Art That’s Just for Me

What will the rise of artificial intelligence do to visual media?

I’m working on a book celebrating the work of a commercial artist, Chester Gallsworth Dahleigh—“Chet” to his friends. He signed his most personal work “Petey,” so I suppose Chet G. “Petey” Dahleigh is the proper term. This summer, I plan to release an online collection of his most striking work, an examination of the works he did not for paying corporate clients, but instead rendered in his sleep.

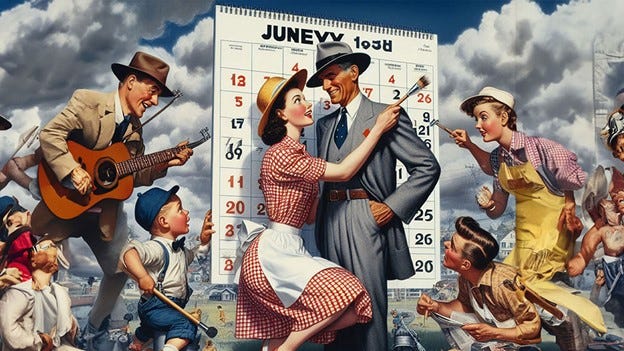

There are hundreds of such works, and they all express a peculiarly cheerful nightmare about American culture in the 1950s.

Some say they’re a result of his wife’s long effort to poison her husband with various herbs and mushrooms from the family garden—a theory bolstered, no doubt, by her conviction for murdering her husband by poison in 1960—but others insist that Dahleigh’s daytime work painting anodyne scenes of commercial joy posed an affront to his talent and soul, and he would rise at night to explore the id of the American dream in the 1950s. In his work, there is always joy:

There’s frequently a flag:

There are often fragments of calendars, because he did many paintings for calendars given away by gas stations and grocery stores.

In the margins, though, are things from Bosch: half-formed creatures, dogs flying through the air, plane-bird hybrids and often a scene of catastrophe in the distance.

It’s a remarkable body of work, and the more you study it, the more the details fight your attempt to bring them into an understandable resolution. They are items from a dream, the things that lurk on the periphery of our brains as they handle the nightly deluge of cleansing electricity. No one ever dreamed anything like Dali painted. But everyone dreams, at some point, of the scenes of Chet G. “Petey” Dahleigh.

Or, if you wish, Chat-GPT Dall-E. He does not exist.

We’ll get back to him in a moment. But first, let us look at the landscape of AI art available to the ordinary folk—or, as a prompt-expert might say, landscape, filled with nerds and dweebs with unnatural interest in Japanese schoolgirl drawings, in the style of Constable.

Creativity ... or Commissioning?

Even the best AI art is boring. You know that someone who’s really skilled at writing prompts came up with something like this:

A portrait of a young woman in Prague wearing a raccoon-fur-lined coat with ivory buttons, harvested responsibly from 1917 piano keys, red Bakelite hairpin with an Art Nouveau design, snowy day, heavy flakes, glowing streetlights based on a metallurgist’s interpretation off an Aubrey Beardsley pen-and-ink drawing, dusk, Leica camera, F-stop of 16, Kodachrome film from 1953, big boobs

The result is that, alright—but so what? It may be stunningly realistic, and it may look nice, but it will have a sense of perfection that makes something in your brain dismiss it: It’s not real. If it’s rendered in the style of a painting, your reaction may be less indifferent, but then you’re reacting to a parlor trick. For my next magic act, I will make a picture of a bear wearing a tutu, riding a unicycle with a small pink parasol, in the style of Vincent Van Gogh. Yep, that’s what it is.

The defenders of AI art—and I’m actually one of them, because I can’t draw either—insist that the creation of a detailed and imaginative prompt is an act of creation. It is not. It is an act of commissioning.

If you’re stumped for what to commission, the Microsoft Copilot Image Creator gives you helpful suggestions: “Try ‘A cat waiting at a bus stop in Tokyo, anime cartoon.’” And that is what you get. Isn’t that great? Cats are awesome! Tokyo is awesome! Anime!!! You could hit the CREATE button and make 60 anime cats waiting for a bus in Tokyo before AI gets tired of you and slows you down.

If you want to generate something interesting, here’s the secret. Less is more. Make the dreaming brain of AI fill in the details you refuse to supply. The results are bizarre in a way no sane human mind could conjure.

Which brings us back to Chet G. “Petey” Dahleigh.

‘Should Be’ vs. ‘Is’

I was trying to craft a prompt to produce a particular kind of mid-century all-American commercial art, and stumbled on something short and simple that produced these unusual visions. I’d make 20 a day. A style emerged, a way of seeing the world, a crazy vision filtered through an apple-pie illustration style. I figured a few people might want to part with a fiver to see what I’d stumbled upon, if I provided some additional amusement in the form of captions and surreal explanations. The forward would be written by a noted European art critic, Lukat D. Sobtexzt, a man noted for finding meaning where all else had despaired. He’d made his reputation when he discovered the Third Meaning of Warhol’s Brillo Box, which critics had theorized for years but never proved. This led to his great Theory of Dark Meaning, an unknown force in the universe that binds bad paintings to the walls of museums all over the world. There is no specific proof of its existence, but it explains why all the Basquiats in the world don’t fall from the nail and hit the floor.

That’s all made-up japery for the book, but when it comes to actual Dark Meaning in AI art, we saw an example in Google’s rollout of its Gemini AI. The program had been hard-coded to diversify your requests, lest your narrow, racist, Western-Civ-centric expectations be satisfied with images that conformed to reality. You would ask for a typical North Dakotan, and be chided: There is no such thing, North Dakota is a diverse place, and here are some examples of Diverse North Dakotans. Hence, a Black farmer, an Asian young woman on a tractor. The internet ganged up on Gemini in a day, hooting its derision, posting an endless stream of Black Vikings and American Indian signers of the Declaration of Independence. This was all intentional. And done for the goodness of the cause, of course, because it’s better to insist that this should’ve been reality rather than produce images that conform with the truth.

The Google engineers never seemed to think this through: If their AI guidelines and guardrails shaped AI art production as much as they wished, and reformed the narrative about the country’s ideal history, then the accusations about American history are auto-debunked by their well-intentioned falsifications. This country has been saturated with white supremacy from the start! Really? Here’s 42 images of Black pilgrims, plus Frederick Douglass Crossing the Delaware for good measure.

A More Custom Future

At this point we should insert the obligatory “growing pains” note, and admit that this is just getting started. Clever people have done interesting and amusing things with AI art. Text-to-video will be a boon for people bored with other people’s movies. I’d love to spend a few weeks writing a story about Captain Renault from “Casablanca” solving a crime. You could make a movie about a young girl who has the most extraordinary day of trial and joy, and at the end she leaves Manhattan on a ferry, and we see Mr. Bernstein from “Citizen Kane” staring at her with a startled look, struck to the core by the sight of her, forming the memory he will tell 40 years later. Not saying you should make that movie, but you could.

And they will. In 10 years, there will be movies about every single person who boarded the Titanic. In the style of Robert Altman. In the style of Martin Scorsese. In the style of Steven Spielberg. There will be 100,000 fan-fic Star Wars movies as bad as the TV shows, all starring the person who dictated the scenario. There will be a subculture of people who exhaust the creative world of “Twin Peaks” with endless vignettes, and one or two will get it exactly right. In the end, we will watch our own movies more than others, and the theatrical experience will have gone from the great shared silver screen in the communal dark, to niche streaming, to watching our own particular curiosities and desires played on our own glowing rectangles. Millions of hours of movies, made for an audience of one.

Oh, and the AI music generators will provide the soundtracks in the style you prefer. Siri, fabricate a remake of “West Side Story,” condensed, tighter third act, with Oompa-Loompas and Muppets instead of Sharks and Jets, in the style of Sam Peckinpah, with a score by Devo. I open myself to ridicule when I say we could have this in 10 years, when we all know it’ll just be five.

Or next year. I hope so. When my book on Dahleigh comes out, I’d like to have a full video biography ready to go. In the style of Ken Burns, of course.