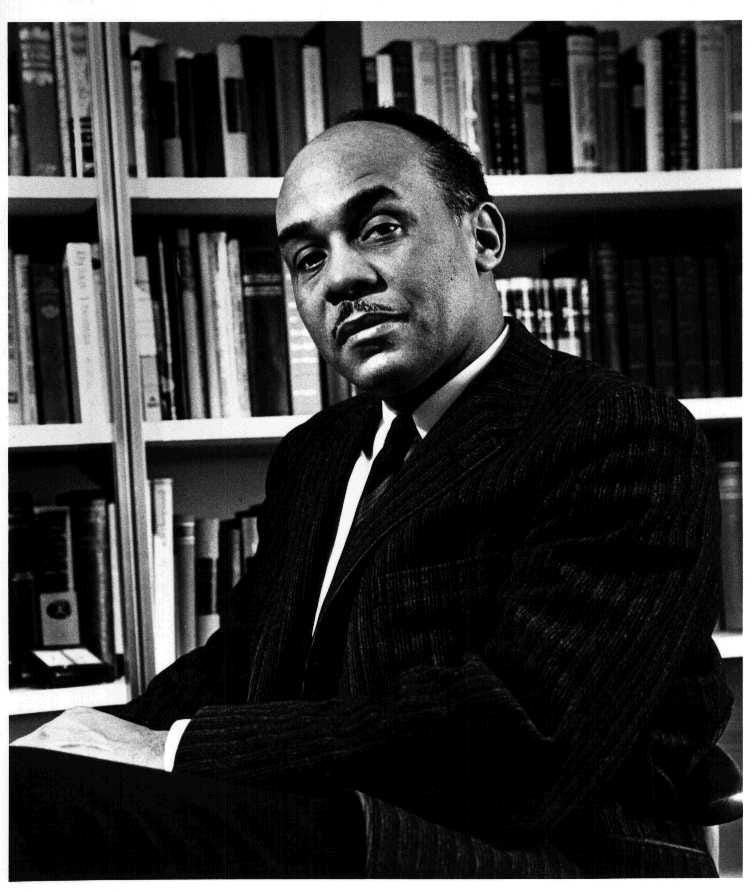

Appreciating Two Icons of American Idealism

Ralph Ellison and his piano teacher, Hazel Harrison, offer us an inspiring vision of America’s future

It may seem naive to extol the ideals of our liberal democracy at a time when that system is being put to the test. The 2024 election will not be the first time those ideals have been tested, nor will it be the last. But given the challenges we face, we must articulate what’s at stake and what we’re trying to preserve. As I wrote in an earlier commentary in the wake of the events of January 6, 2021, I am not sure I know another way forward for my family, my community or the nation.

My inspiration in revisiting these ideas comes from what may seem an unlikely source—but it’s a voice that represents a high-water mark in the discourse about pluralism and its centrality to the concept of Americanness. It turns on the response of a now-famous Black writer to a bit of unwelcome advice that he was given by a Black concert pianist and teacher 30 years his senior. Both had every reason to doubt America’s promise and to exchange their future hope for present anger. And it links one tumultuous era, the 1930s, with another, the 1970s, as they both looked forward in hope to brighter futures. Fortunately for us, his memorialization of her advice—his riff on her tonic chord—stands as one of the finest paeans to the ideals of the American republic.

The Writer and the Teacher

The writer is Ralph Ellison, who wouldn’t write his best-known work, “Invisible Man,” for another 20 years. He took up the trumpet at the age of eight and, having grown up in the Deep Deuce District of Oklahoma City, heard firsthand the likes of jazz greats Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Count Basie. In his early 20s, he enrolled at the Tuskegee Institute to study music. On one occasion, he wallowed in some harsh criticism of his performance at a student recital. But his teacher, Miss Hazel Harrison, wasn’t having any of it.

Harrison, by her mid-50s, had had a remarkable career that took her from the Midwest of the 1880s to Northern Europe at the turn of the century, playing Chopin and Grieg for the Berlin Philharmonic in 1904 at the age of 21. She knew many of the masters of classical music, including Sergei Prokofiev and Percy Grainger. The full story of her eventful life has yet to be written. But we do know that she left Germany in 1931, in response to the ominous rise of Adolf Hitler. She had, one might say, seen a thing or two in her lifetime. And she was unphased by the young upstart Ellison’s easy disappointment.

Harrison told young Ellison to buck up: “You must always play your best, even if it’s only in the waiting room at Chehaw Station, because in this country there’ll always be a little man hidden behind the stove. ... There’ll always be the little man whom you don’t expect, and he’ll know the music, and the tradition, and the standards of musicianship required for whatever you set out to perform!”

Ellison was initially “disappointed and puzzled by Miss Harrison’s sibylline response,” but he “respected her artistry and experience too highly to dismiss it.” He allowed himself to yield to her hard-earned authority. “As I leaned into the curve of Miss Harrison’s Steinway and listened to an interpretation of a Liszt rhapsody,” he writes, “the little man of the Chehaw Station fixed himself in my memory.” The riff that follows leads him to a breathtaking vista of the American experience that I can only compare, musically, to Antonín Dvořák’s “New World Symphony” (also composed, perhaps not coincidentally, by an outsider).

The essay that this exchange sparked, “The Little Man at Chehaw Station: The American Artist and His Audience,” was published in the Winter 1977/78 issue of The American Scholar, then edited by Joseph Epstein. Only Ellison can take you on the Grand Tour from point A to point B, but it’s worth a glimpse at the destination and to consider if, some 46 years later, we’re any closer to the future that Ellison hoped for.

The Whistle Stop

Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Ralph Ellison (says the announcer introducing the soloist):

Why would Hazel Harrison associate her humble metaphor for the diffusion of democratic sensibility with a mere whistle-stop? Today I would guess that it was because the Chehaw Station functioned as a point of arrival and departure for people representing the wide diversity of tastes and styles of living. Philanthropists, businessmen, sharecroppers, students and artistic types passed through its doors. But the same, in more exalted fashion, is true of Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Museum; all three structures are meeting places for motley mixtures of people. While it might require a Melvillean imagination to reduce American society to the dimensions of either concert hall or railroad station, their common feature as gathering places, as juncture points for random assemblies of sensibilities, reminds us again that in this particular country even the most homogeneous gatherings of people are mixed and pluralistic. Perhaps the mystery of American cultural identity contained in such motley mixtures arises out of our persistent attempts to reduce our cultural diversity to an easily recognizable unity.

Here Ellison recognizes the breadth and diversity of the American population, noting that people of various income, social standing, national origin and educational attainment rub elbows with each other in their shared public spaces. Further, as Harrison pointed out, any one of the crowd of people in Chehaw Station could be the ideal audience for Ellison’s art, regardless of that person’s social status. Chehaw Station thus becomes a practical expression of the ideals set forth in our nation’s founding documents. Ellison continues:

The rock, the terrain upon which we struggle, is itself abstract, a terrain of ideas that, although man-made, exerts the compelling force of the ideal, of the sublime: ideas that draw their power from the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. We stand, as we say, united in the name of these sacred principles. But indeed it is in the name of these same principles that we ceaselessly contend, affirming our ideals even as we do them violence.

As a Black man in the mid-20th century, Ellison was keenly, personally aware of how far the U.S. was falling short of these “sacred principles” when it came to the issue of race. While he embraced the Founders’ vision, he knew that equality for all people under the law was still an ideal, not a reality.

For while we are but human and thus given to the fears and temptations of the flesh, we are dedicated to principles that are abstract, ideal, spiritual: principles that were conceived linguistically and committed to paper during that contention over political ideals and economic interests which was released and given focus during the period of our revolutionary break with traditional forms of society, principles that were enshrined—again linguistically—in the documents of state upon which this nation was founded. ...

As a nation we exist in the communication of our principles, and we argue over their application and interpretation as over the rights of property or the exercise and sharing of authority. As elsewhere, they influence our expositions in the area of artistic form and are involved in our search for a system of aesthetics capable of projecting our corporate, pluralistic identity. They interrogate us endlessly as to who and what we are; they demand that we keep the democratic faith.

Ellison’s essay offers far more than I can possibly convey in this short space. Among other things, it contemplates the character of the “little man” in greater depth; considers its implications for artists and writers; describes the limits of Fitzgerald’s moral imagination in “The Great Gatsby”; and questions the aptness of the “melting pot” metaphor for the “cacaphonic motion” at the heart of Ellison’s America. I offer the selections above with the hope that you will seek out the essay in its entirety in “The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison.”

Pursuing Ellison’s Vision

Read from the vantage point of 2024, we have no trouble producing dozens of reasons to doubt that the America Ellison extols still exists. Ellison himself seems to understand that the “little man” represents a set of contingencies that may be too easily extinguished.

“These individuals,” he writes, “seem to have been sensitized by some obscure force that issues undetected from the chromatic scale of American social hierarchy. … It would appear that culturally and environmentally such individuals are products of errant but sympathetic vibrations set up by the tension between America’s social mobility, its universal education, and its relative freedom of cultural information.”

Half a century later, does America offer the social mobility, the education and the access to music and the arts to nourish the souls of Americans? Despite the troubling trends that exist leading into the 2024 election, I hesitate to provide an answer here, because other “sympathetic vibrations,” unforeseen by Ellison, may provide fertile conditions for unexpected growth. Some promising signs might include multiculturalism, increases in Black and minority college enrollment and the astonishing depth and variety of influences on music, literature and the arts since the late 1970s.

The question for us today is, it seems, whether we submit to easy discouragement at the many challenges we face or rise to standards of excellence set by Miss Harrison. If she did not despair, neither should we. If she did not let her anger and disappointment turn into resentment, neither should we.

Harrison and Ellison offer us a way forward. Their example demands that we “keep the democratic faith,” as we each find our own Chehaw Stations—moments of expectation and faithfulness, without platform or audience, at the crossroads.