Amidst "Techlash," Many Americans Still View Technology Industry in a Positive Light

By Adam Thierer

Recently, many politicians, journalists, and others have been talking a lot about a “techlash” against Silicon Valley giants from which only government intervention can deliver us. However, Americans hold technology companies and technological innovation in relatively high regard, while they view the government in a much less favorable light.

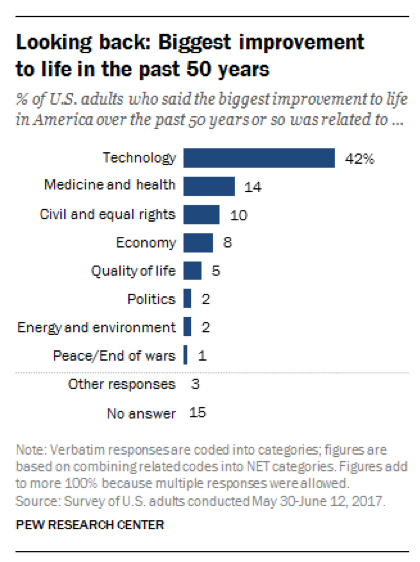

Source: Pew Research Center, "Four-in-ten Americans credit technology with improving life most in the past 50 years."

Recent polling shows that negative attitudes about big tech on the part of political leaders and the press are not necessarily shared by the general population. In late 2017, for instance, the Pew Research Center conducted a poll asking, “What would you say was the biggest improvement to life in America over the past 50 years or so?” The largest share of respondents (42 percent) said technology had contributed more than any other factor. That was three times more than the number of people who responded “medicine and health” (14 percent), which was the next most popular answer. (Incidentally, “politics” came in sixth place, with just two percent of the vote.)

A more recent Pew poll conducted in July of 2019 finds that the share of Americans who believe that technology companies have a positive impact on the United States has fallen from 71percent to 50 percent over the past four years. That’s troubling for tech companies and could be an ominous sign that the “techlash” is intensifying.

But this decrease in favorability may be part of a larger trend: that same poll reveals that American attitudes about other institutions, including churches, colleges, and the media, have also fallen off in recent years. Moreover, despite the drop in positive attitudes, 50 percent of Americans still believe tech companies have a positive effect. That puts tech companies at second place, just behind churches and religious organizations.

Recent data from Morning Consult reveals similar trends. In a new report called The State of Consumer Trust, they find that the technology industry ranks second only to the food and beverage industry in terms of consumer trust.

Source: Morning Consult, "State of Consumer Trust"

And even as many Americans express skepticism of large corporations, the share of people saying that they trust the tech giants Amazon (39 percent) and Google (38 percent) is only outdone by the share of people who trust their primary care doctor (50 percent) and the military (44 percent). According to the poll, Amazon and Google are even trusted more than Tom Hanks (34 percent), Oprah (27 percent), Warren Buffett (16 percent), and religious leaders (15 percent).

Source: Morning Consult, "State of Consumer Trust"

Meanwhile, trust in government continues to fall steadily, according to the Morning Consult report and various Gallup polls. For instance, Gallup reports that a decade ago, 49 percent of Americans had a “fair amount” of trust in the federal government when it comes to handling international problems, while 28 percent had “not very much.” Today, only 40 percent of Americans have a fair amount of trust in the federal government while the number of those with “not very much” trust in the federal government has grown to 37 percent. Pew polling data tell an even starker tale, with only 17 percent of American adults in 2019 saying they trust the federal government all or most of the time.

There are likely many reasons why public faith in government has fallen, but the chronic dysfunction of modern political institutions and procedures may have something to do with it. In his 1999 book, Government's End: Why Washington Stopped Working, Jonathan Rauch coins the term “demosclerosis,” which describes “government’s progressive loss of the ability to adapt”: “[A]s layer is dropped upon layer, the accumulated mass becomes gradually less rational and less flexible.”

Sadly, demosclerosis is the norm in the United States now. Even many working inside the legislative branch agree that government has largely lost its ability to adapt to technological changes. An August 2017 survey by the Congressional Management Foundation finds that “overwhelming majorities of senior congressional aides believe Congress is not equipped to execute its basic functions.” The most cited areas of concern deal with the lack of both the skills and abilities as well as adequate time and resources “to understand, consider, and deliberate policy and legislation.”

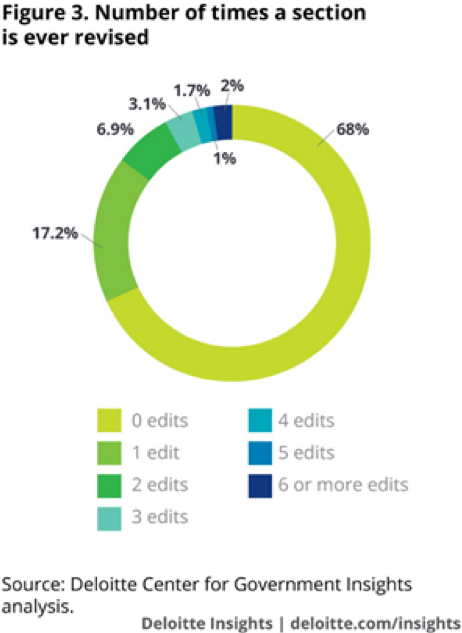

In this environment, legislators have outsourced their duties to administrative agencies, allowing the proliferation of a web of bureaucratic red tape. A 2018 Deloitte survey of the US Code of Federal Regulations reveals that 68 percent of federal regulations have never been updated and 17 percent have only been updated once. Imagine if a business never updated its business model. It would likely eventually go under as the world around it changed. But that does not usually happen for regulatory agencies. The world changes, but they don’t, and their rules don’t.

Source: Deloitte Insights, "The future of regulation: Principles for regulating emerging technologies"

For the technology sector, growing government dysfunction and increasing red tape present real challenges because regulatory accumulation and bureaucracy increasingly undermine the ability of technology companies to innovate and provide more of the goods and services that Americans have come to expect. This growing problem may be one reason why people have lost some confidence in big tech.

In a recent policy brief for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, economist Arthur Diamond argues that regulatory accumulation is a primary cause of the technological stagnation Americans have already seen in many other industries over the past few decades. For instance, reforming barriers to healthcare innovation could help expand access to new devices and services and produce better health outcomes. Transportation and energy sectors would also benefit from less red tape and more technological innovation.

For Diamond, the strongest case for an open market economy is that it allows “innovative dynamism,” which creates massive gains to human betterment. Indeed, this sentiment appears to be reflected in polls like those mentioned previously that illustrate how much technological innovation matters to most Americans. Support for technological innovation would probably be even higher if, as Diamond recommends, policymakers took steps to open up even more opportunities for change, which would lead to substantial progress in many sectors that desperately need it.

In technological innovation, as with many other facets of life, the past is likely to become prologue. The coming years and decades, like those of the past, will bring the world life-enriching technology, so long as excessive red tape doesn’t hinder it. And if this innovation is allowed to flourish, it’s likely that the share of Americans with positive views of the tech industry will return to, or even exceed, its earlier, higher level.