American Alliance Building in the Indo-Pacific and the Calculus of Deterrence

The U.S. is preparing for possible Chinese military action against Taiwan by expanding and strengthening its alliances in the Pacific

By William Roberts

The United States and Australia just conducted a massive joint military exercise in and around the Coral Sea that involved 30,000 troops with forces from 11 other nations including, Japan, Germany, Canada and, for the first time, Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Tonga. Called “Talisman Sabre,” the biennial war game, which ran from July 22 to August 4, modeled what the Pentagon calls a “high-end conflict” with a “peer adversary,” which in the Indo-Pacific can only mean one country—China. The exercise served both as a reminder of the challenge China presents in the Indo-Pacific and a demonstration of the increasing tempo of U.S. military operations in the region with a widening circle of allies and partners.

U.S. Marines focused on island-hopping and dispersal maneuvers to avoid becoming targets of Chinese air power and missiles. Not surprisingly, a Chinese spy ship monitored the exercises off the east coast of Australia.

“We share a common vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific, and we’re committed to investing further in our alliance to uphold this vision,” Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said in a meeting with Australian officials held during the exercise. As part of this investment, the U.S. is upgrading air bases in Australia’s Northern Territory and adding maritime patrols and reconnaissance flights, all designed to strengthen its ability to respond to a potential “crisis.”

Meanwhile, President Joe Biden will host South Korean President Yoon Suk-Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida at Camp David on August 18 to finalize plans for trilateral security cooperation in the Pacific. The three have met frequently on the sidelines of other international meetings, but the three-way summit will be a historic first among heads of state of the U.S., Japan and South Korea.

Long-held animosities over Japan’s brutal military occupation of Korea through much of the first half of the 20th century have traditionally prevented Tokyo and Seoul from pursuing military cooperation. That now is changing. Japan and South Korea both face a dangerous new nuclear threat from North Korea. But China is the major concern, evidenced by recent discussions White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan had with his Japanese and South Korean counterparts in Tokyo on strategic coordination in the East and South China seas and stability in the Taiwan Strait.

The expanding military exercises and diplomacy are all part of a broader drive by the Biden administration to rebuild U.S. coalitions and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific in order to counterbalance an increasingly aggressive China. Motivating the activity is fear China is preparing to take military action against Taiwan. But will the flurry of recent coalition building by top U.S. officials be enough to serve as a deterrent against a feared conflict over Taiwan? President Biden has expressed optimism. Analysts are more skeptical.

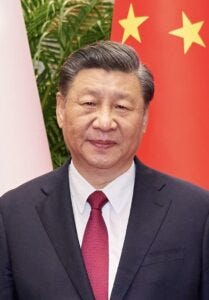

“Don’t worry about China. I mean, worry about China but don’t worry about China,” Biden said at a campaign fundraiser in California in June of this year. “It’s going to take time,” the president said, referencing U.S. coalition building in southeast Asia. But, Biden added, his optimism about Chinese intentions is warranted because President Xi Jinping is “in a situation now where he wants to have a relationship again.”

Meanwhile, Xi’s declaration he wants the People’s Liberation Army to be capable of taking Taiwan by force as soon as 2027 has set off alarm bells at the Pentagon and in Congress. As a result, the U.S. Navy is overtly preparing for a limited war with China sometime in the next 10 years, if not sooner. Yet, many in U.S. military and intelligence agencies assess the U.S. are unprepared for conflict with a rising China.

“We are facing changing strategic conditions. The ones that we were comfortable with for a good 20 to 30 years after the Cold War, they’re not around anymore,” Ja Ian Chong, an associate professor of international relations at National University of Singapore, said in an interview.

According to Chong, “Deterrence, like any strategy, can fail or might not work as intended. And in that event, the U.S. and its allies will have to decide whether they back down and lose credibility, or … step-up, demonstrate resolve. And potentially, it doesn’t have to be a war. It just has to escalate to a highly tense blockade situation.”

War Over Taiwan?

The quandary the U.S. faces with China in the Indo-Pacific now is that even a “limited” conflict over Taiwan, while probably short, would be devastating for both American and Chinese forces. The U.S, Taiwan and Japan could push back a Chinese amphibious invasion of Taiwan but at a cost of two aircraft carriers, dozens of other ships, hundreds of aircraft and tens of thousands of U.S. servicemen and women, according to wargame scenarios run in January by the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS). “The United States needs to strengthen deterrence immediately,” CSIS warned.

Fortunately for now, there are good reasons to think President Xi will not decide to invade Taiwan or impose a blockade anytime soon. Such an aggressive move, even if it succeeded, would likely polarize regional trade partners Australia, Japan and South Korea against China and result in painful economic sanctions from the U.S. and Europe. Xi’s ambitions of building China into a global leader would be short-circuited, perhaps irreparably. And the economic damage to an already slowing Chinese economy would be widespread and devastating.

Xi’s intentions, however, could change over time. Reunification with Taiwan is a key piece of Xi’s agenda for the “rejuvenation” of China. It has been a goal of the Communist Party since the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949.

Lately, Xi’s government has stepped up its efforts to isolate Taiwan internationally and is increasingly conducting gray-zone warfare tactics in and around Taiwan. These include, People’s Liberation Army aircraft venturing across the midline of the Taiwan Strait into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone. A year ago, in protest of then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, China also simulated strikes on the island with live-fire drills. And in April, after Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen visited the U.S., PLA forces demonstrated blockade maneuvers.

Further fanning the flames, Beijing authorities released a new television documentary in early August titled “Chasing Dreams” showcasing the PLA’s new power. It features testimonials from soldiers who say they are willing to die in an attack on Taiwan.

Analysts fear a combination of rising Chinese nationalism and a reversal of China’s economic growth prospects, could push Xi and the Chinese Communist Party to move on Taiwan. With public sentiment in favor of taking Taiwan by force, Beijing may decide it can no longer delay acting with the idea that taking Taiwan would distract from the party’s economic and other failings.

“Washington must bear in mind that the one-China principle is non-negotiable. The Taiwan question is at the heart of China’s core interests,” Xi told Biden when the two met on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Bali in November. It is “Beijing’s first red line,” Xi said, according to Chinese state media.

Beijing’s goal has been to coerce and cajole Taiwan’s population into agreeing to reunification, although that does not appear to be working. Taiwan’s people are moving away from reunification and toward a separate Taiwanese identity, a trend that has accelerated following Beijing’s crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, Taiwan’s nationalist Democratic Progressive Party is leading in polls ahead of the China-friendly Kuomintang Party and third-party Taiwan People’s Party going into January’s presidential election.

The danger here is that Xi and the Communist Party will conclude Taiwan cannot be regained peacefully through politics, and force will be necessary. What’s more, it’s increasingly clear Xi wants to have a credible option to take the island, at the very least to forestall an overt move by Taiwan toward independence.

Building Coalitions in the Region

For President Biden and his team, this situation means the U.S. must rely on statecraft tied to rapid improvements in military posture to maintain peace and stability in the region. As a result, the U.S. has been rapidly shoring-up and expanding alliances with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific. “The Biden administration, as part of their response to Xi preparing for war, is reinforcing our relationships with allies and partners where, if we need to be present for a military scenario, we can be present and we won’t be alone,” said Michael Sobolik, a senior fellow in Indo-Pacific studies at the American Foreign Policy Council.

But diplomacy can only do so much. “They also need to invest not just in marginal military alliances. They need to exponentially expand our military, specifically our ammunition stockpiles, and war games,” Sobolik says.

The White House announced July 29 it was using expedited procedures to send $345 million in weapons and military aid to Taiwan. The U.S. has previously approved $19 billion in weapons sales to Taiwan including F-16 fighter jets, anti-ship missiles, mobile rocket systems and hand-held anti-aircraft and anti-tank weapons. Much of that, including Harpoon anti-ship missiles and F-16s, has been delayed because of industrial capacity limits and demands of the war in Ukraine. As covered in Discourse magazine earlier this year, the stark reality is that existing U.S. stockpiles of weapons would be exhausted in a contest with China over Taiwan within five days.

In recent months, the U.S. and what administration officials call “like-minded” nations have reached a wide-ranging set of agreements aimed at maintaining a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and protecting the “rules-based international order.” For instance, in January, after sharply boosting Japan’s defense budget over the next five years, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited Biden in the Oval Office where the two reaffirmed and updated the U.S.-Japan strategic alliance. Prompted by Chinese advances, the U.S. and Japan agreed to work more closely together to counter China and added space as a new domain covered by the United States’ security guarantee of Japan.

In an “increasingly severe security environment,” the U.S. “expressed its determination to optimize its force posture in the Indo-Pacific, including in Japan, by forward-deploying more versatile, resilient, and mobile capabilities.” So, for example, the 12th Marine Regiment which is stationed in Okinawa, will become the 12th Marine Littoral Regiment, a smaller, more nimble force designed for island hopping and anti-ship operations. And late last year, the U.S. Air Force deployed F-22 Raptors to Okinawa to replace an aging fleet of F-15s. Meanwhile, Japan announced it was constructing an airfield and missile base on an uninhabited island in the East China Sea.

In March, U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Australia Prime Minister Anthony Albanese met Biden in San Diego to shake hands on the latest phase of the AUKUS submarine deal. A sweeping strategic agreement initially announced in 2021, AUKUS will provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarines (at first from the U.S. and then Britain) while developing Australia’s indigenous boatbuilding capacity so that the latter can eventually build its own subs. AUKUS also envisions future cooperation on hypersonic missiles and artificial intelligence.

Importantly, the agreement means U.S. and U.K. nuclear submarines will begin regularly visiting Australian ports this year. Australia will make improvements to its western naval port near Perth, allowing U.S. boats to operate for longer time periods in the Pacific without having to return to the United States for routine maintenance. Prime Minister Albanese will visit the White House for a state dinner on October 25 and further discussions on the alliance.

In April, South Korea President Yoon had traveled to Washington for a state visit with Biden. The two announced a new “extended deterrence” plan to address South Korean concerns about the North’s nuclear weapons. In addition to the two countries expanding joint exercises, the nuclear-capable submarine USS Kentucky made a visible call on the port of Busan last month—a demonstration of the United States’ security commitment. It was the first port visit by a U.S. nuclear sub to South Korea since 1981.

The U.S. is also working to bring the Philippines into its coordination with Japan and South Korea. In May, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. visited Biden at the White House to lay plans for security and economic development. This followed a trip by Secretary Austin in February, when he secured the use of four additional bases for U.S. forces for defensive purposes. These visits are evidence of a recent thaw in U.S.-Philippine relations and a reversal of a decline in ties that occurred under Marcos’ predecessor, former President Rodrigo Duterte, who had pursued a more China-friendly foreign policy.

And importantly, in June, Prime Minister Narendra Modi traveled to Washington for a state visit in which China was at the top of the agenda. The U.S. agreed to transfer jet engine technology to India and work with India to strengthen undersea awareness in the Indian Ocean, where Chinese subs have been operating.

“What the administration has done in the last six months has been pretty remarkable in terms of defense posture,” says Zack Cooper, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who studies U.S. strategy in Asia. “They’ve really changed a lot very quickly from Japan to Korea, to the Philippines, Australia, and Papua New Guinea.”

But “whether that’s affecting Chinese decision-making on Taiwan, I’m not so sure,” Cooper warned. “At the end of the day, the Chinese calculus is going to be very focused on the likelihood of the U.S. intervening. So, of course, coalition building matters, but how much does it matter? The jury is still out right now.”

Secretary Austin visited the Pacific island nation of Papua New Guinea in late July to cinch a port deal for the U.S. Navy as part of the broader effort to meet the challenge China now poses in the Pacific. Situated between Australia and the Philippines, Papua New Guinea occupies the eastern-most part of the Indonesian island chain. It was a major U.S. naval hub during World War II.

Now, under a new, 15-year defense cooperation agreement, the U.S. will have “unimpeded access” to the Lombrum Naval Base on Manus Island. It allows the U.S. to pre-position supplies and build infrastructure at the base. In addition, the Coast Guard will send a cutter to help boost Papua New Guinea’s maritime enforcement capacity and American military capabilities.

Of course, military power is only half of the “balance” required to create deterrence, Assistant Secretary of Defense Ely Ratner notes at a CSIS forum in May. By expanding U.S. military alliances in the Pacific, the U.S. does not want to provoke “the type of escalation or crises” that “we’re trying to avoid.” What the U.S. is trying to do is stabilize the region, Ratner says.

In many respects, these steps are updates to the United States’ preexisting, hub-and-spoke system in place since the end of the Cold War. What’s new is a sense of urgency, driven both by China’s assertiveness and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Collectively the United States’ expansion of hard-power cooperation in the Indo-Pacific is an improvement on its posture just a year ago, when U.S. forces in the Pacific were largely confined to legacy bases in Japan and South Korea. Those now are being restructured to address China’s threat to Taiwan, and the number of bases the U.S. military can operate from has been expanded, making China’s calculus more complicated. And the new arrangements invoke more multilateral and trilateral alliances, making the U.S.-led coalition that much stronger, analysts say. It’s also true that much of the military strength envisioned in the new alliances will not come into play for a number of years, or even a decade.

Much is riding on the diplomacy the Biden administration is conducting with Beijing. The administration is preparing for an expected meeting between Xi and Biden during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco in November. Expectations for what can be accomplished are low; possibly some cooperation on fentanyl enforcement and climate measures. Beijing is tying cooperation with Washington to concessions elsewhere from Biden.

“The question everybody is asking is, where are the deliverables,” says Sobolik. Meanwhile, 2027 is not that far in the future. “Our capability shortfall is substantial right now. We are making some good progress. But we’ve got a lot of work to do.”