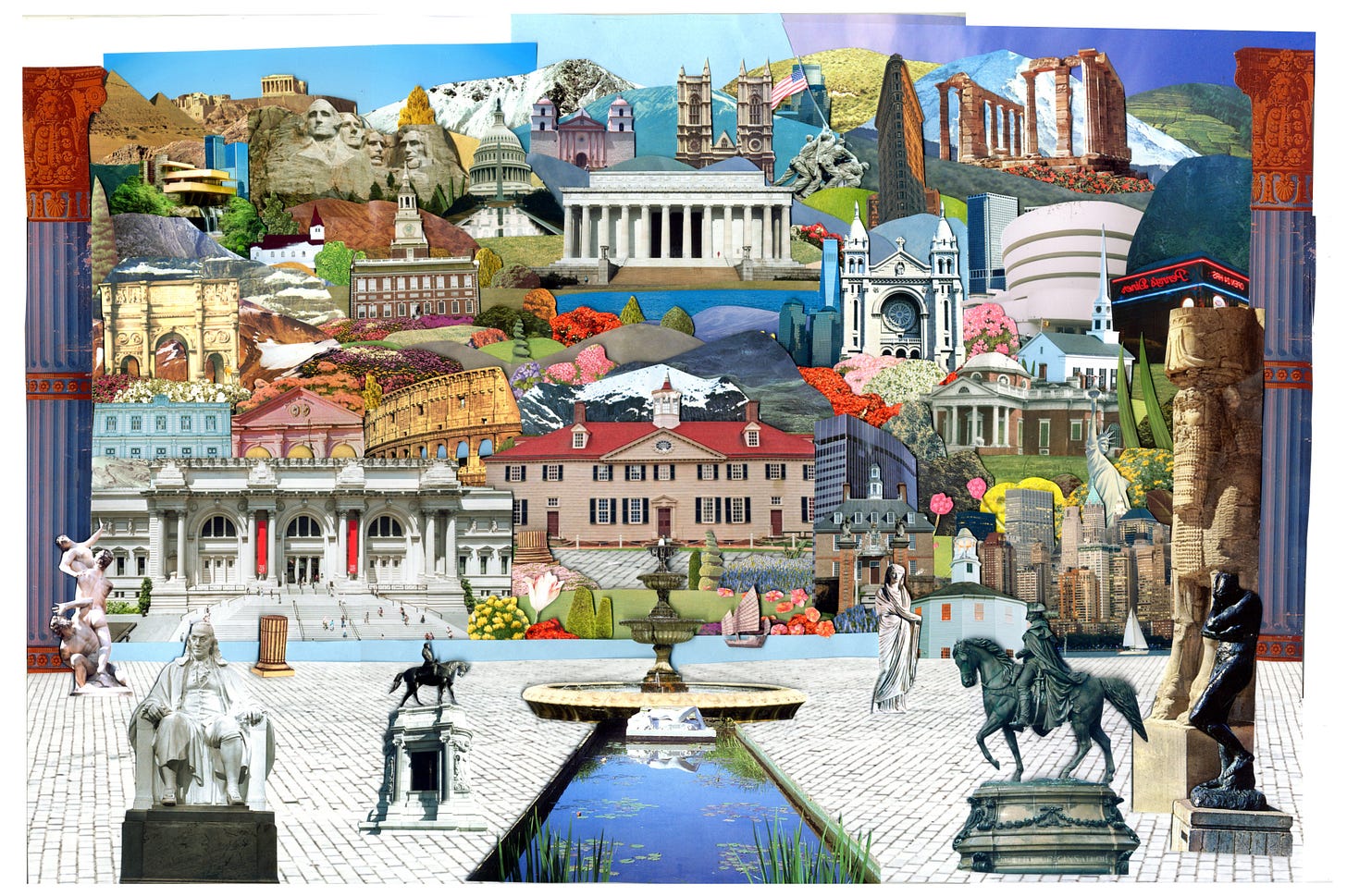

A virtual record of American urban history lets us take fascinating, depressing but possibly hopeful trips through America’s downtowns

By James Lileks

The greatest cartographical inventions of the 21st century are the Webb telescope and Google Street View. The first peers into distant realms and notes the initial faint stirrings of a newborn star. The second looks into an antiques store in a small town and picks up a detail on the door handle that tells you it used to be a Woolworth.

If I had to choose which one I’d study for the rest of my days, it would be the fruit of the ever-roaming Google cars. Yes, yes, the Webb produces pictures of wonder and beauty, as well as knowledge about the cosmos we inhabit. But there’s something about a small-town movie marquee, a faded painted sign for Coca-Cola, or a proud little building in a two-block burg with the owner’s name on it engraved in stone. Google has given us—for free!—the most extensive record of American urban history ever created, and it’s endlessly fascinating.

And unutterably depressing. Sometimes.

For years I’ve been picking out towns at random and touring the main streets, one click at a time. A town that was once just a dot on a map now becomes a place you can interrogate and explore. But for town after town, county after county, state after state, you ask: What happened? Why does it look as if someone rolled a neutron bomb down half the main drags in America? Why are the second-floor windows boarded up, as if they feared a plague of zombies on stilts?

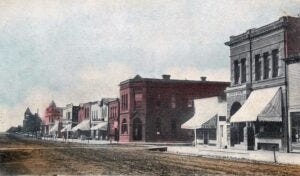

Google Street View teaches an interesting lesson: There is a sameness to American small-town main streets, and an infinite diversity in the details. The buildings are drawn from the same cast of characters.

The 19th–early 20th century building. The plain two-story store with decorative brickwork, for example. A modest classical ornament ordered from a supply house back east sits on the cornice, an improbable survivor of a century of withering weather. And there’s a bank, always on the corner. Many were done in the Richardsonian Romanesque style, with rusticated stone and squat pillars. Subsequent opinion would regard the style as ponderous and unsightly, as if the building had developed a horrible dermatological condition. They’re never banks today, having foundered in the Panic of ’97, when someone tried to corner the tin market, or something. You never know. You just see BANK carved on the wall and hope the farmers were made good in the end, but probably not.

A small town usually has an imposing monument to civil society and human companionship. Masonic halls, Independent Order of Odd Fellows buildings, opera houses. These can be three stories or even four. Ornate details show off the organization’s prosperity. The opera houses, you suspect, were not putting on “Rigoletto” on a regular basis. They were signs the town had come of age and could provide culture to the locals. You know there are still signs of the building’s previous purpose behind the boarded windows. A stenciled illustration on a wall, an empty socket where a bulb illuminated the proscenium, marks on the floors where the seats were bolted. You imagine it’s packed with stuff no one wants and passes each year undisturbed, waiting for the town to come back. Waiting for the people to come back.

The ’20s had two styles, more or less: Plain and Roman. The former was the “Commercial” style, characterized by red brick and light stone accents. It scales well: It could be a modest two-story structure with shops on the bottom and offices or apartments upstairs; it could be an eight-story office block or hotel. If it was a hotel, it was the most modern in the state, of course, absolutely fireproof, with phones and hot water. If it is still put to use today, it’s always senior housing. The people who were kids and saw the hotel as a place of mystery and excitement—all those people coming and going, the trips to the barbershop on a Saturday, the stories in the newspaper about the dinners and events held in the ballroom—those people are now living inside, looking out, custodians of the bygone days.

The Roman style was reserved for banks and post offices. They look like embassies of the Empire dropped down in Iowa or Georgia. Fluted columns hold up sober pediments; a stone eagle may have alighted over the door. The name of the establishment is carved in the facade. It all says Permanence and Stability. (The 19th century bank down the street would like to have a word about that.)

The ’30s. This is the rarest of styles, for obvious reasons. Some cities may have prospered during the Depression, thanks to a local commodity that insulated them from the worst, and a local businessman erected a structure in the latest style to show off his progressive tastes. Streamlined, with a rounded corner. Moderne details, perhaps an Art Deco chevron ordered from a catalog. More often, the sole sign there were any additions downtown at all was a post office or WPA-built public building, spare but futuristic. Compared to the Roman banks, it was like Buck Rogers’ barracks.

The post-war buildings are few. They’re mostly banks. The ’50s and ’60s banks are grey-flannel-suit boxes with a few International Style touches. The banks of the late ’60s hail from the confused era of Baroque modernism, with decorative columns that flair at the top. The banks of the ’70s are awful things, boxy and brown with thin windows, if they have windows at all.

That’s what you’ll find in one town after the other. What you won’t find, alas, are tenants. Or signs.

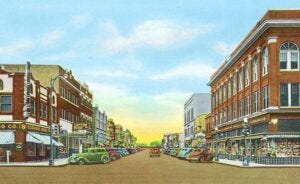

The shiny postcards of small towns in the ’50s and ’60s usually show the main street bristling with signage jutting out from the stores at perpendicular angles, jostling with one another to blare out the come-ons. Sometimes the postcard scene was set at night to highlight the glorious neon. So many hand-bent tubes filled with glamorous gas—why, if you held the card up to your ear, you could almost hear the low constant buzz of the sign. Some of the signs were mass-produced, standardized, the same from town to town: the rich red-and-gold livery of the Woolworth, the orange-and-blue Rexall sign. But most of the signs were one of a kind, made for the store, commissioned by a fellow who was going to make sure his name clicked on at twilight and burned its brand in the dark.

Now you look at the same street on Google, and the signs are mostly gone. If they remain, the tubes are busted, the paint peeled—unless the business, which always seems to be a jeweler, is hanging on. You’re more likely to find trees than signs. As small-town retail began to wither, the city leaders tried to make the streets more attractive. Planters and benches, and trees. That’ll bring ’em back. That’ll keep ’em from driving to the big town with the mall. Trees. Now the trees obscure the facades, and it looks as if the town had been abandoned to nature.

If you peer through the branches, you can find the bolts in the old brick where the signs were once anchored. They might have removed it because the mortar was old, and the sign was in danger of dislodging. (The same fear led building owners to shave the cornices, lest some old stone fall.) The city might have banned the signage, prompted by a national “beautification” movement that tut-tutted at crass commercial come-ons. Billboards were ugly; signs were kitsch. The night street dimmed and never woke up again.

After World War II, downtowns looked tired, out-of-date. On the other side of the Depression and an exhausting global conflict, people were interested in something up to date, something modern that said their town wasn’t a backwater burg but part of the post-war order. Rockets and interstates, new styles, new things to buy, new ways to sell them. The surest way to update a downtown wasn’t knocking down the Johnson Block, but sheathing its upper floors in sheet metal. Often the store’s name was affixed to the metal, and if the town was lucky, Bob’s Bootery or the Town Toggery would backlight the sign.

But that wasn’t enough. The ground floor would be modernized. New light-colored thin brick, or veneers that looked like Flintstone boulders. Conical lighting fixtures that reminded you of spaceship rocket nozzles. Main Street dressed itself for a prosperous new era, and for a while, it worked. But it didn’t last. Town after town, county after county, state after state—the Google Street View cars record one tumbleweed town after the other. The Woolworth might be occupied by an antiques store now, and that’s the saddest fate. All the accumulated possessions of the previous generations, all the stuff the kids got out of the farmhouse after Mom died, all the stuff people bought at Woolworth—it ended up back here in a quiet store that makes just enough to keep the lights on.

Again, you ask: What happened? So much happened. More cars and better roads helped the larger burgs consolidate their commercial cores. If a Walmart was erected a half-hour drive away, it could squash a small-town main street like an elephant sitting on an ant: nothing personal, didn’t even notice you were there, frankly. A factory closes when the owners offshore. The sons and daughters move to the city. Add internet shopping to ensure nothing filled the empty storefronts. Downtown’s dead, save for a bar and an antiques store for big-city day trippers passing through to pick the bones.

But is Downtown’s future hopeless? No.

I was born and raised in Fargo, North Dakota. When I was growing up, downtown was bustling, vital, packed with stores, alive with signage and neon. I still remember the animated sign of a bartender working a cocktail shaker hanging off the Five Spot bar. Four department stores, hotels, barbershops with illuminated poles. Big bank signs in the sky staking out their territory: the M for Metropolitan. The Jetsonesque orb for Merchants S&L. At the foot of Broadway, the six-story First National Bank building, with a neon 1 on the roof. If the temperature was going up, the 1 was filled with ascending red stripes. In a plains town like Fargo, that always gave you hope: warmer tomorrow.

The West Acres Mall was built on the outskirts of town in the early ’70s, and the effect was almost immediate. It was an architectural black hole whose gravity pulled the commercial life of the town to the asphalt wasteland on the far edge of town. They tried everything to keep downtown vital: boutique malls in the abandoned department stores, reconfiguring Broadway to make it car-hostile and pedestrian-friendly, modern plastic awnings over the sidewalks to shield shoppers from the elements. Nothing worked. It never seems to.

But fast-forward to last summer. I was standing on Broadway after sunset, waiting for the freight train to pass. Up and down the street were neon signs for bars, restaurants, coffee shops, stores. Lights shone from the old hotels, now residential or office lofts. Broadway was wide open again, and cars cruised up and down as if auditioning for “American Graffiti.” The magnificent neon-and-bulb marquee for the Fargo Theatre blazed a few blocks away. Downtown was back. How it happened and why is another story; what matters is that it happened, and that Fargo has a collective pride in its restoration and rejuvenation.

It won’t happen everywhere. Most of these main streets are gone for good. Google Street View is useful for reminding us how many main streets slipped into slumber, how many places rich with simple human history are just waiting for someone to bring life back to the brick mausoleums. Waiting for someone to open the old movie theater and splash a story on the empty wall. Waiting for the good times to return—times when the storefronts displayed dresses and appliances, farmers came to town for the Saturday trip, teens flirted at the Woolworth counter, popular songs drifted from a passing car, and all the lights in town came on one by one as the sun descended. It was a good and decent place, and everyone thought it would always be so.

Alas. At least we can tour the remnants of the American Main Street, and pay our respects. Google Street View’s account of these places is a visual eulogy, necessary evidence of the changes wrought on the nation. At some point these empty places will fall, or burn and collapse, but of course the same is true of the stars the Webb telescope sees. There’s always a day when the shopkeeper closes up and clicks off the neon, and the sign never lights again.

But something else turns on for the first time somewhere else, and life goes on.