All Immigrants Are Born on the Fourth of July

A personal take on American exceptionalism

I arrived in the United States as a child from Cuba, and immediately realized things were different here. Nobody talked politics—it was a boring subject. Everyone went calmly about their business and trusted everyone else to do the right thing. Pedestrians walked in front of moving cars because of some abstract notion called the “right of way”! (I still can’t bring myself to do that.) The rules of social life were understood and internalized. Beyond that, it was up to you. The American people seemed to have freedom in their bones, in their DNA: so deep that they didn’t even notice.

Is there such a thing as American exceptionalism? When asked that question, Barack Obama once replied, “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect the Brits believe in British exceptionalism, and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.” As often happened with Obama, he was both glib and wrong.

Actually, each country is not exceptional in its own way and doesn’t deserve a little trophy just for being there. The U.S. stands apart. And it isn’t so much who we are that separates us from other nations as the path that brought us here. Each American alive today benefits from an extraordinary history. Call it luck, call it destiny, but those who came before us rose to every challenge in a manner that defied probability and bestowed on us, their heirs, the easygoing freedom of pedestrians who casually face down moving cars.

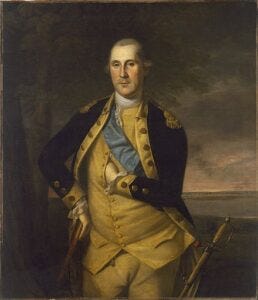

Let’s start at the beginning. In the hands of summer soldiers and sunshine patriots, the Revolution could have gone wrong in many ways. Instead, we got the generation of the Founders and Framers: a world-historical flowering of political genius. These were tough-minded, pragmatic men, who fought and won a war against the greatest power on earth and built a framework of government that has lasted 235 years. But they were also brilliant political thinkers. Their most enduring legacy was an ideology of individual freedom to which even our decadent latter-day politics must refer and yield.

When I asked my five-year-old grandson what he knew about George Washington, all he could say was, “He owned slaves.” That’s how Washington is remembered today: slaves, bad teeth and a face on the dollar bill. But he won the Revolutionary War by sheer force of character; the precedents he set as our first chief executive embodied the ideology of freedom and remain in effect today. Other great men of similar talents behaved quite differently. Napoleon began as first consul then promoted himself to emperor. Simón Bolívar went from liberator to dictator. By contrast, Washington voluntarily and with much relief relinquished power and ended his days as a farmer at Mount Vernon. That was unusual, unlikely—exceptional.

The Civil War could have resulted in nothing more than a brutal power play—the North and the West devouring the South much like Bismarck’s Prussia swallowed the German principalities. That didn’t happen because Abraham Lincoln gave the war a profound moral dimension. The “last best hope” for human freedom, he insisted, was at stake. It was Lincoln who defined our exceptionalism. He believed we were the first nation to rise above the accidents of history and be “dedicated to a proposition.” Yet an ideology of freedom couldn’t coexist with chattel slavery. The slaughter of war was the punishment for that monstrous contradiction. Lincoln’s second inaugural address, a towering moral document, reads like a combination of a Greek tragedy and a lost book from the Bible. He was, to put it mildly, an uncommon politician.

In times of need, other Americans have stepped into the breach with remarkable regularity. When the Great Depression shook our way of life to its foundation, Franklin Roosevelt rejected “fear itself” and restored faith in representative democracy. When the Cold War against the forces of unfreedom appeared eternally deadlocked, Ronald Reagan could only conceive of a single outcome: “We win, they lose”—and so it was.

When the disgrace of Jim Crow segregation needed to be atoned for and eradicated, we should have expected, and certainly deserved, rage and hatred for the oppressors from the Black leadership. Instead, we got a magnificently eloquent preacher who practiced nonviolence and taught Christian forgiveness. As anyone can tell who has read “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King was nobody’s pushover. “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor,” he wrote; “it must be demanded by the oppressed.” But he quoted the words of the Founders in front of the temple to Lincoln in Washington, D.C.—appealing to the American ideology of freedom and demanding a share of it for all Americans. And so began the long process of healing the nation.

Even our industrialists and innovators have been exceptional. Anywhere else, if you wanted to make money you had to sell to the government or to the rich—after all, they possessed most of it. But from Thomas Edison and Henry Ford to Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, American manufacturers aimed their goods at the ordinary citizen, the consumer. (Ford actually kept the prices of his cars low to ensure that “the great multitude” could afford them.) This started a virtuous cycle, since the more money ordinary people made, the more goods they could purchase: Higher salaries for employees actually benefited millionaire CEOs. Here was the ideology of freedom, conquering the economic domain.

And for those of you who love to sneer at “consumerism,” let me repeat a story I have told before. A Cuban woman, a recent refugee, entered a supermarket in Miami and proceeded to burst into tears. Surrounded by such a dazzling display of goods, her heart broke, she said, when she thought of the people she had left behind in Cuba, who had so little.

The opposite of consumerism isn’t authenticity—it’s penury. It’s scarcity and hunger. We are fortunate and exceptional that most of our problems stem from abundance.

This amazing history is the property of every American—and it was the legacy that confronted me when I first arrived in this country. But here’s the strange thing: Fairly quickly, without my knowing how, I started to think of it as my legacy. I internalized the evolution of freedom the U.S. represents. It belonged to me no less than to any Mayflower descendant—maybe more, since I knew too well the alternative to freedom.

My process of Americanization bears thinking on. Having recently tested my ancestry, I know my genetic roots go back almost entirely to Spain and France. So is Thomas Jefferson my “forefather”? Don’t bother to answer—I know he is. He stands in a line with Washington, Lincoln and MLK—and, yes, Edison and Jobs—who, as older family members do, provided for me the maxims and models of how the life of a free citizen should be lived. I have had angry conversations with Jefferson, as I did with my own father; he was an encyclopedic genius but a frustratingly slippery character. Europeans have sometimes asked me why Americans are so obsessed with the opinions of long-dead politicians. My reply is that we have been exceptionally fortunate in our history.

I became American without thinking about it, by osmosis. My personal differences with my native-born friends seemed more like advantages than barriers. Being young in the United States at that time felt like an immense adventure—a constant exploration and discovery of new perspectives in a land of infinite possibilities. Americans, I learned, are restless and lonely, because we always live on the edge of a frontier, and are always tempted to leave everything behind by the siren song of the future. We are, in a word, unsettled. That’s a rare but honorable condition.

At some point, somehow, my life became that of an ordinary American. I went to school, married and begot children, became a bureaucrat at—of all places—the Central Intelligence Agency, moved on to the serial pontification I am engaging in at this moment. My version of the American dream was never extravagant but I have seen most of it come true. Long ago, I found a woman who has put up with me all these years. I have bounced grandkids on my knee and watched the Washington Nationals win the World Series. I never forget that I’m Cuban but weeks go by that I fail to remember I’m an immigrant—if that sounds like a contradiction, you don’t understand the meaning of “Cuban” or the life of an immigrant in the United States.

Some of you, I realize, will object to such talk of freedom and unqualified praise for our country. Half of the American economy was built on slavery, you will say. Well yes, but as Lincoln observed, we paid for that sin with rivers of blood. Still—you will press on—we remained a legally racist country for a century after the Civil War. Well yes, but the Civil Rights Act of 1964 broke the shackles of discrimination and today the highest-earning Americans are of Indian and East Asian descent. But this remains systemically and fundamentally a white supremacist nation, and there’s no help for that, forever and ever, you will charge, unreconciled.

Well no—that’s just fumes inside your head. But if you believe it, then rise to the level of the history that made you. Quit whining. Stop throwing words around and point to cases. Persuade me by engaging in respectful debate, using the shared language of reason and evidence. As so many Americans have done before, become an avatar of freedom in a time of crisis, so that your descendants long hence will look back with pride and say, “That was an exceptional generation.”