Cities as Markets

Robin Currie talks with Alain Bertaud about private-sector housing in Bogotá, why tax cuts for specific companies backfire and much more

By Robin Currie

In this interview, Mercatus distinguished visiting scholar Alain Bertaud “talks cities” with Robin Currie. They begin by discussing Bertaud’s recent visit with urban planners in the Colombian capital of Bogotá, his amusement at the planners’ fixation with “magic numbers” and the significance of a croissant. They then move on to consider cities as markets, the future of U.S. cities and more of the ideas in Bertaud’s book, “Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities.”

ROBIN CURRIE: Why were you in Bogotá?

ALAIN BERTAUD: I was invited to take part in discussions with Colombian urban planners. They are trying to deal with a refugee crisis—about two and a half million Venezuelans have moved to Colombia to escape the challenges in their own country. The authorities must integrate these new arrivals, especially in Bogotá, and the city’s urban planners have a key role to play in that process.

CURRIE: How are Bogotá’s urban planners addressing its refugee crisis?

BERTAUD: The authorities have to provide social housing for the refugees. But they know that doing so would mean that the locals must wait longer to be housed themselves and that the result could be resentment against the refugees. So in Colombia, local authorities have decided to rely on the private sector to build most of the housing required by refugees.

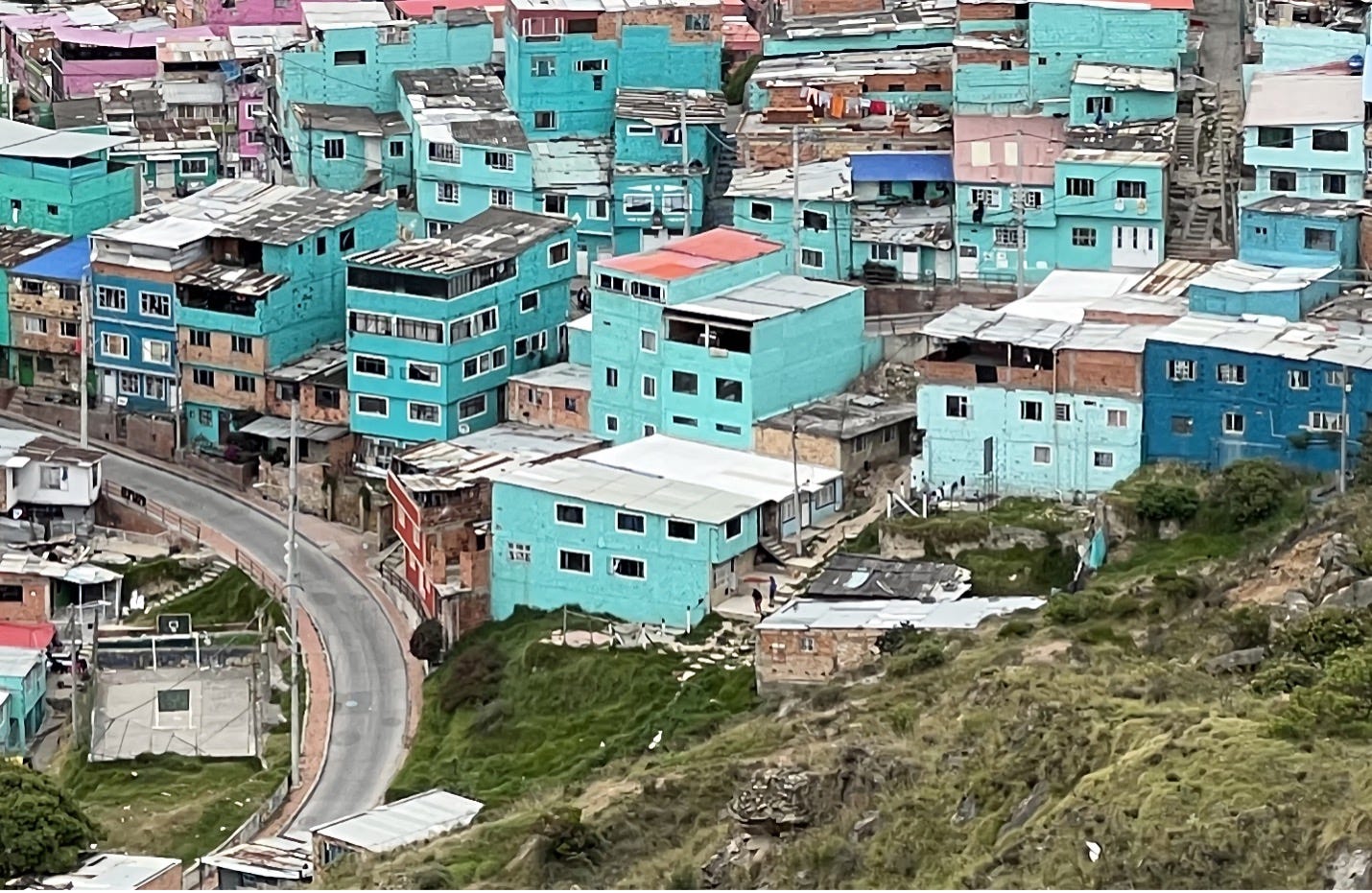

As in most of Latin America, there are many subdivisions in Bogotá that are illegal. The rest of the housing is unaffordable to about half of the population. But they’re not “squatters.” Their subdivisions are illegal because they don’t meet the authorities’ arbitrary standards—standards that do not take into account the income realities of the population.

The authorities have begun to legalize these settlements and will do even more. Yes, some minimum land use regulation and lot sizes still exist in Bogotá, based on what I call “magic numbers.” We joke about those two words: They’re the kind of numbers that urban planners worldwide always use but are arbitrary and hard to rationalize.

Generally, though, in Bogotá there’s an openness to stimulating the private sector as a way to increase the supply of housing—for migrants and for everybody else. Government subsidies are used not to build a limited number of public housing dwelling units, as in the past, but to provide basic infrastructure to new, privately developed settlements using demand-driven norms. This ensures a flow of new affordable housing.

CURRIE: You’ve said cities are primarily labor markets, and that in addition to housing affordability, efficient labor markets need mobility. How does Bogotá fare?

BERTAUD: Bogotá has been extremely innovative in its public transport. It has a bus rapid transit system (the TransMilenio) that is a cheap version of a subway. Buses run in their own lanes and are not slowed by heavy traffic. They also operate between enclosed stations, not just bus stops. That’s where you buy your ticket rather than waiting until you board the bus, which is what slows everything on normal bus lines. As the city expands, the original design of the TransMilenio has to be adapted to the new densities and land use. For instance, a subway is now planned to serve the densest part of the city.

Bogotá is expanding into the surrounding hillsides, which is where the poorest neighborhoods are. There the streets are too steep and narrow for vehicles, and some parts can only be accessed by staircases. So they have developed a system of cable cars for increasing access to the metropolitan job market from the remotest settlements.

The cable cars are usually small and slow, and I was initially skeptical about them. But I rode one of them on my recent visit and changed my mind. The cars take over where the TransMilenio lines end, helping to form a more integrated system and even spurring commerce and development where they meet. I was able to find a good croissant when I got off my cable car in the middle of a recently legalized informal settlement. For me that’s an indicator of growing affluence indeed and integration with the rest of the city!

CURRIE: In Bogotá the authorities are trying to facilitate the development of the city. What happens when governments try to reduce growth in some cities and engineer it in others?

BERTAUD: Take the example of India. In the ’70s, its government embarked on a policy to spur development beyond the big cities. But it was a very expensive undertaking. They invested in infrastructure in parts of the country where there was no demand for it. And that meant starving investment in in Mumbai and Delhi and Chennai, which were growing very fast.

The government also offered subsidies to industries that agreed to move to areas where they did not want to move. That’s never going to work. A company may cash in on the offer and build a warehouse or something like that, but it doesn’t mean the creation of new jobs.

CURRIE: When a city goes into decline, can the decline be reversed?

BERTAUD: In general, the decline is difficult to reverse. When jobs are leaving a city, it’s better for people to move to where the jobs are, not to hold onto the hope that the jobs are going to come back. They’re not.

Think about it: An industry pays taxes to maintain the city. But if a city has to say to companies, “We will pay you to come here,” then it is a city that is already poor because it has lost jobs. It’s a city that will never be well run, one that will always have to pay subsidies to industries that normally should contribute the most to the city’s budget. And companies? A company wants to be close to its customers or employees. But if it selects its location based on a tax rebate, then the company will have to rely forever on it to survive.

A better approach is for the city to improve its transportation system, just as they have done in Bogotá. This would allow companies to increase the size of their labor market by attracting employees from a wider area. But it’s also something that makes the city more attractive for everyone. The same goes for the city’s efforts to address pollution, decrease crime and so on. It benefits all.

Tax cuts for specific companies are the opposite. They come at the expense of everybody else. If the city is going to subsidize Amazon for locating there, then who is going to pay the city’s taxes? The corner barber shop?

CURRIE: Markets vs. design: Would it be correct to say that cites are a mixture of both?

BERTAUD: Despite what people think, nearly all cities are markets.

Now, there are some exceptions, like Brasilia or Canberra or the future capital of Indonesia. These are planned cities. But even Washington, D.C., is a market. Pierre L’Enfant may have laid out the city, and government—the White House, the Capitol—may have been the city’s raison d’être. But he did not say where the lobbyists would be located, where the banks would be. There was none of that kind of zoning. It was just a network of streets. Like other cities, Washington is a city joined by markets.

Cities are a mixture of formal markets and informal markets. And some cities are 50% informal markets. Government interventions can make the lives of the people who live there much more difficult. That’s the reliance on “magic numbers” again—government’s unrealistic norms and its failure to understand the operation of markets.

CURRIE: How optimistic are you about the future of American cities?

BERTAUD: I’m optimistic about the future of American cities because I’m optimistic about the future of America. Americans always bounce back! The enormous intellectual freedom we have here allows us to do that.

Now, there are some bizarre and frightening things happening in cities like San Francisco. They are driven by an extreme ideology and have led to a breakdown in civility and enforcement of laws. But I assume there will be a reaction to all of this, a correction. As someone once said, “Americans can always be trusted to do the right thing, once all other possibilities have been exhausted.” Well, we’re exhausting all other possibilities now.

There’s another quote in my book, from the economist Angus Deaton. He warns that “the need to do something tends to trump the need to understand what needs to be done.” That is always a challenge. Mayors and urban planners should be enablers and facilitators, not the creators and shapers of cities. That’s when cities thrive.