A Collage of Everything Imaginable

The work of David Bowie and Jean-Michel Basquiat points the way to the creative world of today and its ever-widening array of choices

I don’t often watch films. But on the rare occasion when I do, I usually go on to watch the film a hundred times. I watch it when I wake up and when I go to bed, and I listen to it as a soundtrack while I’m walking. I float in the film, and it forms the background to daily life. This lasts for weeks, sometimes months.

This year I have watched two films in this way: “Moonage Daydream” and “Basquiat.” Both films are about artists, two artists who knew each other: David Bowie and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Bowie and Basquiat were musicians, actors, writers and painters. Both were addicted to drugs. Basquiat’s drug addiction killed him; Bowie’s almost did. You could make an argument—perhaps an argument that both would have agreed with—that this difference in outcome was a result of their difference in race.

This piece is not about race or drugs. It is not a profile of either artist, or a review of either film. This piece is an attempt to draw out a set of similarities between these two people that, I believe, expands the frame through which we can view them and better understand the nature of creativity today.

Bowie and Basquiat feel of a kind to me because they were collagists to a far greater extent than they were craftsmen. Their work spanned the creative disciplines—one form could not contain their thought. They eschewed heroism, but they became heroes. They collected ideas, characters, moments, and they understood what so few of us still understand about the internet—that it gave us the absurd, godlike ability to record, capture and reuse everything.

Some Painters Paint Heads

Bowie and Basquiat both spent a lot of time living in Manhattan—Soho, in particular. They loved the city, and they hated the city. Neither of them started their lives there, but both of their lives ended there. They were both flirts—Bowie dated Susan Sarandon and Elizabeth Taylor; Basquiat dated Madonna—and they were both painters.

Some painters paint landscapes, and some painters paint heads. Bowie and Basquiat painted heads. Bowie’s heads were varied: self-portraits, friends’ faces, Germans or Turks whose families were divided between East and West Berlin before the fall of the wall. Basquiat’s heads were mostly Black heads—scratched drawings of squalid eyes, square faces and scrawled crowns, with broken words tossed in between—witty, imaginative, indifferent yet afflicted.

When I was in high school, I painted heads too. I spent most of my time in the art department—a light-filled loft full of ramshackle wooden tables, flimsy drawers and seemingly infinite materials—and found myself imitating Basquiat before having ever seen his work. I would print out large images of distorted faces, soldiers, animals—my school had one of those printers that jets out inked paper like a tennis ball machine—and begin to paste them on top of each other, working acrylics and inks into each of them.

In just a few years, Basquiat’s style became recognizable to the point of mimicry, making him a bona fide celebrity. In 2017, almost 30 years after his death, he made headlines when a painting of a black skull, entitled “Untitled,” sold at auction for $110.5 million, making it the sixth-most-expensive piece of art ever purchased.

Bowie’s paintings are entirely unrecognizable. As he put it, “I have no loyalty to style whatsoever. One day I can be a complete minimalist and just paint a stick of wood white, and the next day I want to be florid and painterly.” You can look at a set of Bowie paintings and have no idea they are Bowie paintings. The same was true of his music. There is a Bowie persona—gloriously charismatic, ecstatically androgynous, sporadically moody, delightfully carefree—but over the length of his career, there was no distinctive Bowie sound.

Bowie’s early years were larger than life—literally space age—while his later music was rooted, grounded, centered. He went through several transformations in between, playing everything from arousing ballads to pop anthems to psychedelic jazz riffs and hard rock. He was a dabbler and a flirt in every sense of the word. His life was a continuous act of reinvention. At the very moment he caught himself repeating himself, intuition would tell him to get up and do something radically different.

This is an aspect of Bowie that “Moonage Daydream” captures spectacularly. The film ultimately tells a chronological story, and yet its scenes themselves are not chronological. The experience of watching it means being thrown back and forth in time, one minute on stage with a guitar in front of a thousand adoring fans at Glastonbury, the next minute with to Brian Eno in a studio in Berlin, attempting to create an entirely new “musical language” by chopping up physical pieces of songs and manipulating them based on randomized instructions (a method akin to the one that the Russian writer Anton Chekhov used to arrive at plots for his stories). This process of collage—curating figments of song, language, culture and personality, and remixing them over and over—is perhaps the singular continuous characteristic of Bowie’s work.

In the ’90s, Bowie became mesmerized by the computer because he thought that digital media would upend this collage process and make it accessible to everyone. When he collected other painters’ art—including a set of prized Basquiat pieces—he proceeded to upload copies of each work to a website and asked fans to download the images, manipulate them and re-upload them. This was in 1998. Yet the ironic part about Bowie’s fascination with computers is that computers cannot tell you to do something radically different. Machine intelligence—artificial intelligence—is inherently predictive, drawing from previous work and extrapolating a near-linear trajectory into future work.

A machine could hardly have told Bowie to go from being a practicing Buddhist to a Nietzsche enthusiast within a week. A machine could not have told Bowie to pretend to be an invented character in his interviews. When Bowie was asked to comment about Basquiat’s work, he said that Basquiat “seemed to digest the frenetic flow of passing image and experience, put them through some kind of internal reorganization and dress the canvas with this resultant network of chance.” This element of chance in the creative process is not simply a randomizer in a computer algorithm—it is an equation filtered through the network of an artist’s entire life experience, their entire background.

Basquiat was a collagist too—and not only in his style of painting, but in the background he formed while painting. He painted collage and formed collages around himself as he went about it. One of my favorite scenes in “Basquiat” is a sequence of shots in his basement studio, wooden beams soaring above him as he jumps from canvas to canvas. Basquiat liked to paint multiple canvases at once—one covering the floor, several thrown up against the wall—in rapid bursts of chaos. He would paint with Charlie Parker’s saxophone blazing, a TV flashing old news interviews, and cigarettes intermingled with his brushes—a cacophony of input, all fighting for a place in the composition.

When he was asked to describe his work, Basquiat said he simply did not know how: “it’s like asking Miles Davis to describe how his horn sounds.” The sentiment about one’s own work was echoed by another one of my favorite artists, James Baldwin, who once wrote: “I really do not, at the very bottom of my own mind, compare myself to other writers. I think I really helplessly model myself on jazz musicians and try to write as they sound.” And Bowie said something similar: “The idea of having to say that I’m a musician is an embarrassment to me because I don’t really believe that. I don’t take myself seriously as a musician. I use music for my way of expression.”

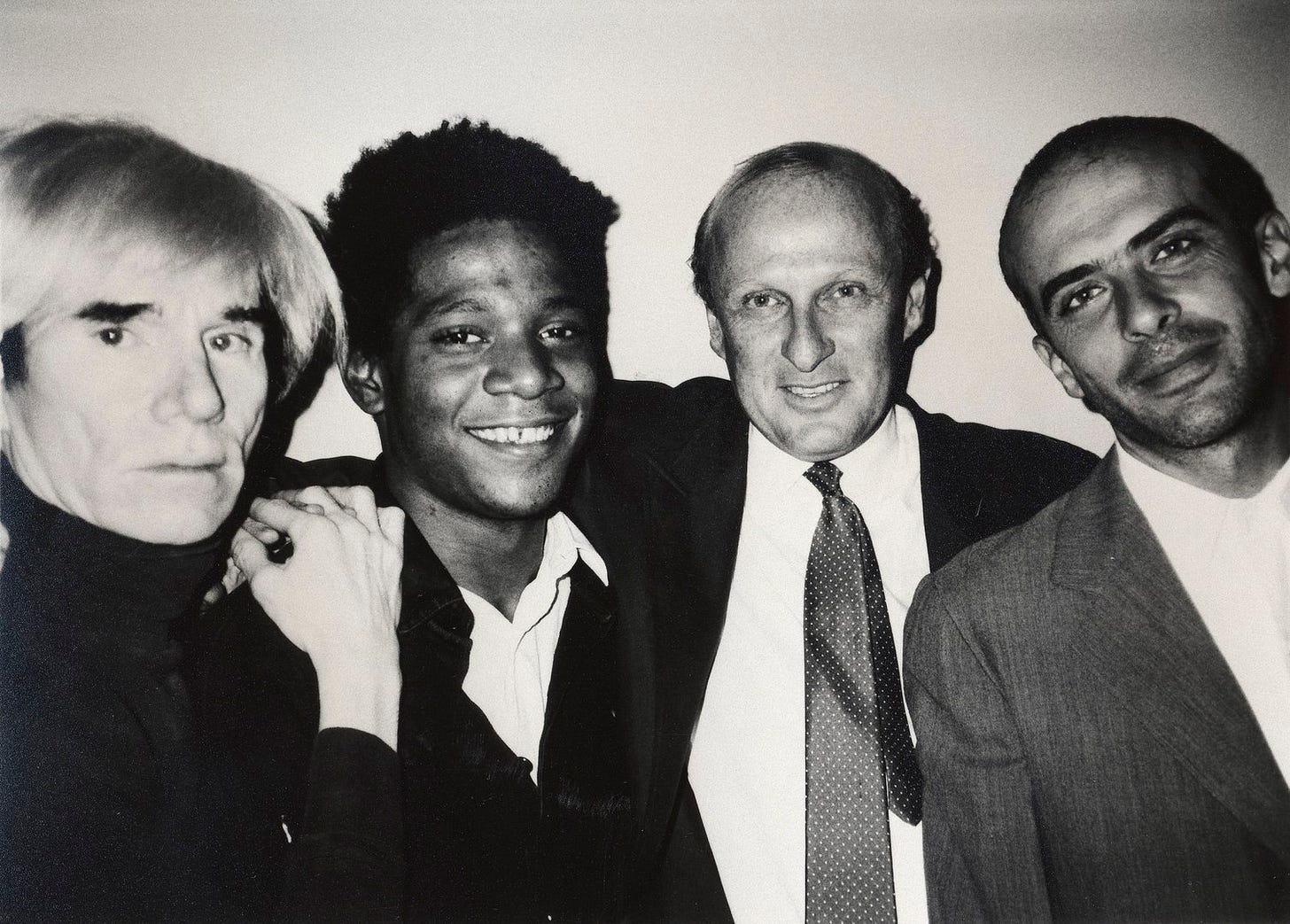

“Basquiat” was the first commercial feature film about a painter made by a painter. It was directed by Julian Schnabel, a contemporary of Basquiat and Bowie, a sort of boisterous, quietly admiring rival—a Norman Mailer of the art world. Basquiat is played sensitively by Jeffrey Wright, alongside quite a remarkable cast that included everyone from Benicio Del Toro, Gary Oldman and Dennis Hopper to Willem Dafoe, Courtney Love, Claire Forlani and Christopher Walken. Bowie stars in the movie, too: He plays Andy Warhol, the enigmatic painter who, depending on whom you ask, is either a symbol of capitalism’s corrosive impact on fine art or the 20th century’s most important visual artist—two views that are not mutually exclusive.

When the film’s Basquiat is painting in his basement studio, he is at his happiest and most fragile. We see him encounter a space of his own for the first time, and his cast of characters, or cast of heroes—Miles Davis, Max Roach, Grandmaster Flash—drifts through the montage on the radio as he throws his body around the canvas, losing himself in the act of creation. But the setting is soon infiltrated by a set of characters looking to profit from his work—agents, fellow painters, snobbish buyers—and old friends from far outside the art world. He leaves in anger and quickly loses himself in self-sabotage, cheating on his girlfriend with a woman he meets on the street.

There is a rage inside Basquiat that hides beneath a quaint, scoffing exterior—I don’t think I have ever seen someone utter a sentence with such anxiety and arrogance at once. The glorious painting scene does not survive, and Basquiat’s life does not last. He dies of a heroin overdose at the age of 27.

Basquiat was also a serious musician. He had a band called Gray, which played in New York at the Tribeca Mudd Club and attempted to deconstruct everything we know about music. Instead of instruments, they focused on sounds and how they could be manipulated—one song revolves around the removal of masking tape from a drum snare, another around the single hit on a triangle.

One of my favorites, “The Mysterious Ashley Bickerton,” is an acid-lounge song that samples an interview between a Parisian radio host, Louise Lazar, and the eponymous visual artist Ashley Bickerton, who sits “on an island, somewhere in the Indian Ocean.” Brian Eno was involved in the formation of this track. It is a collage of eclectic samples, a complete bricolage.

We Are All Collagists Now

Today, every artistic medium is turning into bricolage. The internet has given rise to a new set of forms that make collage the default mode of creation. The artist Fred Gibson, better known as Fred Again—yet another disciple of Eno’s—takes vocal samples, twists them into new forms, and draws them together as part of something with an entirely new identity. In 2019, Gibson began a project titled “Actual Life,” in which he collects samples from various sources—voice memos, clips from YouTube and Instagram, recordings of slam poets and strangers on the London tube—and incorporates them into his own tracks.

Hip-hop artists such as J Dilla and electronic DJs such as Burial adopted this practice decades ago, but Gibson has brought the method to an even broader audience. He has taken over the world of dance music, selling out the largest arenas in the world, working alongside the likes of Ed Sheeran, Skrillex, Stormzy, Four Tet and Stefflon Don.

This is a mode of creation that Bowie and Basquiat embodied, and it is also one that Bowie astutely foresaw. In a 1999 interview with Jeremy Paxman, he spoke about the internet as bringing us to “the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying” in the creative arts.

“It’s just a tool, though, isn’t it?” Paxman asked him. “No, it’s not. It’s an alien life form. Is there life on Mars? Yes, it’s just landed here.”

He went on:

The context and state of content is going to be so different to anything we can envisage at the moment… it’s going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about… The idea that the piece of work is not finished until the audience come to it and add their own interpretation, and what the piece of art is about, is the gray space in the middle. That gray space in the middle is what the 21st century is going to be about.

When Basquiat couldn’t paint, he would play music. When Bowie couldn’t play music, he would paint. Bowie was a musician who saw himself as a painter. Basquiat was a painter who saw himself as a musician. In truth, they were both artists. They were fascinated by the gray space in between. The act of painting is about a collection of choices, the ever-narrowing set of possibilities taken each time a painter makes a mark on the canvas. Making music is about the expansion of choices: You’re in a studio and you catch a riff, you hear a sound, you expand the frame.

Digital art and digital music present the artist with an extreme expansion of choice. If you’re creating a piece of work on a computer, the software can passively record your entire session without you ever having to press the record button. You can make a thousand iterations of one work of art, speeding instruments up and distorting them in ways that the boundaries of physics do not allow, and then retroactively capture your favorite moments.

Generative music, generative art—the state of play when a beat sample or an image need not be found material or a mechanical drawing, but one conjured up by an intelligent algorithm—might turn the person’s role in the creative process into something like an antenna or a transistor: a curator, a taste-maker and a synthesizer in the truest sense of the word. When you can make anything, it’s awfully easy to make nothing, so you must choose how to restrict the tools at your disposal.

Fred Gibson has spoken about needing to switch off 90% of the plug-ins in his music software so as to prevent himself from being overwhelmed by choice. Since the possibilities for recording, distorting and altering are endless, artists must impose constraints upon themselves in order to produce a distinctive work.

In the same way, as image and language models improve and it becomes possible for a machine to create entire songs in a matter of seconds, artists will be defined by their ability to ignore some capacities of the technology, while asking the right questions of the other parts such that they can wield the models for their own individual creative voice.

In an interview about the film “Basquiat” in 1996, Bowie began to rant about the fact that the parameters between the art forms were beginning to break down. He spoke about what it means to apply one’s aesthetic sensibilities and philosophy to each of the different artistic mediums. He drew a straight line from conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp (famous for his iconic use of a urinal more than a century ago to stretch the definition of art) to this modern day creative pose.

This mode is now unprecedentedly important. Our digital powers are quickly making it possible to parody, replicate and predict all variations of art. The act of taking vast amounts of noise and interpreting the signal is what matters. We are becoming less and less constrained by our tools for creation. Given the proliferation of social media, we are not constrained by the distribution of our creations either—all the creative mediums are now distributed on the same global platforms.

As artists, what is constrained is our attention, both as “users” and “providers” of art. The toughest part of the creative process is deciphering how to comprehend that vast expanse of material we now have at our fingertips, both recorded and—in a world of generative AI—imagined.