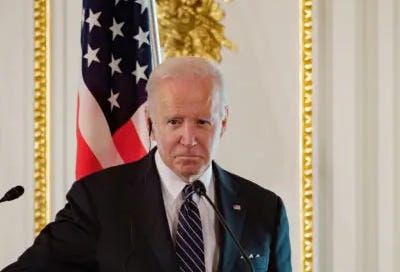

Biden’s Explicit Promise To Defend Taiwan Is Bad Policy

Strategic ambiguity and tactical certainty is what will deter Chinese aggression

By Walter Lohman

During his visit to Japan, when asked whether the U.S. would defend Taiwan militarily, President Joe Biden responded, “Yes, that’s the commitment we made.” He said a very similar thing involving this “commitment” during a CNN town hall last October.

The president is mistaken in two ways. One, the U.S. has no such “commitment.” And two, making such a promise is unnecessary and unwise.

A Commitment To Act?

The U.S. once had an explicit obligation to come to Taiwan’s defense in the event of a conflict with China. It was enshrined in a bilateral mutual defense treaty ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1955. There the U.S. and the Republic of China (Taiwan) agreed that they would “act to meet the common danger” represented by an attack on the territories of either county. This same language also appears in Article V of the U.S.-Japan and U.S.-Korea security treaties.

However, in normalizing relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1979 and dropping diplomatic recognition of Taiwan, President Jimmy Carter abrogated the mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. What the U.S. ended up with instead are the relevant security provisions of the Taiwan Relations Act. When Carter sent draft legislation to the Hill for what would become the TRA, his principal objective was to establish the basis for continuing an unofficial relationship with Taiwan. Congress had bigger plans: While it wanted to establish unofficial relations, it also wanted to reconstitute the mutual defense treaty as best it could under the circumstances.

In the TRA, the mutual defense treaty’s security guarantee became a legal commitment to “consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means . . . of grave concern to the United States.” There is no reference to “act[ing] to meet the common danger.” In its place, the TRA directs the president to “inform the Congress promptly of any threat” to Taiwan and to work with the legislature to “determine . . . appropriate action by the U.S. in response to any such danger.”

So, President Biden cannot be referring to a commitment made in the mutual defense treaty, which is now defunct, or in the TRA, which makes no promise to act. Thus, experts on the topic have assumed his assurances were gaffes. What has kept the peace since 1980 is the unstated prospect that the U.S. will defend Taiwan, the oft-referenced “strategic ambiguity.”

Strategic Ambiguity, Tactical Clarity

Ambiguity keeps the peace by keeping U.S. options open and keeping the Chinese guessing. Since the mutual defense treaty was abrogated, Taiwan has developed into a democracy. It has its own politics and a determined faction in favor of formal, expressed independence. For all practical purposes, Taiwan is already independent, as President Tsai Ing-wen likes to point out. Those in Taiwan lacking her subtlety and skill—and frankly, sense of responsibility—want to push the envelope. But a declaration of formal independence is for China (which would rather erase Taiwan’s existence altogether) a no-kidding casus belli. As such, a clear U.S. security guarantee for Taiwan puts the trigger for the use of American forces in the hands of Taiwanese politicians.

In the event of some sort of declaration of independence—something Taiwan flirted with seriously in the early 2000s—the U.S. will be left with two choices. It can go to war to back up its threats at a time and place chosen by some other capital. Or it can tell Taipei, “Sorry, you’re on your own. Didn’t mean to lead you on”—a breach of faith that would do calamitous damage to the range of global U.S. security interests.

By contrast, ambiguity means the Chinese must plan for the eventuality of the U.S. using force. And it certainly is. Everything about Chinese military planning, from doctrine to procurement, is centered around possible conflict with the U.S. over Taiwan. The objective of American policy is to sow enough doubt in the minds of Beijing decision makers that they never feel sufficiently prepared for a showdown with the U.S. Washington does this best not by rhetoric, but by demonstrating it has the capability to defeat China if it ever does go to war with it over Taiwan.

One could call this “tactical clarity.” With tactical clarity, strategic clarity is superfluous. Without tactical clarity, all the assurances in the world are meaningless. And the combination of strategic clarity with the U.S. military’s weakening capability to keep its promises is recklessly provocative.

The greatest irony of the current brouhaha over President Biden’s personal security guarantee to Taiwan is his apparent failure to grasp all of this. He actively participated in the Senate debate over the TRA in 1979 and supported it. He clearly understood the tradeoffs Congress made to maintain peace and security in the region. By contrast, President Donald Trump, with no prior experience in foreign affairs and not known for precision in his rhetoric, got the policy exactly right.

In August 2020, when asked about what he would do if China made a move on Taiwan, Trump said, “China knows what I’m gonna do. China knows. . . . I don’t want to say I am gonna do this or I am not gonna do this.” This is strategic ambiguity in a nutshell. President Biden would do well to follow the advice of his staff and get back to it.