Are Some Forms of Populism More Equal Than Others?

In ‘Democracy Unmoored,’ Samuel Issacharoff notes the ill effects of populism but fails to diagnose its true causes

The populist wave that has swept the world in the past decade is in some respects a Rorschach test. That’s unsurprising; social trends are usually so complicated and contingent that generalizing from one society to another, or even one time period to another, is fraught. Did Donald Trump’s razor-thin 2016 victory truly mark a realignment in American politics? Or was it a fluke, caused in part by voters’ distrust of Hillary Clinton? The answer is some combination of both, of course. What’s more, candidates change once elected, thanks to the incentives they face in office, and they, in turn, change the establishment in ways that can’t be reversed. Thus, in analyzing the rise of populism, academics face a tough challenge—one they can only hope to overcome by laying aside their own political prejudices and thinking objectively in principled terms.

Unfortunately, Samuel Issacharoff fails to do that in his new book, “Democracy Unmoored.” As a result, the book—whose laudable goals are to understand the erosion of democratic institutions and offer suggestions for reinforcing them—ends up being so blinded by its own assumptions that it becomes almost an example of the problem. The populist wave is motivated, at least to an important degree, by a revolt against precisely the kinds of political orthodoxies to which Issacharoff unreflectingly adheres—and as a result, his analysis suffers from the unconscious smugness typified by the legendary Manhattan journalist who, after Richard Nixon’s 1972 landslide, said she couldn’t understand that outcome since nobody she knew had voted for him.

Populism for Me, But Not for Thee

Consider Issacharoff’s casual assertion that anyone looking for proof that democracy can fail “need not look further than the United States’ inability to muster an accepted public health mandate for [COVID] vaccination.” It hardly crosses his mind that there were reasonable arguments against such mandates—arguments that, even if wrong, are not self-evidently “failures” of democracy.

Or consider his remark on the loss of trust in the news media (one of only a handful of sentences that even mention this vital aspect of populism in America). “The desire to retrench amid the familiar is a commonplace reaction to social and economic insecurity,” he writes. “Thus is born the charge of ‘fake news.’” Well, no. For decades before Trump’s election, the American media’s overwhelming leftward bias and willingness to distort and falsify facts to serve that bias more than earned the public’s distrust. Issacharoff could have acknowledged that the media squandered their credibility in the years before 2016 while still arguing that the lack of mutually accepted news sources is a grave danger to democracy. Instead, he takes the patronizing route.

Despite these shortcomings, “Democracy Unmoored” does contain some insightful observations on the causes of populism. In Chapter 2, for example, Issacharoff compares China’s rapid construction of Beijing Airport’s impressive Terminal 3 with London’s slow building of Heathrow’s boring Terminal 5 and the snail’s pace of the still-uncompleted renovations at New York’s LaGuardia. China’s accomplishment, of course, is typical of totalitarian dictatorships, which can sometimes act rapidly since they need not concern themselves with human lives or welfare. Stalin built beautiful subway stations, too, and Germans still enjoy Hitler’s autobahn. But as Issacharoff notes, the world’s public often gets distracted from the cost side of that equation, and “instead what emerges [in the public mindset] is the capacity of Chinese authorities to simply get the job done.”

That impression then leads people in the democratic world to hanker for strongmen who can likewise cut through the “gridlock” of democracy and simply impose their will. Thus American businessmen in the 1930s toasted Benito Mussolini for “making the trains run on time.” In Issacharoff’s terms, democratic citizens frustrated by government inaction begin to lust for a “caudillo” who will use “individual charismatic authority both with the populace and the military” rather than obeying the rule of law.

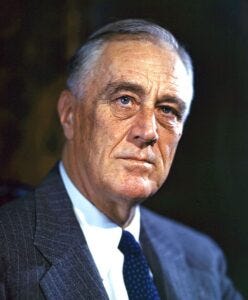

Issacharoff is right about this phenomenon, but to follow it to the root, one would have to address fundamental principles, and in particular to discuss the proper role of government—and Issacharoff declines to do that. A hint as to why can be found in his decision to focus on the breakdown of respect for democratic institutions in the period since 1945. That year might seem an obvious starting point—many social analyses start there—but it’s also a misleading one because in 1945 the United States stood at the apex of collectivist social and economic policies implemented by a supremely populist-authoritarian figure: Franklin Roosevelt, who, as de facto president-for-life, had implemented a version of the Leadership Principle so pervasive and transformative that, like the fish who’s never heard of water, Americans still don’t grasp its enormity.

Populism’s Roots Go Deeper Than 1945

Roosevelt was, in fact, America’s most successful populist demagogue. After declaring the Constitution a “superseded” relic of a “horse-and-buggy era,” he ruled largely by executive decree; managed an unprecedented bureaucratization of the country; created a Federal Communications Commission (all of whose members he appointed) with power to restrict what could be said on the radio; oversaw the condemnation of vast tracts of land for prestige projects such as the Tennessee Valley Authority; empowered labor unions to impose confiscatory demands on employers; implemented a version of fascist corporatism called the National Industrial Recovery Act, which placed the entire nation’s economy under his personal control; nominated every Supreme Court justice but one; and sent more than 100,000 Japanese Americans to concentration camps. He was as anti-institutionalist as they come—although he preferred to call his contempt for institutions “bold experimentation”—and he was nothing if not a populist.

Although World War II helped divert the energies that might otherwise have brought about full-fledged fascism in America, Roosevelt nevertheless managed to obliterate some of the nation’s most cherished institutions—not least the convention against a third presidential term—and to erect a new political system in which the government was not the people’s servant but their guardian, caretaker and warden. And he did it with such deft populist appeal that he remains a folk hero today, notwithstanding the cynical incoherence of his economic and political philosophy.

Consequently, to start one’s analysis of the populist assault on American institutions in 1945 is misleading, because it presumes that the New Deal legacy is the baseline and that deviations from it constitute the “undermining” of “stable” conventions. Issacharoff’s sole comment on this, however, comes in the introduction. After asserting that Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech “redefined international relations by inviting competition over the ability to provide enhanced social welfare for the citizenry,” he pauses for a flippant dismissal of Roosevelt’s critics: “Market apostles such as Friedrich Hayek and backers in the banking class,” he writes, “still hearken[ed] for the Gilded Age.” Then he moves on.

What Is Government Failure?

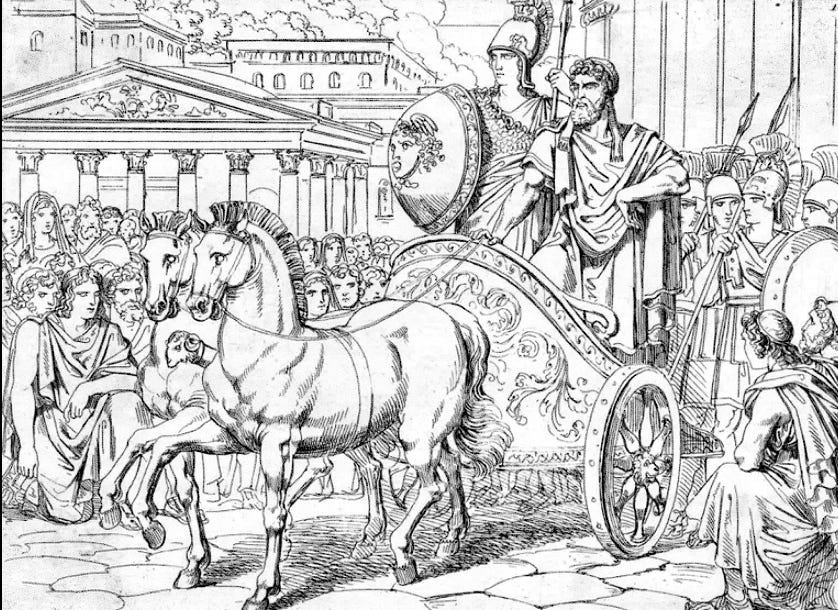

The problem here isn’t Issacharoff’s blithe discounting of Roosevelt’s opponents. It’s that his refusal to fairly weigh their criticisms indicates a failure to think in terms of principles—a failure that blinds him not only to the populism at the heart of the very institutions he thinks crucial to democracy, but also to other significant elements of populist authoritarianism, which, after all, is no new thing. Since at least the days of Greece and Rome, politicians have manipulated the people with promises of bread and circuses and appeals to their xenophobia.

In the sixth century B.C., Pisistratus rode into Athens in a chariot beside an actress dressed as Athena, to wow the hoi polloi into thinking he was divinely selected for dictatorship. Episodes like that were precisely why the classical liberals who founded the United States fashioned a constitutional state instead of a pure democracy. They did so with a clear eye to the underlying principle that democracy is legitimized, and thus necessarily limited, by deeper principles of individual liberty—principles we flout at our peril.

Issacharoff makes no mention of this. Instead he asserts that “a well-functioning democratic state should offer citizens a sense of individual dignity emanating from control over their political fate and a sense of collective gain from an accountable state delivering material improvements over time.” He maintains that “wrest[ing] popular support for democracy back from authoritarian demagogues” depends on proving that democracies can give people a “sense of common mission” by engaging in public works projects such as railroad construction and green energy programs.

But the authors of the Constitution believed the opposite: that a properly designed state would preserve freedom by so severely restricting what citizens could accomplish through politics that they would concern themselves with productive private-sector undertakings instead. The American Constitution’s legitimacy rests not upon a desire for government munificence, but on the wish, as George Washington liked to say, for the freedom to rest under one’s own vine and fig tree, with none to make him afraid.

Failure to recognize this distinction explains the otherwise stunning fact that nowhere in his 286 pages does Issacharoff mention the nationwide riots of 2020, which helped set the stage for the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol Building. In virtually none of his long passages on the breakdown of what he calls “government delivery of social goods” does he focus on simple law enforcement. Yet history reveals that fascism grows in proportion to government’s failure to protect citizens from theft and assault. Whether it be the Brownshirts of Weimar or the Black Panthers in Oakland, such movements typically start as vigilante groups, gaining popular support by appearing as protectors of the public.

The failure, or refusal, of local officials to take action against riots in Minnesota, Portland, Seattle, Wisconsin, etc.—or even such precursors as the violent protests on Inauguration Day 2017, or the storming of the Capitol during Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings—certainly lent credence to populist claims that democratic institutions had broken down and that only a populist strongman could restore justice. And that was surely more significant to recent populist trends than federal failures regarding “the space program or . . . highway investments.”

The Administrative State—Bastion of Democracy?

Ignoring the classical principles of liberalism renders “Democracy Unmoored” incoherent in another way. Consider Chapter 2, in which Issacharoff argues, rightly, that the diminishing significance of legislatures is one key cause of populist authoritarianism. In theory, contemporary democracies are legitimate partly because their laws are produced by reasoned deliberation among elected representatives. Yet Congress and parliaments worldwide do less meaningful debating now than ever before, and they play a vanishingly small role in the actual formation of policy, which is instead created by unelected bureaucracies or executive orders. This is another Roosevelt legacy, and it understandably draws voters to “executive unilateralism” like moths to a flame because now the executive, rather than the legislature, gets things done.

Yet in Chapter 8, Issacharoff bemoans the public’s growing hostility toward administrative agencies, claiming that this is also a basic cause of democracy’s ills. Indeed, he describes the bureaucracy in heroic terms—lauding it for its “institutional resistance to autocratic rule”—and reserves some of his harshest language for President Trump’s assaults on these agencies. Trump’s anti-bureaucratic efforts were, however, anything but undemocratic. A considerable proportion of his support came from people fed up with the imperiousness of administrative “experts,” who, without democratic accountability or constitutional legitimacy, purport to tell them how to live their lives. Issacharoff, however, brushes away that resentment as merely the “antiregulatory demands of well-heeled enterprises.”

“Bureaucratic authority rests on a normative commitment to resist the politics of the moment in favor of the dictates of expertise, experience, and reasoned study,” he contends—and that’s certainly the theory. But the reality is that administrative agencies are subject to pressure by special interest groups, which is why they’re a major cause—perhaps the major cause—of government dysfunction in the United States today. It is administrative agencies that, for example, empower ideological minorities such as NIMBYs and environmentalists to halt construction projects voters desire, or enable the president to pursue his own wishes even when Congress says no—as with President Obama’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans program or President Trump’s spending of money on the Mexican border wall despite Congress denying him that funding.

There’s nothing wrong with voters objecting to those executive actions, and Issacharoff could have acknowledged the threat to constitutional rule that agencies represent without undermining his broader argument. Instead, he lionizes bureaucracies—which turns his critique of anti-democratic authoritarianism into merely a condemnation of that anti-democratic authoritarianism which he doesn’t like. You cannot simultaneously regard the administrative state as a bulwark of democracy and complain of the decline of legislatures, or of the likelihood that voters will seek an executive willing to drastically change administrative rules. Issacharoff—who thinks “the language of human rights poorly captures” the nature of today’s populist threat—complains emphatically about politicians using “intralegal mechanisms to wear their opponents down.” But the Constitution creates “intralegal” mechanisms precisely to empower politicians to wear their opponents down. They’re called checks and balances.

A Way Out?

Issacharoff’s muddled thinking on these subjects carries over into the reform proposals at the book’s conclusion. He comments on various methods of fact-checking news sources on social media, but rightly stops short of endorsing any of these vaguely formulated proposals, especially any that might empower the government to censor speech. He suggests establishing something in Congress to mimic Britain’s “shadow cabinet,” thereby increasing the opposition party’s ability to hold the majority accountable—but also acknowledges that this can “frustrate the [majority’s] effective capacity to govern,” as if that were a bad thing.

His most interesting idea is to “abandon the current system of campaign finance,” which not only empowers incumbents and distorts the expression of political preferences by channeling money through obscure PACs, but also reduces the ability of political parties to discipline their own candidates: “Better to have the money flow to the parties and through them to provide some protection to less extreme candidates who now fear donor retaliation.”

But in the end, the pathologies Issacharoff describes can only be cured by a change in public attitudes. Populist demagoguery and fascism are probably the default state of human politics. The only way out is the one America’s Founders took: an agreement to respect fundamental principles of personal liberty that the state cannot transgress. The erosion of that consensus is the root cause of our political illnesses today.

Writing of the mores—the social habits—that constrain democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville remarked that “the law permits the American people to do everything, [but] religion prevents them from conceiving everything and forbids them to dare everything.” But for well over a century, religion and its substitutes—most notably, reverence for the classical liberalism of the American Constitution—have increasingly failed to play that role, and they are under explicit assault today from both left and right. As a result, voters are encouraged to dare everything by exploiting the state’s coercive powers to impose their will on others. To repair our institutions and stave off the fate of so many other failed democracies, we must first restore our commitment to mutual respect for individual rights.