Book Review: China’s Threat to Openness

The authors of a new book, An Open World, offer a strategy for preserving the American-led order and the openness that underpins it

These days the word “openness” is not always used in a positive context. The word can conjure up notions of unfair trade, the loss of American jobs to other countries such as China, and exposure to foreign health and security risks. But if we step outside that rubric and look at even recent history, we can trace the freedoms, security and prosperity that we all enjoy today straight back to the openness that this country has fought to maintain across the globe since at least World War II.

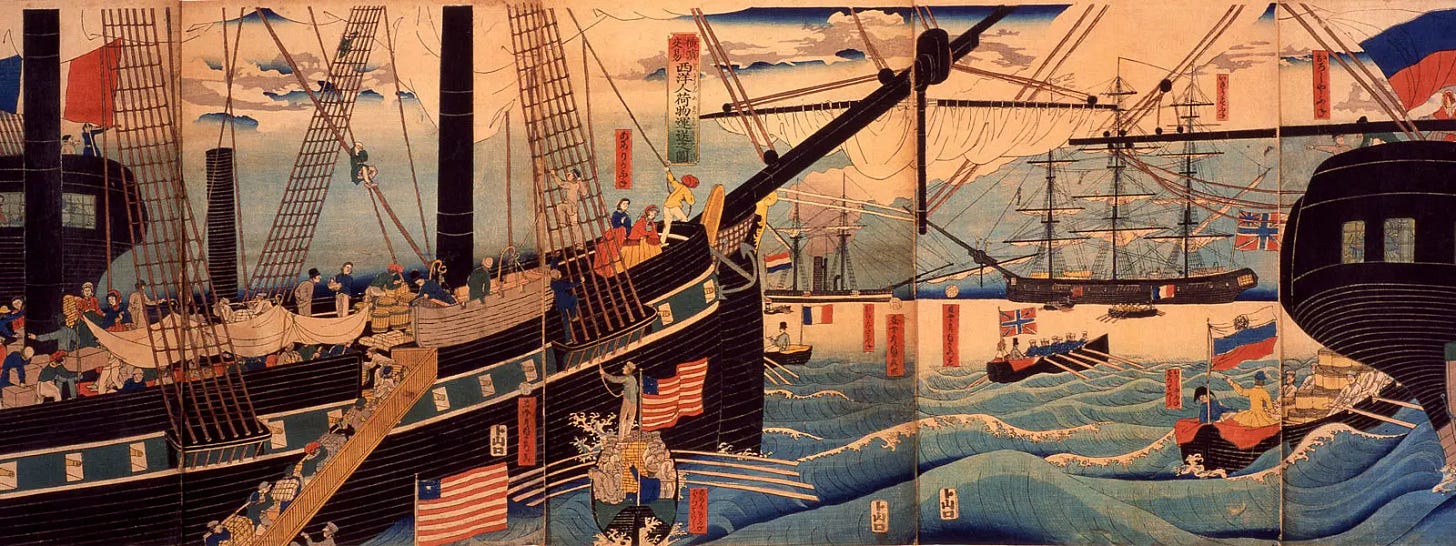

That openness was part of the grand vision and governance that came out of a postwar consensus, including the discussions at Bretton Woods—a popular New Hampshire ski resort today but the site of a conference of 44 allied nations in the summer of 1944. The citizens of these countries and their leaders from around the world were still in the midst of the Second World War. But the end of the conflict was in sight, and the participants were keen to rebuild the world in such a way that another war like it would not occur. Cross-border openness to commerce and information and the interdependence that resulted from that openness were seen as ways to help keep the peace.

Fast-forward to today, 75 years later, and we face a rising power in China that is on track to become the largest economy in the world. Indeed, by some measures, it already is the largest.

Owing to its sheer size, China will change the world. The question for America, as posed by authors Rebecca Lissner and Mira Rapp-Hooper, is whether China’s emergence will happen in a way that enhances or threatens our cherished way of life. In their new book, An Open World: How America Can Win the Contest for Twenty-First-Century Order (Yale University Press, 2020), they lay out a strategy aimed at ensuring that China’s rise doesn’t have a negative impact on the U.S. or the global order it built.

To be sure, U.S. security and prosperity can coexist with that of China. Increasingly, however, China’s efforts to become the world’s dominant power threaten that security and prosperity. Ely Ratner, deputy national security adviser to then-Vice President Biden, has stated, “On most issues of consequence, there is simply no overlap between Xi’s vision for China’s rise and what the United States considers an acceptable future for Asia and the world beyond.”

Lissner and Rapp-Hooper point out that China’s actions increasingly reveal an authoritarian regime that does not value, share or respect openness and the freedoms the United States and our allies hold dear. They argue that the U.S. must oppose such moves toward closure, and they lay out a grand strategy for doing so.

The authors bring academic and applied policy rigor to their work, with Lissner an assistant professor in the Strategic and Operational Research Department at the U.S. Naval War College and Rapp-Hooper a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and currently on leave to provide advice to President-elect Biden’s team as he prepares to take charge.

Opposing Chinese Ambitions

According to the authors, there are two types of Chinese ambitions the U.S. should oppose. One is a kind of economic dominance that works to rob a country of its political independence and ability to make free decisions domestically and internationally in international institutions. Often cited is how China leverages loans and assistance to developing nations in Africa, the Pacific and elsewhere to garner votes against Western-backed candidates and proposals at the United Nations.

Another ambition that needs to be fought is China’s efforts to leverage technology and subjugate the free flow of information to state decision-making, resulting in a closed internet. This sort of dominance also allows China to persuade other countries to enact a similarly closed model.

In Nikki Haley’s account of her time as the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, she notes, “China’s leaders manage the threat to their rule by creating an Orwellian surveillance state: Xi has concentrated unprecedented power in his own hands, using facial recognition and big-data technologies to monitor huge masses of people. For the same reason, his government now strives for world leadership in 5G networking and artificial intelligence.” This, the authors argue, is why we cannot afford to let China control the internet outside of China.

A Way Forward

As the authors make clear, there are a number of effective ways for the United States to oppose these intentions. For instance, they call on the government to increase research and development spending. Specifically, Lissner and Rapp-Hooper argue that the U.S. is underutilizing its existing economic and technological advantages, and they lament the decline in R&D spending over time. (Data from the American Association for the Advancement of Science show that government spending on research and development as a share of GDP did decline after the Cold War, although the trend seems to be driven by a decline in spending on development or applications while the share of basic research spending has stayed constant.)

As a result of this overall spending decline, U.S. tech companies have had to look elsewhere for profits, the authors say, and in so doing, they have become untethered from U.S. national interests. Meanwhile, the Chinese Communist Party has fostered a close relationship between the private sector and the centralized government and has used those connections to reform and solidify digital authoritarian control.

A second way to oppose China’s ambitions, they argue, is to lower the barriers to attracting talent and bridge gaps between the government and the private sector. The Department of Defense (DOD) is a good place to start, including a reform of DOD’s procurement and acquisition processes (i.e., make it easier for DOD to buy software, as summed up nicely during a recent discussion of the book with the authors). Other ways to build talent and bridge gaps include streamlining the process through which DOD can work with agile startups, instead of just massive industrial giants, and creating more fellowships to build ties between tech talent and DOD, perhaps even including something like a tech reserve corps.

Third, the authors argue that the federal government should take a more prominent role in the direction of key technologies such as 5G, artificial intelligence and quantum computing. For instance, the government’s role is clear in forging an alliance with democratic nations in an effort to alleviate reliance on China and mitigate the corresponding espionage and cybersecurity risks.

Some of these proposals left me questioning how such calls to action might evolve in the policy space, given the poor track record of the government in picking winners and losers. But there is a fine line between choosing winners and losers and facilitating the provision of particular services. Public-private partnerships offer intriguing ways around such traditional drawbacks. There is ample evidence that public-private partnerships can act as an efficient mechanism for the provision of services, at least in infrastructure.

The authors call for new uses of these partnerships and highlight a distinct “American model of public-private partnership that protects the innovation and investment catalyzed by market forces while also directing corporate dynamism toward shared national objectives.” This will be an interesting policy space to watch in the Biden administration.

In a recent podcast discussion to promote the book, Lissner and Rapp-Hooper note that spending is not the only important aspect of their grand strategy. Another large piece of their plan involves reframing the stakes with U.S. policymakers at all levels of government and the private sector. Reframing the stakes with our global allies already appears to be underway as discussions progress on the need for international institutional reform (e.g., the World Trade Organization) and on building alliances to address technological issues (e.g., a pooled 5G network, coordinated AI R&D spending, and cooperative arrangements in data sharing and export controls).

The authors also underscore the importance of the U.S. getting its domestic house in order. News and information illiteracy, domestic government dysfunction, political polarization, democratic decay—we ignore these issues at our peril. It’s not just about how big our economy or our military is. If our domestic house is a mess, we will not be able to leverage these other strengths as effectively.

The Day After

An Open World will not be the last book to offer a grand strategy, but it is one of the first to be written by a new generation of strategic thinkers. It’s fresh. It’s smart. It’s not concerned with defending policies of the past or any particular ideology. The authors are free agents, and they set out an unapologetic strategy for openness in a time when many Americans seem to be willing to withdraw from our global role.

For those who think everything will go back to “normal” the day after President Trump leaves the White House, think again. These geopolitical challenges were brewing long before Trump arrived and will only grow in importance in the coming years.

An Open World is a real treat. It is a call to action for “the day after.” Those who serve the coming administrations should read this book and use its insights to take effective action against the growing threats to our open world.