Blaming the Gipper

Showtime documentary on Reagan assigns too much blame to the former president’s economic policies for today’s income inequality

By Tim W. Ferguson

Political progressives have an opening to rewrite recent U.S. history, and they don’t intend to stop with the Trump years. The deepest left has already gone way back (as far as the celebrated 1619 Project), but for most social welfare Democrats, it’s enough to erase the stain of Ronald Reagan. That effort is very much at work with attempts to link today’s spiking income and wealth inequality with the tax rate cuts and public benefit restraints of the 1980s.

You can find those references in much contemporary punditry. But the connection also receives an entertainment gloss in the Showtime network’s recent four-part documentary, “The Reagans.” Helmed by Matt Tyrnauer, a Vanity Fair-cum-Hollywood storyteller, the slick production assembles valuable footage of Ron and Nancy’s public lives to renew familiar notions of the 40th president being a confected American hero, a fantasy creation even in his own mind. The film does include painful instances of fabulism, which all but the most diehard Reaganite would acknowledge about his career, and Ron Reagan Jr. and Kitty Kelley predictably annotate the action. The dozen presumed allies of the presidential couple who are given airtime by Tyrnauer offer only a weak rebuttal.

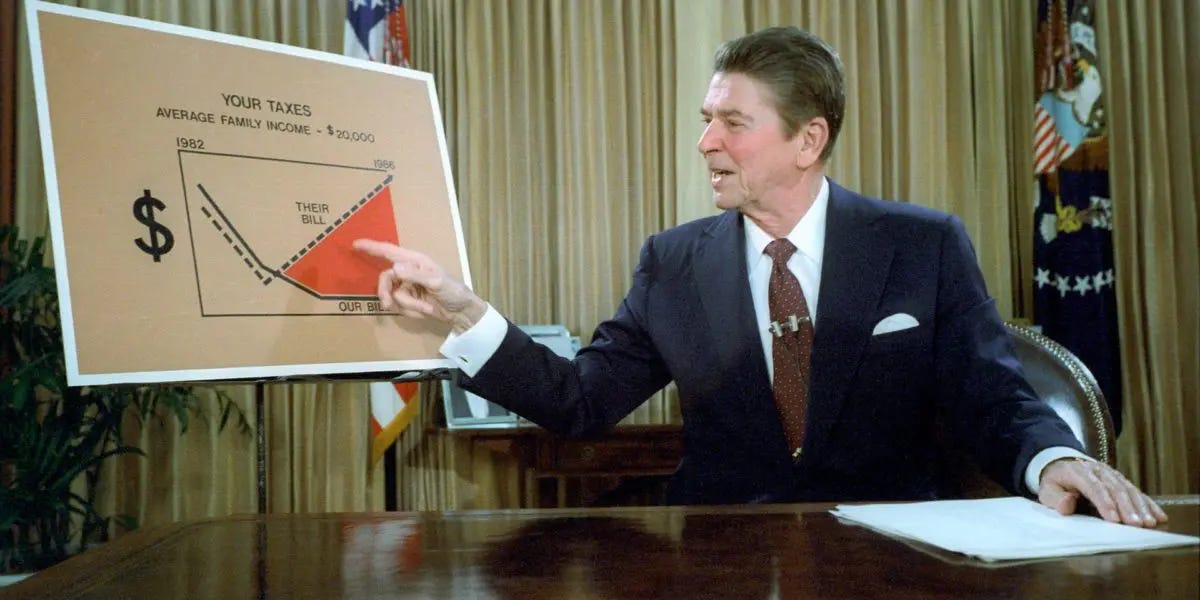

But what I was stuck on was the documentary’s economic indictment of Reagan, most fully developed in Part 3, “The Great Undoing.” It picks up with Reagan’s first term in the White House, through a bitter economic downturn, and on to 1984’s “Morning in America” ads capitalizing on an uptick in spirits. Through it all, what was being undone, we are told, were the foundations of the middle class, ostensibly laid since Franklin D. Roosevelt.

As Tyrnauer, in an interview with left-leaning journalist Robert Scheer (who also figures prominently in the documentary), put it: “Reagan [was] able to be a sort of charming master of ceremonies with really dangerous beliefs in a really wicked economic program that undermined the social contract of the New Deal in this country and caused a great deal of damage.”

Ironically, when it comes to economic policy, the program does not draw much on the discipline itself. Jonathan Alter, a longtime left-liberal journalist, was a consulting producer and provides the commentary backbone. Supporting the theme of Reagan’s rich-white reign of error are a few professors and MSNBC talking heads with questionable bona fides on pre-millennial matters. Apart from the top economic adviser to Barack Obama, Jason Furman, who had three quick sound bites, the closest thing to an economist is Derek Shearer, who came out of the Tom Hayden camp in 1970s Santa Monica to go on to a role in Bill Clinton’s Commerce Department.

Of course, there are credentialed economists who, had they been retained, would gladly have joined in this critique of Reaganism as a roadmap for what culminated in Trumpian dystopia. Paul Krugman has been writing that column since the 1980s, it seems. (Truth be told, he’s only been at it since 2000, in The New York Times. Krugman actually worked under Martin Feldstein at Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers.) In fact, if Krugman or another literate economist had been called on to cite some figures, the production might have had more of a leg to stand on.

Instead, there’s an hourlong circumstantial case, building to the damning final title sentences: “In the years since the Reagan tax cuts, the United States has seen the largest redistribution of wealth since the Gilded Age. The richest 1% today have more combined wealth than 90% of all Americans.”

Statistics on rising wealth and income inequality show a distinct correlation with financial booms. As we know, these can occur during control by either party, although usually they are traceable to policies that preceded them. But for purposes of Tyrnauer’s indictment of Ronald Reagan, it is useful to ignore the latter years of Jimmy Carter’s presidency, when an upward spike for upper incomes began. This probably resulted both from a recovery (later inflationary) from the mid-1970s recession and from cuts in capital gains taxes that some Democrats in the congressional majority made possible.

In any case, the Reagan takeoff for the rich did occur, but not, as the documentary suggests, as an immediate result of Reagan’s 1981 fiscal legislation. The bull market didn’t begin until August 1982. Surely, the further capital gains break of the previous year played a part, but Reagan’s biggest top bracket rate cuts came in the (again, bipartisan) 1986 reform bill, which none of Tyrnauer’s experts mentions. Very few pop histories of the 1980s do because it doesn’t fit neatly into familiar grooves. After all, it was an assorted swipe at vested interests that even curtailed the “three-martini lunch” deduction, which we just got back under Donald Trump.

Incomes, and how they are taxed, figure significantly in wealth disparities, but asset prices can matter more. When stock and/or bond markets rise, their holders reap equivalent gains, at least on paper. The same goes with owner-occupied housing, which is not always in sync with other assets and can also be affected by local factors. (Consider the modest homeowner in Palo Alto, California, in the 1970s—easily a millionaire a few decades later, and Ronald Reagan had little to do with that.) In this documentary, Reaganism is depicted as particularly hurtful for minorities, but the biggest dent to the fortunes of affluent Blacks (those in the 75th percentile) in the last 30 years was the 2007-08 crisis tied to subprime mortgages.

Similarly, the Federal Reserve is a nonpartisan force whose tightening or loosening responds more to the temperature of the economy than to ideology. If you don’t have assets, or you put your savings into interest-bearing accounts that no longer pay much, you will be left behind during periods like, well, the pandemic of 2020. When the annual charts get updated soon, we will surely see another spike in inequality. Is this really Reagan’s legacy, as the documentary suggests?

Matching the tax policy disaster of 1981, in Tyrnauer’s lens, was Office of Management and Budget Director David Stockman’s slashing of relief payments and support services, framed (as the Reagans and their plutocrat friends partied away) in the context of rising unemployment through 1982. One thing had little to do with the other. There’s no question that real cuts occurred for recipients of various programs aimed at the poor and near-poor, even if Stockman’s main targets were the agencies and arms for delivering the assistance. (Remember CETA?) But the factory-gutting recession of 1981-82, following the Paul Volcker Fed’s crackdown on inflation, was the real body blow to the middle class.

Similarly, the symbolic significance of Reagan’s firing of striking air traffic controllers in 1981 is assigned blame by Tyrnauer & Co. for the decline of collective bargaining generally, but private-sector unionization rates had already begun their steep fall by the late Carter years. Appointees at the National Labor Relations Board did matter—a point a bit too much in the weeds for a Hollywood film to cite. But even there a close 1985 reading found Reagan’s influence within the norms of Republican presidents.

Reagan also gets blamed for worsening poverty. And indeed, the U.S. poverty rate did spike during his first term in office—although the increase began during the 1980 (pre-Reagan) mini-recession. Beginning in 1985, however, the poverty rate turned down, dropping for the rest of the Reagan presidency as the economy boomed.

Nuance is not what Showtime brings to social science. There are indeed economic consequences from policy choices, even if they may defy broad generalization. If the supply-side or pro-market agenda doesn’t bring universal prosperity, then close analysis might point to how an opposition, if favored by an electoral majority, could raise more boats. Yet a storyline that traces myriad unwelcome outcomes back to a simple, poisoned source is unlikely to be any more true than a gauzy political commercial that told America that Ronald Reagan had put everything right.

Unfortunately, as Showtime demonstrates, we have entered an intellectual climate that is quick to render verdicts of history that will stigmatize and sweep away what were, and are, valid political challenges to America’s FDR middle-class folklore. But all confections deserve a finer ingredients review.