Can Our Government Keep a Secret?

The massive expansion of the intelligence bureaucracy makes preventing leaks impossible

Earlier this month, Airman First Class Jack Teixeira of the Massachusetts National Guard was indicted on six counts of violating the Espionage Act by sharing top-secret intelligence reports. In a quaint throwback to the 1980s, Teixeira allegedly had photographed hard-copy intelligence reports, which he then uploaded to an internet chat room.

The eminent military historian Max Hastings wonders whether this latest embarrassing intelligence leak indicates that the U.S. intelligence community is losing its edge. The leak has prompted articles decrying the culture of unauthorized leaking and urging more compartmentalization of information, better background checks, a reduction in the number of security clearances and measures to limit the sheer amount of classified information.

Although the White House has downplayed the seriousness of the Teixeira leak, the media has been reluctant to publish the compromised intelligence reports themselves. This is probably because the documents offer some insight into how the Pentagon thinks the war in Ukraine is going (the short answer: Ukraine is far from winning), and the media has been loath to report criticism of the conflict. In any event, the press arbitrates what classified government documents the public gets to see.

In response to the leak, Senators Mark Warner (D-Va.) and John Cornyn (R-Texas) are sponsoring bipartisan bills to cut back on the amount of intelligence that is considered sensitive and therefore must be protected, a problem termed “overclassification.” Their initiative is sensible, but it is unlikely to achieve its goals. The expansion of the intelligence bureaucracy by definition means more classified information and more security-clearance-holding employees. Moreover, secrecy is the nature of bureaucracy. Security procedures can always be tightened, but the bloated bureaucracy renders overclassification and leaking inevitable.

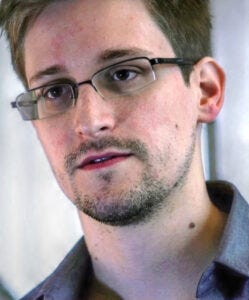

The Snowden Snow Job

Teixeira’s case bears some interesting similarities to that of Edward Snowden, who infamously—or heroically, as some still would have it—disseminated classified information 10 years ago this month. Both Teixeira and Snowden worked as IT technicians, which gave them top-secret clearances and access to sensitive material (or knowledge about how to get such access).

Snowden’s leak has been the most consequential since Daniel Ellsberg’s 1971 theft and delivery of the classified Pentagon Papers to The New York Times and The Washington Post. Ellsberg described leaking these papers, which exposed government decision-making on the Vietnam War, as “a patriotic and constructive act.”

In 2013, Edward Snowden ostensibly had a similar motivation. As a newly hired contractor for Booz Allen Hamilton, Snowden started stealing National Security Agency (NSA) secrets concerning its bulk metadata acquisition methods and many other programs. Although officially he had limited access, Snowden used deception to obtain passwords to 24 compartmented databases, and he then downloaded 1.7 million documents to thumb drives. It is still unclear how he gained this access.

Before the NSA became aware of the theft, Snowden fled to Hong Kong. There he shared with media contacts documents on the NSA’s collection of U.S. citizens’ telephone and internet metadata and on other classified programs that allegedly violated Americans’ civil liberties.

Carrying many more sensitive documents, Snowden next flew to Russia, taking advantage of a very slow response by U.S. law enforcement. An employee from Julian Assange’s WikiLeaks helped Snowden with the travel arrangements and accompanied him on the trip. Putin permitted Snowden to enter Russia on an expired U.S. passport and without a visa.

Snowden was quickly lionized by the media and by Hollywood as a defender of civil liberties, even though his real objective was probably to level the intelligence playing field for United States’ great power rivals.

Snowden in Hindsight

In “How America Lost Its Secrets,” journalist Edward Jay Epstein explains that Snowden followed a radical ideology according to which all information should be completely accessible. Snowden also deceived his media contacts about the nature of his illicit haul, showing them only classified documents concerning domestic surveillance and concealing how most of his haul involved data on foreign governments and programs targeting terrorist groups. To undermine secrecy, Snowden used secrecy.

As for Snowden’s impact, Epstein speculates that China and Russia used the information he brought them to take the offensive against America’s sensitive computer systems. Some significant breaches of federal systems occurred shortly afterward, including the huge hack of the Office of Personnel Management in 2014.

Snowden might not get the same positive reception in the media now that he got in 2013. The media now seems more receptive to government intrusion and probably would be less forgiving of his Russia connection. Moreover, the debate over collecting Americans’ metadata didn’t advance very far after Snowden’s revelations. Ten years later, the government still enjoys easy access to metadata collection.

Although Snowden arguably committed treason, even some of his harshest detractors admit that the leaks concerning U.S. bulk data collection programs prompted a necessary debate. Barton Gellman, who revealed Snowden’s leaks in The Washington Post, has denied that Snowden’s actions significantly damaged national security. He believes they did more good than harm.

A Deluge of Secrecy

In “Necessary Secrets,” Gabriel Schoenfeld demonstrates that the media has a long history of oscillating between supporting government efforts to protect classified information and trying to expose government secrets. We might be seeing a period when the pendulum has swung back toward more cooperation between media and the government. Perhaps the mainstream media’s reluctance to publish recently leaked documents signals greater cooperation with government to protect classified information. This would signal a rule shift since the time of the Pentagon Papers leak, when anything verified was fair game.

The U.S. has always experienced a strong tension between secrecy and publicity, as Edward Shils pointed out in his classic book “The Torment of Secrecy.” But the tide turned significantly toward secrecy during World War II, especially with the development of the atomic bomb. That is when the government’s secrecy complex began in earnest.

In his book “Bomb Power,” historian Garry Wills identifies the development of the bomb as the true beginning of the era of secrecy. Protecting information was always a major problem for those involved in General Leslie Groves’ Manhattan Project. Ironically, in the interests of protecting information, the project excelled at keeping its scientists from knowing what each other were doing. But it failed completely to keep the Soviets from knowing what the whole project was doing.

After World War II and the Cold War came 9/11 and an even greater expansion of the intelligence bureaucracy. Two new major institutions—the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence—added to the classified information deluge. In “Top Secret America,” Dana Priest and William Arkin demonstrate how, following the vast expansion of the intelligence community after 9/11, senior executives couldn’t keep track of all the secret programs under their own purview.

In 2010, the Obama administration passed legislation to reduce overclassification. It had no discernible effect.

The Underlying Problem

But the bureaucracy, not the policy decision to overclassify, is itself the issue. The late U.S. Senator Daniel P. Moynihan noted in “Secrecy: The American Experience” that the very nature of bureaucracy requires a jealous guarding of information. Secrecy, he claimed, is simply regulation. Intelligence agencies regulate access to information, and this information is their main product. The government is not going to give up or lessen this basic authority.

Secrecy is necessary when national security is obviously at stake, but sometimes the lack of transparency leads to grave policy mistakes and covers up abuses of power. As Moynihan stressed, excessive secrecy has contributed to some of the worst political controversies in recent U.S. history, such as Watergate, the Iran-Contra Affair and—more recently—Russiagate.

In the balance, Moynihan believed the secrecy regime was not worth the cost of U.S. democracy. He declared that, ultimately, “secrecy is for losers.”

Living With Leaks

The “culture of openness” Moynihan hoped might emerge after the Cold War never arrived. For example, since 9/11, the intelligence bureaucracy has developed considerable redundancy regarding counterterrorism, despite a greatly diminished threat.

Attempts to make the government more transparent will require significant institutional pruning. But, as Gellman points out in his thoughtful book “Dark Mirror,” Congress and the American people hold the intelligence community to an impossible standard: It must know everything. That gives the bureaucracy no incentive to cut back on secret information and classified programs.

In fact, most calls for intelligence reform these days seek to expand bureaucracy, not contract it. For instance, new proposals to add an intelligence agency to the Commerce department or to create an open-source intelligence agency would probably be steps in the wrong direction.

No doubt the intelligence community will tighten up on security in response to the recent Teixeira fiasco. More ambitious plans to limit classified information will likely fail, notwithstanding the good intentions of their proponents. Absent a major overhaul, perhaps the only solution is to treat these classified leaks as “leakage,” the way Walmart treats minor shoplifting—as an acceptable cost of doing business, if kept to manageable levels. After all, even dramatic and seemingly damaging leaks like Snowden’s may be less costly in the long run than further increasing the intelligence bureaucracy.