Aspicable Me

I may have helped perpetuate a lie about our culture as told by ‘regrettable food,’ but I don’t really regret it

The other day, a box arrived at work. It was full of recipe books from the 1970s. Brown chunks in orange pots. I’ve never met this person on the return address label—why would they send me this?

Because there was a knock on the door in 1962 at a house on Eighth Street in Fargo, North Dakota, and my mom answered. The visitor was from the Welcome Wagon and had some gifts for newcomers to the neighborhood. Among the items in the basket was a little cookbook called “Specialties of the House,” a gift from the North Dakota State Wheat Commission. My mother filed it away with her other cookbooks—none of which I think she consulted, except for the Betty Crocker Bible.

Flash-forward a few decades: The Internet Is Invented! And there was great rejoicing. Connections formed organically as like-minded people found each other. Websites devoted to niche interests flourished. Corporations that wanted to play in the sandbox stood on the margins, unsure what to do. I was keen to do my part, since the internet depended on people putting up stuff for fun or informational purposes, hoping to get noticed by the great searching eye of Yahoo. Every day they had a list: new sites on the Internet! You couldn’t keep up. Why, some days there’d be 15 more sites than yesterday. Science news, geek stuff, maybe something from an educational institution that was keen to rev its engines on this “information superhighway.”

I was determined to provide some content, to use the soulless modern term. But how? There was already a niche interest in “retro” things, along with a brief late-’90s revival of ’60s swank—finger-snapping mambo, lounge music, tiki, the whole hip-dad culture we’d derided growing up but now seemed appealing in the jangly ’90s. I thought a recipe book full of ghastly meals, captured with the pitiless glare of a crime-scene photographer, accompanied by midcentury clip-art, might find a niche.

The result was a website called “The Gallery of Regrettable Food,” and it was soon a Cool Site of the Day, a Yahoo pick and so on. Emails of praise gushed in, sometimes three a week. Well, we’d best do more. This internet isn’t going to fill itself. I found more ’50s and ’60s recipe books in the thrift shops and built the site up until it was a huge collection (50 images, at least) of 320KB pictures and text.

Eventually it would turn into a book, and a sequel. The website’s still up and was last updated in February 2024. On X, when someone posts a picture of a ghastly casserole from the ’40s, I’m tagged in the comments. The other day I discovered a Facebook group called “The Gallery of Regrettable Food,” continuing my life’s work. Once a month, the mail brings a contribution from a stranger, perhaps someone who’s been studying the Gallery for a quarter-century.

But did I perpetuate a lie? Probably.

The Great Food Ad Lie

To figure out the hows and whys of the Great Food Ad Lie, let’s take a look back to the ads of the 20th century.

Let’s start with the food ads of the ’40s: canned hash, digestible lard, ersatz meat with names like “Spam” or “Treet.” Lots of ads for constipation remedies, cautioning the user against harmful purgatives, which apparently were capable of propelling one off the seat and into the door.

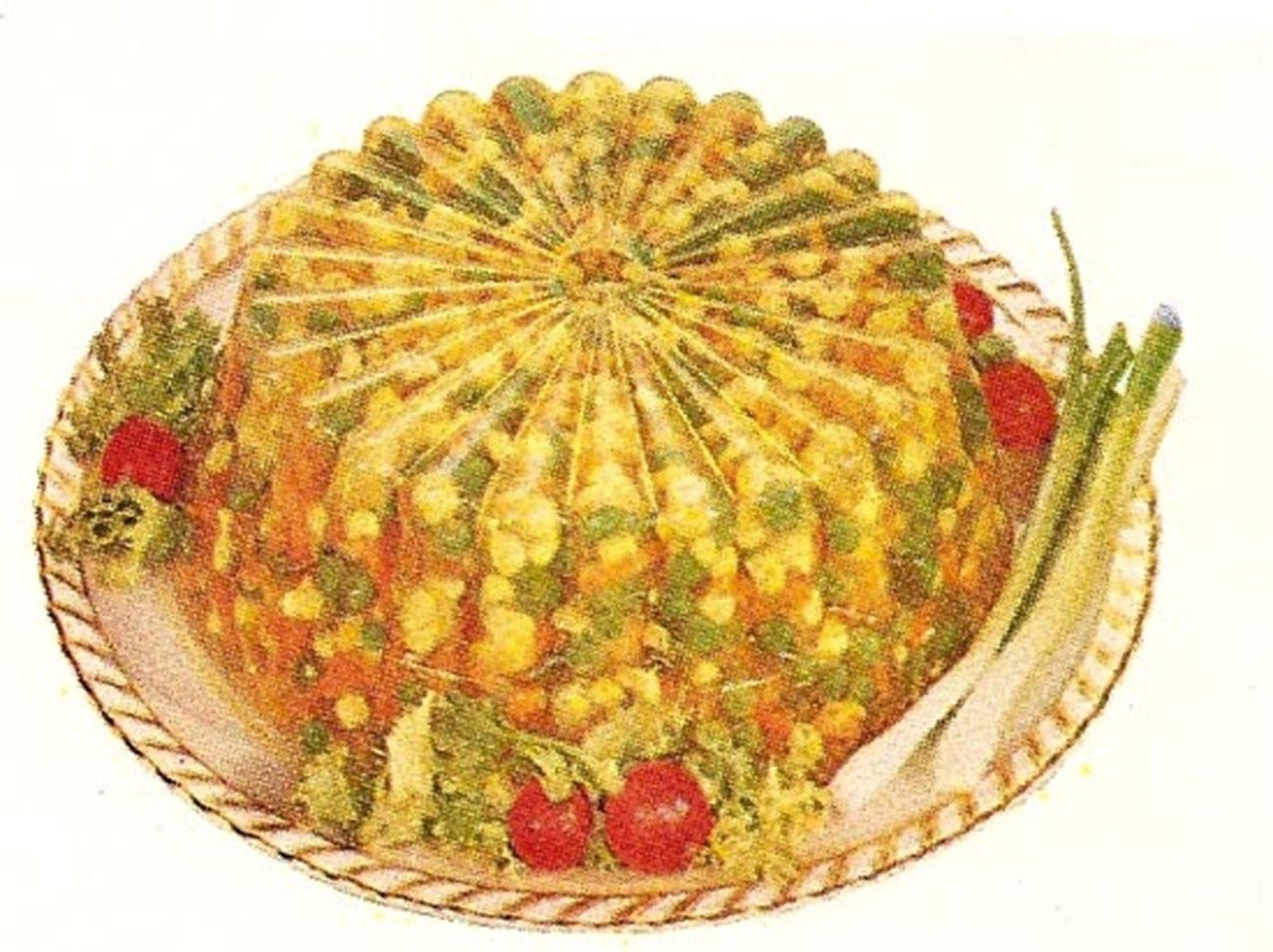

The food was often presented in paintings, intricately composed. The main dish was a glistening mass, surrounded by carefully placed pieces of vegetables everyone tossed away to get to the good stuff. If there was a photograph, it might be a bit stark and grainy to modern eyes. If it was black and white, the juices looked as if the meat was marinated in motor oil. Salmon was often forced into molds against its will and served in oval slabs with protuberances like a Klingon’s skull.

It does not look appetizing, for the most part. Perhaps that explains the lower rate of obesity in those days.

Things changed in the ’50s, when the widespread use of color introduced an era of glorious gustatory abundance. Strangest of all, to today’s viewers, was the mass craze for aspics: shuddering blobs of gelatin poured into elaborate molds, with shaved vegetables suspended in their translucent depths. Aspics were not new, but the ability of the magazines to make food pop off the page gave them a futuristic, well, aspect. Everyone in the ads is happy to the point of delirium, mouths open, eyes wide. Men salivated, housewives beamed with pep-pill brio, children were electric with sugar-frosted cheer.

It still does not look appetizing, for the most part, but it has a certain naive joy, and with cynical modern eyes, we make fun of the people pictured for being so happy over such banal offerings. Compared to the dining options we have in the 21st century—the innumerable importations from other cultures—the food choices of the Regrettable Food era seem scant, the flavor palette limited to a few muted hues. Compared with the commercials we saw on TV in the ’90s, when fresh tomatoes tumbled through spumes of bright water, the food of the ’50s looks processed and unnatural. The images look like they came from a different culture—perhaps because they did.

But there was something about that culture we like even today. Something we miss. It seemed sturdier, more cohesive, confident, cheerful, optimistic. None of that was completely true, but we want it to be. And I had a small part in spreading the illusion.

Our Culture of Half-Truths

As noted above, the early days of the internet reflected the swank revival of the ’90s. It was as if the invention of a medium with infinite possibilities and instant updates was suddenly nostalgic for a time of three TV channels and a daily newspaper. The ’50s and early ’60s, the source material for early internet remixing and meme-mining, were the gold standard for carefree cool. Why? They weren’t really carefree at all. They were fraught and neurotic and fearful, with war and dread of war. But the late boomers, still relevant, remembered the “Happy Days” ’50s revival in the ’70s, and the up-and-coming generation looked with interest at an era that seemed to assume the roles of adulthood with ease.

“The Gallery of Regrettable Food” book had an unfortunate publication date: Sept. 11, 2001. Post-9/11, all the images of domesticity and modernity and cultural confidence that appeared in the book’s ads were like comfort food. When I did interviews about the book, I was told by interviewers how the “Gallery” was passed around in newsrooms during the craptacular days of late 2001. Everyone wanted to look away, and sometimes that took the form of looking back.

When the original website was first published in 1997, the images it discussed were around 30 years old. Now we’re nearly 30 years past the first appearance of the website, and we have no culture to remix but “remix culture.” Everything old seems new again, but nothing is really original. Memes pop up like mushrooms after rain, but they still have the same typeface and format as 15 years ago. Now it’s the fast-food ads of the ’80s and ’90s that seem like a lost culture, a golden era. The reasons are the same: Everyone’s happy, the families at the McDonald’s look solid and content, the framework of America looks strong. Neon and saxophones, spiked hair and Ray-Bans, cars cruising through fog. That, too, is a half-truth.

But we are a culture of half-truths, and that’s our strength. We want to believe in something good about ourselves, even as we know the past was as messy and nervous as our own era. A new internet cohort comes of age and regards the ’90s as an untroubled time, the last ration of innocence. This, of course, is also nonsense, but hey: Better to indulge some childhood memories than insist everyone look at the past as a garden of thistles. If it’s always been a tainted tale, there’s no point in telling it to your kids. It wasn’t all good—no era ever was—but there’s something good we can find and revive.

If that means taking old food ads at face value and believing that Dad and the kids were really, really happy to see a plate of spaghetti, and Mom was truly happy to see them ecstatic over her creation, then fine. What’s the harm? There were happy families. There were happy mealtimes. There was spaghetti for all.

As long as we don’t insist that everyone was delighted to see a cold aspic studded with radishes and celery. That would be a lie, and I’ll have no part in spreading that one.