The Psychopathology of Digital Life

The digital experience has wreaked untold damage, especially upon the young. But all is not lost

A dark midnight of the American soul has descended on us. Together, as a people, we have lost faith in everything and everyone—religion, democracy, science, presidents, doctors, priests. In public, we are consumed with anger and mistrust. In private, we groan under the lash of anxiety and depression. The future fills us with dread. As in a nightmare, we feel we are careening toward some final horror yet we don’t know how to stop the slide. Our condition has no name but might be described as a cross between mass psychosis and an extended existential howl.

The web has been implicated in the rise of the malady. Something about digital life leaves us wounded and sick at heart. Jonathan Haidt, who is probably the keenest observer on this question, compares the experience to the Tower of Babel, with Americans shrieking at one another in mutually incomprehensible tongues. “[I]t’s a story about the fragmentation of everything,” Haidt writes in a recent piece in The Atlantic. Online, we become ghostly copies of true humanity, which, according to L.M. Sacasas, “do not elicit the moral recognition that attends the embodied self” and can be reviled and abused at will.

Other forces are at work. Most pernicious has been the cult of identity and ecology, which lobotomizes our memory and prophesies doomsday for the day after tomorrow. The relationship between identity and the web is tangled but emphatically symbiotic.

I’m looking for an accurate understanding of the American disease in the context of its cultural and digital manifestations. Since the subject is vast, I suggest zooming in on the zoomers—the cohort now entering adulthood—as stand-ins for the whole population. The first generation born with a smart phone in hand should serve as perfect specimens if we wish to study the morbid effects of the digital on the human.

Real-World Effects: The Destruction of the Young

Apple first released the iPhone to the market in June 2007. Suddenly, the digital experience was no longer anchored to a fixed place. It was “mobile”: It pursued us relentlessly and stuck to us like fate itself.

Somewhere in the vicinity of 2010, the mental health of the zoomers began a profound and continuous deterioration. All previous generations, including the self-indulgent boomers and the much-maligned millennials, largely tracked with each other in attitudes and behavior. Such changes as could be observed, like the decline in religious attendance, took place gradually, across decades. The zoomers veered off sharply from this pattern. They were sociological mutants—or else they had been knocked off their orbit by collision with a malignant force.

The following charts, produced by Haidt and a collaborator, Zach Rausch, offer some idea of the suddenness of the collapse:

The portrait that emerges is of a defeated tribe in flight from an implacable enemy, come to the edge of a desolation empty of life or hope. The qualities that characterize the young—love of adventure, exploration, discovery—have frozen into fear. The way ahead contains disasters one can postpone but never escape. Anxiety isn’t a mood disorder—it’s the logical response to an unforgiving environment.

Statistically, the zoomers are the despairing generation. They suffer the world as a place of degradation and shame. Words, they believe, can cause them physical harm; opinions can trigger mental illness. For protection, they have erected a thicket of taboos, anathemas and safe spaces, but this only aggravates the all-consuming anxiety: Since they must police themselves through condemnation and persecution, no space is ever truly safe. They distrust the old, who are tainted by injustice, and they distrust one another, who are prone at any moment to detonate in grievance.

Safety lies in conformity. The young today are herd animals, but the herd has mobbed together at the riverbank and the dark waters teem with predators: There’s no going forward or back. It’s this sense of paralysis, of being locked out of the flow of history, that breeds the despair.

Confusion and dysfunction aren’t the monopoly of youth, however. Of the nearly 200,000 Americans who died of drug overdose in 2020 and 2021, those most at risk were adults aged 35-44, while the largest percentage increase was for adults 65 and over. Even anxiety has spiked on a sliding scale that merely peaks with the young, as this chart, provided by Haidt, indicates:

Ancient societies once sacrificed their children to the gods, that the rest might be preserved from calamity. (The Greek playwrights turned this into high art.) We appear to be trying something similar with our kids. When it comes to the sickness of the age, however, it would be a mistake to think of the zoomers as disposable them—they are us, only more so.

Liminal Panic: The Abolition of Culture

The young inhabit another country. The word “liminal” refers to thresholds: The young by definition are liminal people, having left childhood behind but not yet assumed the duties demanded of every adult. They must stumble about in an ambivalent place, neither here nor there, tormented by doubt, bereft of social rules or institutional guideposts. Anthropologist Victor Turner, who has given us the most lucid account of this state in preliterate societies, describes liminal space as shapeless, indeterminate, “anti-structure.” “Thus, liminality is frequently likened to death, to being in the womb, to invisibility, to darkness, to bisexuality, to the wilderness, and to an eclipse of the sun or moon,” Turner writes.

Those being initiated into adulthood “may be disguised as monsters, wear only a strip of clothing, or even go naked, to demonstrate that as liminal beings they have no status, property, insignia, secular clothing indicating rank or role,” Turner continues. “Their behavior is normally passive or humble; they must obey their instructors implicitly, and accept arbitrary punishment without complaint.”

The threshold is never a destination. The young are “passengers,” crossing out of irresponsibility to the shared burdens of communal living. Every society with a functional culture provides explicit and implicit rites of passage, rituals which can often be terrifying or painful but, once surmounted, as in a second birth, lead the travelers out of liminal space to the structured domain of adult relations. The point is to transmit to a new generation the values and practices specific to a group. A second-level goal is to enable the young to shed their doubts and fears and navigate successfully the complexities of social life.

But what if the culture is loathsome and its keepers command that it be uprooted, down to the last “thou shalt”? Worse yet, what if the young are told that there’s no help for it—their way of life is mathematically certain to destroy the earth within a few years? That’s precisely the message preached by the cult of identity and ecology. Its prophets hold that history must be repudiated rather than understood. The ruling culture must be abandoned rather than internalized. An obsession with race and sex must trump inherited values like equality and tolerance. And regardless of what we do, it’s too late. The climate apocalypse is now.

Zoomers in large numbers have forsaken the religions of their ancestors to genuflect before the sterile altar of the cult. They have toppled the statues of the old saints but have nothing to put in their place. Because they wish to do the right thing, because they fear contamination from a hateful past, they aim to rip themselves out of their own culture—but this means they have lost the way to safe harbor, and are left with nowhere to go and no one to be. Millions of young and not-so-young people are stuck in the shifting shadows of liminal space.

Fluidity of identity and sexuality are liminal states. So are an inability to marry and to reproduce. So is passivity in the face of arbitrary punishment from identity fanatics. The anxiety, the depression, the horrible increase in attempted and successful suicides—all are liminal moves, traumatic reactions to the approaching world of structure. Every aspect of maturity, from driving a car to having sex, the zoomers have handled uneasily and late. That makes perfect sense if growing up means being devoured by Moloch.

The obliteration of a culture by those who belong to it is a little like a snake swallowing its own tail. There’s nothing left at the end. Oppressed by the doctrines of a nihilistic faith, a generation has clung to the threshold as to a sanctuary, to protect their innocence by avoiding the crimes of pollution or patricide. Liminality exists outside history—it’s said to resemble both death and the womb. The fatal despair of the zoomers is rooted in the fear that they might grow old and perish without ever being born.

Since identity has become the established church of American institutions, the rest of us, no matter how antiquated or ornery, are in the same boat. By the dictates of the church, we are allowed to be either victims or villains. Victimhood is a return to liminality. Being condemned to the villain class has driven adults to liminal behavior like drug and alcohol abuse. No other choices are on offer—no way forward or back. All the while, we are expected to watch passively as the young ones, disguised as monsters, bring down the temple on their own heads.

Lost in the Web: The Mutilation of the Self

The cult of identity has spread like a debilitating virus along vectors predetermined by the digital environment. In fact, identity is exactly the kind of jumble of dogmatic negations one would expect to arise from the web—little different, in this respect, from the anti-government Yellow Vests of France or the anti-“system” indignados of Spain. Like every web-inspired movement, the cult disdains coherent ideological positions and programmatic thinking but offers an endless supply of slogans, memes and emotive images. In a disembodied medium, it has exalted the magical power of the word, and it polices verbal purity with internet mobs that fling denunciations in the manner of stones at the offender.

It’s fair to wonder why the frightfully well-meaning zoomers have embraced such a delusional and destructive creed. We could just as well ask why ordinary middle-class Americans would swallow, even unto death, the poisonous gibberish spouted by QAnon. These are people who seek the good and the true but are lost in a house of mirrors. The zoomers average 10.6 hours online per day; most of that time is spent alone. The nightmarish culture painted by the preachers of identity corresponds pretty closely to the lived experience of the young.

Research has quite naturally focused on the real-world effects of overdosing on digital. Few have tried to understand the mutilations forced on us as an entry cost by the medium: what we become when we plunge online. Sacasas is a notable exception—and while he was undoubtedly right to warn about a loss of “moral recognition,” the distortion and diminution of our human faculties run much deeper than that.

On entering the digital realm, we are swept along a formless tide of signs, symbols, half-meanings, claims and counterclaims, potent desires impossible to satisfy—a place where everything is true yet nothing is, and there’s no way to test the question. Identity melts into flux, and we come face to face with our own strangeness, our lack of substance, our terrifying inscrutability and distance from one another. To cross that gulf somehow becomes the chief organizing principle of a wholly disorganized personality.

The digital self is flat, ahistorical, decontextualized, and it is born, like every infant, with a grasping instinct, a frantic need to clutch someone or something. This can lead to genuine connection but more frequently results in the opposite. The hunger for community sours into mob behavior. The need for certainty ends in inquisition and taboo. The search for meaning is perverted by false prophets thundering the secret names of the supervillains who are to blame for all our failings. Obsessed with its own insubstantiality, the digital self clings to narcissism as a survival strategy. The image on the selfie is proof that one exists.

Anxiety and despair, twin masters of the age, get transmuted online into a horrific scramble for personal attention that resembles nothing so much as self-worship and will to power. Those who attend to me sustain, for an instant, my disintegrating self: The “social” feels mostly vampirical. Outwardly, the web may appear to be the ultimate threshold, but the drama inside plays out over minute shadings of status in a vicious anti-liminal space. We arrive laden with titles: poster, user, commenter, follower, friend. But we “engage”—the word connotes combat—to secure some portion of existence through social supremacy, and we dream of rising to the heights of a digital warlord like Donald Trump or, even more ambitiously, to enter the Olympus of the “influencers.”

The real-world effects, as we have seen, are traumatic but unintended, wholly detached from the noise inside the box. Online dramas, like online persons, lack substance. If we understand pornography to be the triumph of the wish over the deed, the bulk of our performance in the digital theater must be classified as pornographic.

That the cult of identity, which wages war over pronouns, should attain epidemic proportions within this circle of fantasies seems almost inevitable, at least in the wisdom of hindsight. That identity and the web, coiled parasitically around the beating heart of our culture, are together responsible for zoomer peculiarities and most of the symptoms of the American disease, I take for granted. The big question left hanging is whether there’s anything to be done for it.

Real Versus Virtual: The Quest for Immunity

In line with the prevailing mood, attempts to manage the American disease have been moralistic and nostalgic. Under the banner of truth and science, our institutional elites have tried to seize control of the information sphere and in this way return us to the glorious hierarchies of the 20th century. On the other side of the cultural divide, a rebellious public, led by politicians like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, seeks to mandate by law what was ostensibly “normal” in the golden past. These maneuvers strike me as exercises in futility. Precisely because the hierarchies have fractured irretrievably, there can be no going back to the old normal.

Moral anxiety is the unhappy offspring of a profound structural dislocation: For two decades, the digital storm has pounded away at the landscape, leaving it shattered and unrecognizable to many of our ideals and customs. That’s the starting point, whether we like it or not. Repression of the information system isn’t a realistic alternative unless we adopt North Korean methods. To cure the American disease, we’ll have to learn to live with the web.

The first order of business is to rescue the millions of kids buried alive in liminal space. Those who murmur “Anything goes” strike the pose of liberators but in truth are abandoning the young to eternal confusion. The essential element is structure—clear and specific rules about what it means to be a functional adult, a man or a woman, a neighbor and a friend. Mastering structure—coming to terms with social reality—must be the goal of new-model rites of passage that will prompt young people out of Neverland into the tumult of history.

And this must be done within the framework of the digital experience, which means that the old, who are normally the keepers of the rules, are useless for the job. I grew up in a time in which a young man picked up the phone and, trembling with trepidation, called a young woman to ask for a date. I can have no moral authority in an era of algorithmic romance. We Old Ones can push, assist and applaud, but a double burden falls on the zoomers: They alone can design the bridge that will take them to adulthood.

We must disestablish the cult of identity. Our fellow citizens should be free to believe in any nonsense they wish, including the reality of pregnant fathers and a Hitlerite America—but the rest of us, who are a large majority, must not be compelled to worship at the same pew by threats or bribes from government at any level, places of employment or billionaires with a bad conscience like Bill Gates or George Soros. A prolonged civil rights struggle confronts us, with the 2024 election the first significant battleground. A major objective will be to reconfigure the web into a means of inquiry rather than inquisition.

The most urgent task is cultural. We must challenge our finest imaginative spirits to nothing less than a second birth of American culture, in which the American experience, for all its loneliness and violence, and all the hours spent online, is portrayed the way it is and always has been: as a rush to the frontier and a humanizing adventure. The central character of movies and television series, songs and memes, will be the pioneer and the true eccentric instead of the thug and the designated victim. The web already is an incubator of artistic genius—it should be the battering ram to break culture free from the dead hand of Hollywood and Silicon Valley.

Many experiments will be conducted on the road to immunity. Balaji Srinivasan, for one, proposes to cure the digital with more digital, by erecting the “Network State” based on blockchain-enabled association. Srinivasan’s utopian vision is so bracing one is left gasping for air, but he may be right to bet on blockchain technology to resolve “moral issues” like information manipulation and restore an “in-person level of civility” to online exchanges.

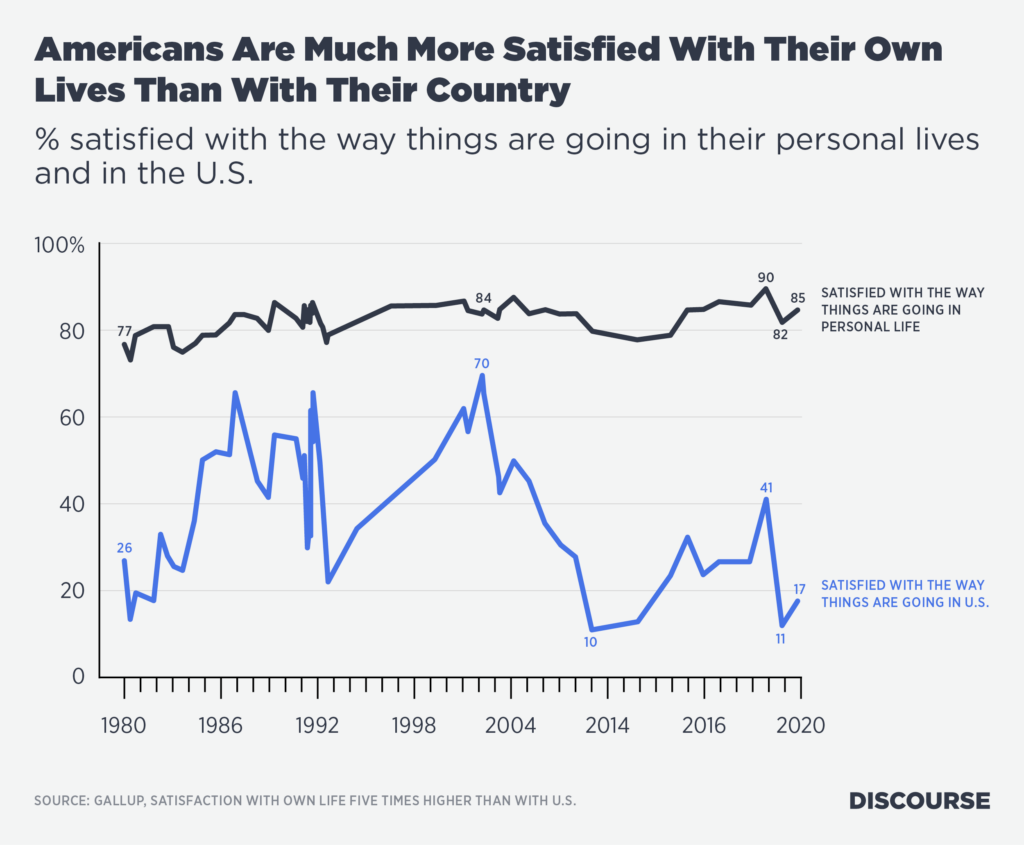

I’d be content if we just got out of the pornography business—if a healthier balance could be struck between fantasy and desire on one side and material existence on the other. The prospect is less improbable than one might imagine. Here for example, is a comparison of how Americans assess their personal situation with how they feel about the shape of the country as a whole:

In a way, this is the most troubling data point of all. If each of us is fine but all of us are sick, a massive warping effect is evidently at work. The digital isn’t an alternate reality but a distortion of the only reality we have. If, like the zoomers, you don’t distinguish between virtual and real, the “I’m all right” line at the top of the chart will plummet toward the apocalyptic line below.

But there is a distinction. I can easily raise my eyes from the turmoil in my laptop to look through a window at my neighbors passing by—jogging, biking, ambling along with their children and their dogs. They seem serene and free. By any historical standard, we are the privileged children of a tolerant and bountiful civilization. That’s how to read the top line of the chart. Only in the subjective dreamlands enabled by the web do we turn fearful of doomsday and enraged with one another.

The human, I believe, can overcome the digital. Our physical selves can seize control over the morally mutilated beings we have become online. To get there, we’ll have recourse to a nearly forgotten virtue: courage. We will learn to stand alone. When called for, we will walk against the herd. Facing the fury of the internet mob, the enormous pressure to conform, and above all our own anxiety and despair, we will remember the words with which John Paul II confounded a totalitarian empire: “Be not afraid.”