Book Review: The Fight for Free Speech Is a Battle That’s Never Over

An ambitious survey from antiquity to today shows how the lessons of the past can help us confront the growing threats to freedom of expression now

By Allen Mendenhall

Free speech is constantly under threat. The headlines about book-banning, censorship on social media and silencing speakers on college campuses seem endless. Each side of the partisan divide accuses the other of working to outlaw their opinions, or worse. But charges that speech is being suppressed are still taken seriously, suggesting there continues to be widespread, nonpartisan support for the ideal of free speech.

Perhaps we shouldn’t have these simplistic “sides.” Perhaps a society that values free speech should make pluralism and mutual respect its priority over uniformity and exclusion. Perhaps intelligent debate and constructive disagreement are indispensable to democracy.

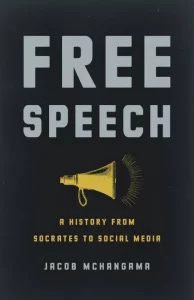

The issue of free speech is at the top of the news this week with Twitter’s board agreeing to sell the company to Elon Musk. Many conservatives and libertarians see the deal as a victory for free speech while many progressives fear the social-media site will be flooded by misinformation that should be restricted. But “‘free’ speech is never ultimately won or lost,” cautions Jacob Mchangama in “Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media,” an ambitious, sweeping survey of free speech (and its denial) from antiquity to today. He’s well-equipped to take us on this journey—a lawyer and human-rights advocate, he’s the founder and executive director of the Danish think tank Justitia and the host of the podcast, “Clear and Present Danger: A History of Free Speech.”

A key takeaway from the book is that our moment, however uniquely tumultuous it seems, isn’t so different from past eras. What’s more, examples from history are excellent guides through today’s political controversies because we can be more objective about the past than we can be about the issues we’re immersed in today.

New technologies bring both opportunities and problems. Just as Facebook and Twitter revolutionized communication for good and bad, Gutenberg’s printing presses “eased communication and the dissemination of learning” while churning “out a steady stream of virulent political and religious propaganda, hate speech, obscene cartoons and treatises on witchcraft and alchemy,” notes the author. The internet has facilitated a robust marketplace of ideas unmediated by government regulators such as the Federal Communications Commission. But it has also spread extremist ideology, disinformation and misinformation, and allowed marketing and advertising that harm mental health and well-being. Creating forums where speech flourishes without unnecessary constraints, where people converse in good faith to improve clarity and understanding, has never been easy.

Banning Ideas Doesn't Work

Efforts to police speech, moreover, have unintended effects. The great paradox is that ideas gain momentum when the authorities attempt to ban or suppress them. Mchangama makes this point with Martin Luther, the catalyst of the Protestant Reformation whose teachings on indulgences, grace, sacraments, worship and scripture created a torrent of religious populism that far exceeded his expectations. The more the Catholic Church and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V tried to clamp down on Luther, the more attention they drew to Luther’s grievances.

There was a time when espousing the Copernican view of the sun could get you convicted of heresy (consider the case of Galileo, who spent the rest of his life under house arrest after his conviction). Yet the history of free speech isn’t only about repression, crack downs and draconian restrictions. Mchangama offers up the decentralized, cosmopolitan Dutch Republic as a model of pragmatic accommodation with an “egalitarian public sphere.” He says, “Between 1600 and 1800 no one read or printed more than the Dutch. An estimated 259 books and pamphlets were consumed per 1,000 inhabitants annually during the second half of the 17th century.” Thanks to a “weak political center,” “local autonomy” and strong “provincial institutions,” the Dutch cultivated a “space for heterodox ideas and daring publications to flourish.” Because it embraced commerce and trade, the Dutch Republic was open to foreign influences and received and transmitted knowledge across seas and borders.

Who's the Heretic Today?

What is the equivalent of a “heretic” or a “blasphemer” in our secular age? Is it the protesting Canadian trucker or the Parisian demonstrator decrying coronavirus regulations? Or is it an activist denouncing Trump and Trumpism? Is the dissident the one who questions whether transgenderism is scientifically sound, or the one who teaches about nonbinary gender fluidity in the face of social opposition? This may mean that it’s hard to know which dogma most people subscribe to, or that we have competing dogmas as public opinion fractures. Thus, we must be alive to the possibility that even our firmest commitments contain error.

The events, figures and disputes populating this book are many and diverse. Socrates, Aristotle, Pericles, Spinoza, Muhammad, William Laud, Kant, Locke, Milton, John Stuart Mill, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, William Penn, Napoleon, Otto von Bismarck and Solzhenitsyn all figure prominently. Mchangama scans antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Reformation, the Enlightenment, the American founding, 19th century Europe and more to show that free speech cycles through periods of flourishing and retreat, that it never enjoys permanent growth.

The author won’t provoke fury with his telling of Henry VIII’s attempts to stamp out William Tyndale’s vernacular English translation of the New Testament, or of distinctions between Karl Popper’s and George Orwell’s takes on freedom of expression. Citing instances from recent politics, however, might divide readers, who, of course, retreat to their partisan camps to mount predictable, programmatic defenses. That’s why historical sketches are effective: They are so remote from our crises and contexts that we’re less tempted to choose teams; we can evaluate the evidence as disinterested observers unconcerned that we’ll offend anyone.

From George Floyd to Alex Jones

Yet Mchangama doesn’t shy away from today’s conflicts. His concluding chapters address George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, the treatment of LGBTQ communities, European hate speech laws, Big Tech, the attack on Charlie Hebdo’s offices, the Chinese Communist Party, blasphemy laws in Islamic countries, Alex Jones, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and the Arab Spring. They lend urgency to his plea that it “is up to each of us to defend a culture tolerant of heretical ideas, use our system of ‘open vigilance’ to limit the reach of disinformation, agree to disagree without resorting to harassment or hate, and treat free speech as a principle to be upheld universally rather than a prop to be selectively invoked for narrow tribalist point scoring.”

Even ardent advocates of free speech acknowledge its limitations: People cannot, without legal consequences, slander an innocent’s reputation or perjure themselves in court. Victims of threats or harassment, moreover, have recourse to the legal system. Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was known as a champion of free speech because of his dissenting opinion in Abrams v. United States in 1919 and other opinions. But he famously stated in Schenck v. United States, also in 1919, that the “most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” Lines must be drawn somewhere.

Surviving the Test of Time

Where to draw them is the perennial puzzle. Mchangama would have us err on the side of openness and tolerance. His dizzying if exhilarating march through the centuries is impressive in its breadth, and it displays enough depth to satisfy scholarly and popular audiences alike. This wide range validates his claim that “while free speech may often seem like an abstract and theoretical principle when confronted with concrete and tangible threats and harms, it is a principle based on millennia of practical and often bloody experience with the consequences of its denial and suppression.”

In an intolerant culture that persecutes heterodox beliefs, compels recantations and stifles contrary interpretations of verifiable facts, self-censorship is the outcome, the extent of its pervasiveness unknowable. Mchangama avers that “there is no way of knowing how many authors may have self-censored” to avoid their listing in the papal Index of Prohibited Books (first promulgated in 1559 and abandoned, finally, in 1966). His statement applies beyond that one catalogue of names and texts. How many college students fearing the judgment and wrath of their peers and professors, conceal their political opinions? He cites a Cato Institute study finding that “62% of Americans self-censor their political views for fear of offending others, with only those who identify as strongly liberal confident of speaking their mind freely.”

We need places where reasonable people can debate civilly and disagree productively, recognizing their shared humanity and contributing to the exchange of ideas. Social media and legacy journalism have yielded those places to the loudest and angriest voices, and universities are failing to entertain rival viewpoints. Disagreement is inevitable in a diverse, multicultural society; if the discourse deteriorates, society may succumb to coercion and violence as opposing camps vie for supremacy.

The Realities of Progress

“Perhaps the most striking feature of the free speech recession,” says Mchangama, referring to the setbacks for free speech around the world over the past generation, “was that its onset and acceleration coincided with the triumph of the most revolutionary breakthrough in communications technology since the printing press.” Progress is messy as humans adjust to technological and cultural changes that upend norms and challenge presuppositions. Advances in science, medicine and the arts have proceeded through fits and starts, mistakes and repairs, practices and theories. The bottom-up proliferation of culture and information is always a threat to “the establishment.” But in this era, infractions against norms are no longer chiefly religious except, perhaps, under Islamic regimes.

When Alexis de Tocqueville observed the vigorous character of debate in America during the 19th century, ideas circulated in public squares, civics organizations, clubs, mutual aid societies and schools. You could add to these groups in our day parent-teacher associations, youth sports, tailgate parties and more. But the internet has changed our interaction. Anonymity in multiverses and metaverses has led to vilification, mob psychology, alienation, depersonalization and dehumanization as trolls shriek and squeal, bully and harass, pursuing power and attention rather than insight or agreement. Nameless, faceless avatars appeal online to raw emotion over disciplined reason. Will free speech succeed in this virtual world of simulation, where individuals cannot sit side-by-side, face-to-face?

It must, for everyone’s sake. The world isn’t a game. It’s real. And the consequences of denying free speech are, too.